Buddhism can be understood on many different levels. People who actualize the Buddhist path do so gradually. Just as you pass slowly through school and university, graduating from one year to the next, so do Buddhist practitioners proceed step by step along the path to enlightenment. In Buddhism, however, we’re talking about different levels of mind; here, higher and lower refer to spiritual progress.

In the West, there’s a tendency to consider Buddhism as a religion in the Western sense of the term. This is a misconception. Buddhism is completely open; we can talk about anything. Buddhism has its doctrine and philosophy, but it also encourages scientific experimentation, both inner and outer. Don’t think of Buddhism as some kind of narrow, closed-minded belief system. It isn’t. Buddhist doctrine is not an historical fabrication derived through imagination and mental speculation, but an accurate psychological explanation of the actual nature of the mind.

When you look at the outside world you have a very strong impression of its substantiality. You probably don’t realize that that strong impression is merely your own mind’s interpretation of what it sees. You think that the strong, solid reality really exists outside, and perhaps, when you look within, you feel empty. This is also a misconception: the strong impression that the world appears to truly exist outside of you is actually projected by your own mind. Everything you experience—feelings, sensations, shapes and colors—comes from your mind.

Whether you get up one morning with a foggy mind and the world around you appears to be dark and foggy, or you awaken with a clear mind and your world seems beautiful and light, understand that these different impressions are coming from your own mind rather than from changes in the external environment. Instead of misinterpreting whatever you experience in life through wrong conceptions, realize that it’s not outer reality, but only mind.

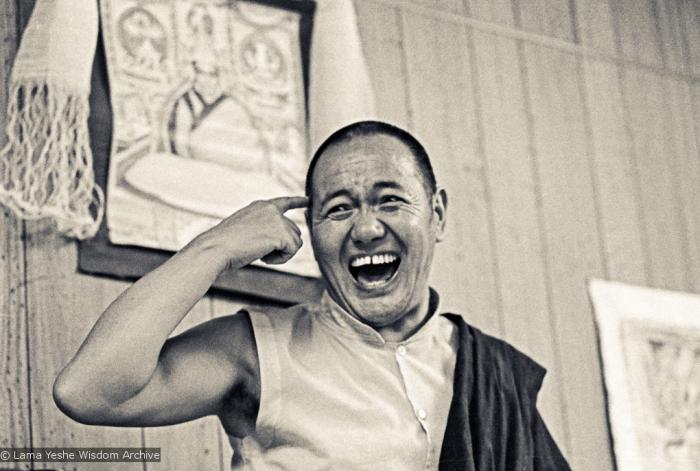

For example, when everybody in this auditorium looks at a single object—me, Lama Yeshe—each of you has a distinctly different experience, even though simultaneously you are all looking at the one thing. These different experiences don’t come from me; they come from your own minds. Perhaps you’re thinking, “Oh, how can he say that? We all see the same face, the same body, the same clothes,” but that’s just a superficial interpretation. Check deeper. You’ll see that the way you perceive me, the way you feel, is individual, and that at that level, you’re all different. These various perceptions do not come from me but from your own minds. That’s the point I’m making.

Then the thought might arise, “Oh, he’s just a lama; all he knows about is mind. He doesn’t know about powerful scientific advances like satellites and other sophisticated technology. There’s no way you can say that those things come from mind.” But you check up. When I say “satellite,” you have a mental image of the object that you’ve been told is a satellite. When the first satellite was made, its inventor said, “I’ve made this thing that orbits the earth; it’s called a ‘satellite.’” Then when everybody else saw it, they thought, “Ah, that’s a satellite.” But “satellite” is just a name, isn’t it?

Before the inventor of the satellite actually made it, he speculated and visualized it in his mind. On the basis of this image, he acted to materialize his creation. Then he told everyone, “This is a satellite.” So everyone thought, “Wow, a satellite; how beautiful, how wonderful.” That shows how ridiculous we are. People give things names and we grasp at the name, believing it to be the real thing. It’s the same thing no matter what colors and forms we grasp at. You check up.

If you can understand what I’m explaining here, you’ll see that indeed, satellites and so forth do come from the mind, and that without mind, there is not a single manifest material existence in the entire sense world. What exists without mind? Look at all the stuff you find in supermarkets: so many names, so many foods, so many different things. First people made it all up—this name, that name, this, this, this—so then, this, that, this, this and this all appear to you. If all these thousands of supermarket items as well as jets, rockets and satellites are manifestations of mind, what then does not come from mind?

If you check into how your mind expresses itself, your various views and feelings, your imagination, you will realize that all your emotions, the way you live your life, the way you relate to others, all come from your own mind. If you don’t understand how your mind works, you’re going to continue having negative experiences like anger and depression. Why do I call a depressed mind negative? Because a depressed mind doesn’t understand how it works. A mind without understanding is negative. A negative mind brings you down because all its reactions are polluted. A mind with understanding functions clearly. A clear mind is a positive mind.

Any emotional problem you experience arises because of the way your mind functions; your basic problem lies in the way you misidentify yourself. Do you normally hold yourself in low esteem, see yourself as a poor quality human being, while what you really want is for your life to be of the highest quality, to be perfect? You don’t want to be a poor quality human being, do you? To correct your view and become a better person, you don’t need to squeeze yourself or to jump from your own culture into another. All you need to do is to understand your true nature, the way you already are. That’s all. It’s so simple.

What I’m talking about here is not Tibetan culture, some Eastern trip. I’m talking about your trip. Actually, it doesn’t matter whose trip I’m talking about; we’re all basically the same. How are we different? We all have mind; we all perceive things through our senses; we are all equal in wanting to enjoy the sense world; and equally we all grasp at the sense world, knowing neither the reality of our inner world nor that of the outer one. There’s no difference, whether you have long hair or short, whether you’re black, white or red, no matter what clothes you wear. We’re all the same. Why? Because the human mind is like an ocean and we’re very similar to each other in the way we’ve evolved on this earth.

Superficial observation of the sense world might lead you to believe that people’s problems are different, but if you check more deeply, you will see that fundamentally, they are the same. What makes people’s problems appear unique is their different interpretation of their experiences.

This way of checking reality is not necessarily a spiritual exercise. You neither have to believe nor deny that you have a mind—all you have to do is observe how it functions and how you act, and not obsess too much about the world around you.

Lord Buddha never put much emphasis on belief. Instead, he exhorted us to investigate and try to understand the reality of our own being. He never stressed that we had to know what he was, what a buddha is. All he wanted was for us to understand our own nature. Isn’t that so simple? You don’t have to believe in anything. Simply by making the right effort, you understand things through your own experience, and gradually develop all realizations.

But perhaps you have a question: what about mountains, trees and oceans? How can they come from the mind? I’m going to ask you: what is the nature of a mountain? What is the nature of an ocean? Do things necessarily exist as you see them? When you look at mountains and oceans, they appear to your superficial view as mountains and oceans. But their nature is actually something else. If a hundred people look at a mountain at the same time, they all see different aspects, different colors, different features. Then whose view of the mountain is correct? If you can answer that, you can reply to your own question.

In conclusion, I’m saying that your everyday, superficial view of the sense world does not reflect its true reality. The way you interpret Melbourne, your imagination of how Melbourne exists, has nothing whatsoever to do with the reality of Melbourne—even though you might have been born in Melbourne and have spent your entire up and down life in Melbourne. Check up.

In saying all this, I’m not making a definitive statement but rather offering you a suggestion of how to look at things afresh. I’m not trying to push my own ideas onto you. All I’m doing is recommending that you set aside your usual sluggish mind, which simply takes what it sees at face value, and check with a different mind, a fresh mind.

Most of the decisions that your mind has been making from the time you were born—”This is right; this is wrong; this is not reality”—have been misconceptions. A mind possessed by misconceptions is an uncertain mind, never sure of anything. A small change in the external conditions and it freaks out; even small things make it crazy. If you could only see the whole picture, you’d see how silly this was. But we don’t see totality; totality is too big for us.

The wise mind—knowledge-wisdom, or universal consciousness—is never fazed by small things. Seeing totality, it never pays attention to minutiae. Some energy coming from here clashing with some other energy from there never upsets the wise because they expect things like that to happen; it’s in their nature. If you have the misconception that your life will be perfect, you will always be shocked by its up and down nature. If you expect your life to be up and down, your mind will be much more peaceful. What in the external world is perfect? Nothing. So since the energy of your mind and body are inextricably bound up with the external world, how can you expect your life to go perfectly? You can’t.

Thank you so much. I hope you’ve understood what I’ve been saying and that I have not created more wrong conceptions. We have to finish now. Thank you.

Latrobe University, Melbourne, Australia, 27 March 1975