Next you have to generate yourself as Chenrezig, which is the actual body of the meditation. You can’t generate yourself as Chenrezig without having first received a great initiation. Otherwise, it becomes revealing secrets. Even if you haven’t received a Chenrezig great initiation, if you have received a Highest Yoga Tantra initiation you can visualize yourself as Chenrezig.

Meditating on the six deities is the most important practice of Action Tantra, and the first of them is meditating on the ultimate deity, or the deity of absolute nature. Until you have received a great initiation, you can just meditate on the emptiness of the I, the deity Chenrezig and all other phenomena.

1. The Ultimate Deity

If you have already had some experience of emptiness, this meditation is easy. Instantly recall that experience of emptiness and think, “This is the absolute nature of Chenrezig,” and meditate on that. This is not exactly the same as the dharmakaya meditation in Highest Yoga Tantra, with its four characteristics, but I think it could be a substitute for that. It doesn’t have all the qualities of the dharmakaya meditation.

If you haven’t experienced emptiness, you can’t suddenly see emptiness, or absolute nature.

OM SVABHAVA SHUDDHA SARVA DHARMA SVABHAVA SHUDDHO HAM

Myself, the meditational deity and all phenomena become of one taste in emptiness.

When you meditate on the ultimate deity, the natures of you, the meditational object (the deity) and all dharmas (all things and events) become of the same essence, the same taste, in emptiness, like having put a drop of water into the ocean. When many streams come from different directions to mix in the ocean, there is nothing to differentiate them. It is like that with the emptiness of all these things: everything becomes of one taste.

If you don’t get much feeling from this, think that this I, the meditator, is merely imputed to its base, the aggregates. Therefore, this I is empty; it doesn’t exist from its own side. What appears to exist from its own side is empty from its own side.

Stop there and meditate for a little while.

A brief meditation on emptiness

As beginners, we haven’t had any experience of emptiness; we haven’t even recognized the object to be refuted. To get some idea of emptiness, first of all we have to get some idea of what it is that we have to see as empty. In order to recognize the emptiness of the I, we have to know about the object to be refuted, the thing that we have to see as empty. We have to recognize that the object to be refuted, which is on the I, doesn’t exist.

One simple way to recognize the object to be refuted is to meditate in the following way. First of all think, “The I is merely labeled.” Remember the base on which you label “I”: the five aggregates, the association of the body and the mind. Try to have the aggregates on which you label “I” become the object of your mind. Then think, “My mind has merely labeled ‘I’ on this. There is no I existing on this at all, except the I that has been merely labeled by my mind.”

It is good to take your time in thinking about this.

Then check the result in your mind. Is there any change in your experience when you think this? When you hear and think of the meaning of the word except, it becomes very clear that not the slightest I exists from its own side on these aggregates. It is very good if you experience this as it means you have either already been able to recognize the object to be refuted or will soon be able to do so.

A more elaborate meditation on emptiness

I will now explain a more elaborate way to meditate on emptiness. If you don’t recognize what doesn’t exist, there’s no way you can meditate on emptiness. You first have to recognize what exists and what doesn’t exist. To really know how the I exists you have to know the I that doesn’t exist. It is only by realizing the emptiness of the I that you can realize how the I exists. Before realizing the emptiness of the I, you have no way of realizing how the I exists.

The association of the body and the mind comprise what are called the aggregates. There are five aggregates: form; feeling; discrimination, or recognition; the compounding aggregates; and consciousness. First of all, we need to know the definition of the I, the person, the being. What is the definition of the I? What are the characteristics of the I? The I is that which is merely imputed in dependence upon the base, one of the five aggregates. As human beings, we have all five aggregates, but beings in the formless realm don’t have a body, a form, and have only consciousness. To include beings in the formless realm, the general definition mentions one of the five aggregates. For us, however, the I is merely imputed in dependence upon the base, the group of all five aggregates.

So, the I is that which is merely imputed in dependence upon the base, the group of the five aggregates or one of the five aggregates. That is what the I is. From this definition it is clear that the mind is not the I, the body is not the I, each of the five aggregates is not the I and even all five aggregates together are not the I. There is no I anywhere on these aggregates.

Nothing of this is the I. Neither the body nor the mind is the I; none of the five aggregates is the I and even the whole group of the aggregates is not the I. The I is neither inside the body nor outside it. The reality is that you can’t find the I anywhere on this base, but that doesn’t mean that there’s no I, that the I doesn’t exist. There is I. As mentioned in the definition, the I is that which is merely imputed in dependence upon the base, the five aggregates or one of the five aggregates. Even though we may think that the body is the I or the mind is the I or even the association of the body and mind is the I, that is completely wrong.

The I exists, but what is it? The I exists, but it exists as a mere imputation by the mind. What the I is is extremely subtle, extremely fine. Compared to our previous belief in a real I, the I that appears to us and we hold to be true, it’s like the I doesn’t exist. It’s not that it doesn’t exist, but it’s like it doesn’t exist compared to that other real I. It’s not nonexistent but it’s like it doesn’t exist. Saying the word “like” makes a huge difference. You can’t say that the I doesn’t exist, but what exists is unbelievably subtle.

It is just because the aggregates, and basically the consciousness, are here now in this room that the mind has merely labeled, or imputed, “I am here in this room,” and believed in that. That’s all it is—just an idea.

Even though this is what the I is, we think the I is completely something else. Day and night we think the I is here inside our body, somewhere inside our chest. We think we can find a real I inside our chest, where there is no I at all. Our normal belief that the I exists inside our body is a complete hallucination. Our thinking there is an I where there is no I is like believing we have a million dollars in our hand right now. It’s a complete hallucination. How we normally think of the I has nothing to do with the reality of the I. The reality is something else completely.

Even though the I is merely labeled, it doesn’t appear to us that way. It appears to be independent, unlabeled, real from its own side. It is the same with a mala. When we look at a mala, it appears to be a real mala. Even though the mala is merely labeled by our mind, it doesn’t appear that way. It appears to be something independent, unlabeled, real from its own side. We label this object “mala” in dependence upon its shape and function. Our mind merely imputes “mala,” but it doesn’t appear that way to us. The mala we have merely labeled appears to us in the wrong way, as an independent mala, an unlabeled mala, a real mala from its own side. Again, that real mala from its own side doesn’t exist; it’s empty, completely empty, just like the I. The real I from its own side that you feel is inside your chest is also completely empty.

When you are sitting on a cushion on the floor, there’s a cushion from its own side and a floor from its own side. Again, in reality, our mind merely imputes “cushion” and “floor.” But where you are now sitting and where you are going to do prostrations don’t appear that way. An unlabeled, independent, solid, concrete cushion and floor appear to you. Again, they are completely empty from their own side.

The real I doing prostrations and doing Chenrezig retreat, the real body, the real mala, the real floor and the real room are like things in a dream. While you are awake, you don’t call what you are experiencing dreaming, but it’s like a waking dream. When you are asleep, the things in your dreams don’t exist. There are also daytime dreams when you are awake. All these daytime dreams are hallucinations. If you label these real things as dreams, it’s very helpful for meditation on emptiness. When you think this real I, this real body, this real mala, this real floor and this real room are all things in a dream, you then know that it means that even though they appear to be real, they’re not real; they don’t exist in that way in reality.

When you think all these things are like things in a dream, it means that they’re not true, that they don’t exist. These real things do not exist from their own side. That is the ultimate nature of things. You then concentrate on this ultimate nature, this emptiness, for a little while, without allowing your mind to become distracted.

(I can’t explain exactly what you meditate on at this point because it has to do with tantric meditation, but what I have just explained is the foundation for meditating on emptiness.)

Meditating on the ultimate deity

Think, “During beginningless rebirths until now, my mistake has been believing that the I exists—in other words, that there is a truly existent I, a real I. The way I have believed the I to exist is actually a complete hallucination. That real I, that truly existent I, doesn’t exist. In reality, the real I is completely false, completely empty.”

Just focus on that.

“In emptiness, there’s no such thing as subject, action, object. There’s no me, no deity, no phenomena. There are no such things.”

“Everything is of one taste in emptiness. In emptiness there’s no such thing as, ‘This is my emptiness and this is the deity’s emptiness.’ It’s of one taste, like having put a drop of water into the ocean.”

This way of meditating on the absolute deity is like an atomic bomb, the weapon that gives the greatest, quickest harm. You then do the meditations on the rest of the six deities by continuing this awareness of emptiness.

2. The Deity of Sound

This emptiness now manifests in the sound of OM MANI PADME HUM, which pervades the whole of space. This is the deity of sound.

3. The Deity of Syllables

Your mind, the inseparable absolute nature of yourself and the deity, becomes a moon disc. The mantra in space is decorated around the moon disc as if the syllables have been written with pure liquid golden sounds.

The moon disc and the sound of the mantra are actually both manifestations of your absolute nature, which is oneness with the absolute nature of Chenrezig. First you think of the sound. Afterwards, when you’ve transformed the moon disc, the sound appears actualized in the letters decorated around the moon.

Concentrate on this, which is the deity of syllables.

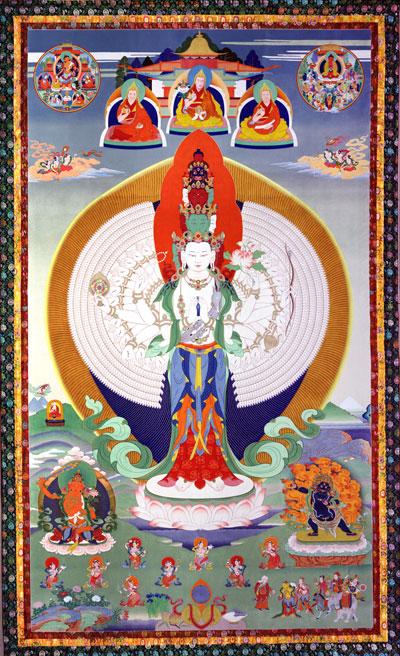

4. The Deity of Form

The peaceful red face on the crown is that of Amitabha, signifying that Chenrezig became enlightened in the essence of Guru Amitabha. Having Amitabha on his crown means that even after having achieved enlightenment, Chenrezig still respects and prostrates to Amitabha, to the guru.

When time is short, instead of going over all the details of the aspect, you can abbreviate the description of the aspect to “Chenrezig with a thousand arms and a thousand eyes.” Other parts of the practice can also be abbreviated when you want to do it quickly.97

5. The Deity of Mudra

After you become Thousand-Arm Chenrezig, there is the deity of mudra, in which you bless the five places with the commitment mudra and OM PADMA UDBHAVAYE SVAHA. With your hands in the mudra of the lotus family, first touch your heart, then the point between your eyebrows, your throat and then your two shoulders.

6. The Deity of Sign

The last of the six deities is the deity of sign. Meditate here on the meaning of the transcendental wisdom of nondual clarity and profundity.

First invoke the transcendental wisdom beings and then the empowering deities. After finishing the initiation, visualize the transcendental wisdom being at your heart.

Focusing your mind and meditating on yourself clarified in the holy body of the deity without being distracted is meditation on the deity of sign. There are two ways of doing this. One way is to go through the details of the aspect one by one. After doing that analytical meditation, then do fixed meditation, one-pointedly concentrating on the general view of yourself generated as Thousand-Arm Chenrezig.

The way to stabilize single-pointed concentration on yourself as Chenrezig is not to let the wind go out through the pores of your body but to keep it inside so that there’s no air going out. Block the air coming in and out. Since the wind doesn’t go out through the pores, the mind, which rides on the wind, doesn’t go out, and your single-pointed focus on yourself as the deity will last longer. Try to have clear meditation with intense remembrance and awareness that you are Chenrezig. You have to stop sinking thought and attachment-scattering thought from arising. Hold the strong divine pride, “I am actually Chenrezig. This Chenrezig I have clarified is me.”

Keep the air inside, without letting it go out. Keeping the wind inside by thinking that you have closed your pores helps your mind not to wander. Think, “This pure base, this pure body and mind clarified as Chenrezig, is my result-time Chenrezig, with a thousand arms and a thousand eyes. This pure base to which ‘Chenrezig’ is merely imputed is not somebody else—this is me. I am Chenrezig.”

Hold the strong divine pride, “I am Chenrezig,” combined with the clear appearance of yourself as Chenrezig. Unify these two.

You have the intense divine pride that you actually are Chenrezig combined with the clear appearance of yourself as Chenrezig. However, even though this divine pride appears as if it exists from its own side, it’s actually merely imputed to the base by thought. It is empty. As well, the Chenrezig that appears to exist from its own side is empty from its own side. It is merely imputed to this pure base. Your previous impure aggregates became empty; then, out of emptiness, pure aggregates with one thousand arms and one thousand eyes were generated. There is a combination of wisdom and appearance, which means Chenrezig’s holy body. Think, “I, Chenrezig, am merely imputed.” It is like the reflection of your face in a mirror: even though the reflection appears as a face, it’s empty of being a face. There’s an appearance of a face, but it is not a face. There’s an appearance, but it’s empty.

Meditate on Chenrezig with this divine pride, but with no clinging to a truly existent I, a truly existent Chenrezig. Meditate on Chenrezig in the meaning of vajra, the unification of method and wisdom, of clarity and profundity. This is the transcendental wisdom of nondual clarity and profundity, the very essence of the meditation of lower tantra.

There is Chenrezig on this pure base, but there’s no Chenrezig from its own side. There is unification of the absolute truth and the conventional truth. Chenrezig is empty of existing from its own side, but it’s a dependent arising, merely imputed to its base. So, it unifies the two truths.

The way you hold the strong divine pride of yourself as Chenrezig, as well as your focus on Chenrezig, is like seeing a mirage. Even though water appears to your eyes, at the same time you know that there is no water there. In the same way, even though Chenrezig appears from its own side, you know there is no Chenrezig from its own side. Chenrezig is merely imputed to this pure base, and it appears to the wisdom that is aware of absolute nature that Chenrezig is empty from its own side. This is the yoga of nondual clarity and profundity. Your mind focusing and meditating on the aspect of yourself as Chenrezig is the clarity. That same mind is aware that while there is no Chenrezig from its own side on this base, there is a merely labeled Chenrezig on this base. That same mind being aware that Chenrezig is a dependent arising and is empty of existing from its own side is the profundity.

That one mind is creating the cause of dharmakaya and rupakaya together. The mind focusing on the aspect of Chenrezig is method, and that same mind being aware of the absolute nature, that it’s empty of existing from its own side, is wisdom. Profundity, the awareness of emptiness, is the cause of dharmakaya, and clarity, the clear appearance of Chenrezig that the wisdom is focusing on, is the cause of rupakaya. This meditation accumulates both the merit of wisdom and the merit of method, enabling you to achieve the unification of dharmakaya and rupakaya, or enlightenment. This meditation makes enlightenment happen quickly on your mental continuum.

Whenever you meditate on a deity, if your one mind can meditate on profundity and clarity, your meditation on the deity unifies wisdom and method. When you do deity yoga meditation, if the one mind does this deity yoga with inseparable method and wisdom, it becomes practice of Vajrayana. Vajra means inseparable method and wisdom and yana means vehicle. It becomes a quick vehicle to enlightenment, to achieve rupakaya and dharmakaya. If either method or wisdom is missing, however, your practice of deity yoga doesn’t become Vajrayana. Since most of the time wisdom is missing, our practice doesn’t receive the name “Vajrayana.”

Offerings to the Self Generation

Blessing the Offerings

Now bless the eight offerings to the self-generation Chenrezig. First, with OM PADMANTAKRIT HUM PHAT, dispel the interferers abiding in the offerings to the self generation.

The offerings to the self generation, to you as the deity, start from your right side. The offerings to the front generation start from your left side, which is the right side of the front-generation deity.

Presenting the Offerings

When you say the offering mantras OM ARYA LOKESHVARA SAPARIVARA ARGHAM (PADYAM, PUSHPE, DHUPE, ALOKE, GANDHE, NAIVIDYA, SHAPTA) PRATICCHA SVAHA, transform offering goddesses from your heart, and they make the offerings. At this point you are making the offerings to yourself as Chenrezig. With each offering, it is good to think, as you did earlier with the merit field, that the offering generates extraordinary, immeasurable bliss within you, the deity Chenrezig. You should feel that bliss.

The bliss that you experience in Action Tantra is not the same as the great bliss of Highest Yoga Tantra, but there is a level of great bliss that accords with this tantra. It is good to generate this experience of bliss, produced by the condition of the offerings.

Blessing the Rosary

To bless the mala, which you hold in your hands at your heart, recite OM GURU SARVA TATHAGATA KAYA VAK CITTA VAJRA PRANAMENA SARVA TATHAGATA VAJRA PADA BANDHANAM KAROMI once, and then OM VASU MATI SHRIYE SVAHA seven times.

According to the commentaries to Chenrezig practice, you should hold the mala in your right hand, with it hanging over your ring finger. But if you cannot do that, you can hold the mala in the usual way. If you’re going to practice pacifying actions, the mala should be either bodhi seed or crystal. Bodhi seed and crystal, or glass, malas are suitable for all four tantric actions.98

Mantra Recitation

After the introduction to the meditation, recite the mantra. It is said that in Action Tantra mantras are counted using the right hand.

While you recite the mantra, send beams from the mantra at your heart, illuminating your whole body and pacifying all your negative karmas and obscurations, all the causes of your suffering. By the way, your suffering is pacified. The power of the mantra and that meditation can help to pacify suffering.

Then emit Chenrezigs from your heart, and a Chenrezig comes above the crown of each sentient being. Nectar flows down and purifies all the negative karmas and obscurations of each sentient being, and they are led to Chenrezig’s enlightenment. All the Chenrezigs are then absorbed back into the syllable HRIH from where you transformed them.

Padmasattva Mantra

Each time you recite the hundred-syllable mantra in a sadhana, you must ring the bell, because it signifies wisdom, or emptiness. By remembering the absolute nature of all negative karmas and obscurations you purify them, and you ring the bell to remind yourself of this. His Holiness Trijang Rinpoche advised that you should ring the bell whenever you recite this mantra in sadhanas or in pujas.

When we recite the Padmasattva mantra after the mantra recitation, the vices of having recited extra mantras or recited mantras incorrectly are purified. So during this time you must ring the bell. The vajra represents method, and the bell, wisdom. What is that wisdom? The wisdom of emptiness. The sound of the bell signifies emptiness; it means that all three—subject, action, object (the negative karmas and vices you have accumulated)—are empty, that they don’t exist from their own side. Meditate by remembering the meaning of the sound of bell. What it’s saying is, “Everything is empty.” Meditate, in particular, that I, action and object (negative karmas and vices) are empty. Remembering emptiness again in this way brings incredibly powerful purification.

Do the same thing each time you recite the Padmasattva mantra. You can understand the particular context from what comes before the recitation of the Padmasattva mantra—the meditation is then the same.

Also, you can do the Padmasattva visualizations in relation to either yourself or other sentient beings, whom you have visualized as the deity.

notes

97 See chapter 19 for more details. [Return to text]

98 Pacifying, increasing, controlling and wrathful. [Return to text]