If modern technology is used in a positive way it has the potential to benefit billions of people and animals in the world. But used in the wrong way it can bring unbelievably disastrous harm to billions of beings. This is especially true of digital technology, the Internet and so forth, which has the power to benefit immediately, sending images and words all over the world in a second, but at the same time it also has the power to do great damage, harming billions of people, polluting their minds, destroying their lives. It all depends on how such things are used.

In a positive way the benefits from life to life are unbelievable. Watching His Holiness online, for instance, allows the mind to develop like a lotus opening, bringing greater happiness, more success from life to life, for hundreds of lives, thousands of lives, millions and billions of lives. It leads to the total liberation from the oceans of samsaric suffering and ultimately to the total elimination of all obscurations and the completion of all realizations, to that peerless happiness, where there is no trace of ignorance, no obscurations. Therefore, we must be very careful how we use modern technology.

Buddhism comes to Tibet

In Tibetan Buddhism there are four traditions: Nyingma, Kagyü, Sakya and Gelug. When the Nalanda Monastery abbot Shantarakshita went to Tibet to purify the land, he built the first monastery in Tibet in Samye. However, each night, after the human beings had erected the monastery walls during the day, the spirits would tear them down so that the next day the people would have to rebuild them. This happened again and again.

So King Trisong Detsen invited the powerful yogi Padmasambhava from India to visit Tibet. There is a whole book—probably several books—on the life story of Padmasambhava. When he got to Tibet, he arose in the aspect of an enlightened wrathful deity and hooked the spirits. Three ran away according to the karma of the Tibetans, but he subdued the other twelve and made them pledge to protect and not harm the Buddhadharma in Tibet and to protect its practitioners as well. Having been subdued, those twelve spirits became Dharma protectors. Since then, Tibetans have been making offerings and doing prayers to those protectors and asking them for help. From that, Buddhism became firmly established in Tibet.

Thus the Buddhadharma came to Tibet from India, from Nalanda Monastery—not Nalanda in France but Nalanda in India. And speaking about Nalanda in France, that is now a real monastery, not a diluted one, because they now do the three main practices of a monastery there: the twice-monthly confession ceremonies, the yearly abiding in summer retreat and following Vinaya.15 It also fulfills the description of a monastery in that it is isolated from villages and crowds. In Nalanda in India there were three hundred pandits. After the Buddha achieved enlightenment and revealed the teachings, great pandits like Asanga and Nagarjuna, who was like a second Buddha, came. These great pandits were holy beings who actualized the path. They were not just scholars, not just experts in words whose minds remained ordinary—these three hundred holy beings all actualized the path.

The Buddha’s teachings are contained in the Kangyur, a collection of more than a hundred volumes, and the commentaries to the Buddha’s teachings by those great Indian pandits are contained in the Tengyur, a collection of more than two hundred volumes. This is what came from India to Tibet. In that way, there is a vast and pure lineage within Tibetan Buddhism that can be referenced back to the Buddha himself. It’s not like some black magic made up by Tibetan lamas.

Before Buddhism came to Tibet there was the Bön religion. There were the black Bönpos, which I think was a form of shamanism, and the white Bönpos, whose teachings seem similar in subject to dzog-chen but using different language. The founder of the Bönpo was Yungdrung Tonpa. I don’t know if the white Bönpos take refuge in him but he is not a buddha. It’s like in Hinduism there are Shiva and Maheshwara and other deities who are not buddhas.16

The teachings of most of the lineage lamas of the four Tibetan traditions can be traced back to Nalanda, so we can say that Buddhadharma in Tibet, both sutra and tantra, came from Nalanda and, therefore, the Buddha.

After Padmasambhava subdued all the spirits in the different important places of Tibet and they became Dharma protectors, Buddhadharma spread, mainly in the monasteries, where there was extensive study, as deep and wide as the Pacific Ocean. From the commentaries by the Nalanda pandits, the great Tibetan teachers wrote their own commentaries. The many enlightened beings from all of the four traditions, such as Lama Tsongkhapa, all studied extensively, listening, reflecting, meditating and then actualizing the path. After that, they wrote commentaries based on their own experiences and taught others the path that they themselves had practiced and actualized.

At that time there were a great many lay practitioners and ordained Sangha living in caves. There were so many caves that the mountains were like ants’ nests. Now so much has been destroyed or has become old and ruined. I didn’t see the whole of Tibet when I went there, only that which was on the way to Lhasa, but in the early times it must have been amazing.

These great lamas actualized the whole path to enlightenment, the extensive study, the middle study and the heart study. The Kadampa geshes started with Lama Atisha, the great pandit who in the eleventh century was invited from India to Tibet to make Buddhism pure again when its practice in Tibet had degenerated and there was much misunderstanding of tantra. People felt that if they practiced sutra they could not practice tantra and vice versa. There was much confusion.

Seeing this, the Dharma king of Tibet, Lha Lama Yeshe Ö, collected gold to offer to Lama Atisha in order to invite him to Tibet. He first sent the translator Gyatsoen Senge to India but he could not meet Lama Atisha and was therefore unable to invite him.

The second time, while Lha Lama Yeshe Ö was looking for more gold to offer Atisha, he was captured by an irreligious king and put into prison. In order to free his uncle, his nephew, Jangchub Ö, offered the gold meant for Lama Atisha but the irreligious king said that there wasn’t enough, that gold the size of the king’s head was still missing and that to free the king he had to be offered gold the size of the king’s body plus his head.

When Jangchub Ö reported this to his uncle, the Dharma king said, “I will die in prison for the sentient beings in Tibet and to spread pure Buddhism, so don’t give him even a handful of gold. Take all the gold to India, offer it to Lama Atisha and invite him here.” The king sent Atisha a message that he would meet him in his next life. Then the translator Nagtso Lotsawa went to India carrying the gold. He offered it to Lama Atisha and explained all the problems and misunderstandings prevalent in Tibet.

So Lama Atisha asked Tara, the female embodiment of all the numberless buddhas’ holy actions, whether he should go to Tibet to spread the pure Buddhadharma. He often prayed with great devotion to Tara for success, as did many great yogis, lamas, pandits, Sangha and lay practitioners, because Tara had manifested specifically in order to fulfill the hopes and wishes of sentient beings. Tara said, “Your time in Tibet will be highly beneficial but your life will be shortened by seven years.” Lama Atisha replied, “I don’t mind if my life becomes shorter, as long as it’s beneficial for Tibet.”

He then pretended he was going to Nepal on pilgrimage, not telling the monastery or the Indian people that he was going to Tibet, because they would not have let him undertake such a long journey. In that way he went to Tibet via Nepal.

When Lama Atisha arrived in Tibet, Jangchub Ö explained the situation fully to him, telling him, “We Tibetans are very ignorant, so please explain refuge to us.” Jangchub Ö didn’t request initiations or teachings on shunyata or other high teachings. This is what he requested of Lama Atisha. Lama Atisha was extremely pleased, so he wrote a short text, the Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, in which he integrated all the teachings of Buddha into what has become known as the graduated path to enlightenment.17

He was able to condense the essence of the 84,000 teachings of the Buddha—all the Hinayana teachings, the Mahayana sutra teachings and the Mahayana tantra teachings, the three levels the Buddha taught—into a few pages. He made how to practice very clear, without any contradiction between sutra and tantra practice, so people could practice both. Those who practiced tantra could also practice sutra and those who practiced sutra could also practice tantra. That helped so much.

In those days, before newly written works could be published they had to be checked by a group of pandits. If a text was found to be correct it would be approved for publication but if it had mistakes it would be tied to the tail of a dog, which would then be chased around the city by people proclaiming the name of the disgraced author. So before making his text available Atisha sent it to his monastery for review. The pandits there were extremely surprised by the quality of Lama Atisha’s writing and praised him highly for writing it.18

After that, many other great meditator lamas wrote commentaries on that first lamrim teaching according to the experiences they had had by reading, reflecting and meditating on it. Lama Tsongkhapa, who was one of these, wrote the most elaborate commentary (the Lamrim Chenmo, The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment), the Middle Length Lamrim, a short one called Songs of Spiritual Experience and, finally, the very short Three Principal Aspects of the Path to Enlightenment. The term “lamrim” comes from Lama Atisha’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment.

Thus the misconceptions about Buddhism that prevailed in Tibet were completely eliminated, the Dharma was made pure and much sutra and tantra was practiced and actualized.

Attaining enlightenment comes from the base, the two truths: the truth for the all-obscuring mind and the truth for absolute mind. These two truths are the base, the path is practicing method and wisdom—putting the essence of method and wisdom into the path—and the goal to be achieved is the buddha’s holy body and holy mind. This is the entire Buddhadharma, and both sutra and tantra are what the monks studied in the monasteries in Tibet for their whole lives. Through that, numberless meditators became bodhisattvas and were able to achieve buddhahood, becoming enlightened beings.

In many other holy places in Tibet practitioners also achieved realizations; not only Milarepa but many others attained enlightenment there as well. Because of that, there are many, many places in Tibet that are unbelievably blessed.

Just as the pandits did in Tibet, you Western students also need to study what is written in the texts and, through intensive contemplation, meditate on and actualize the path. You must try to hold in your heart the teachings that the Buddha and those other great holy beings in India and Tibet explained. If you can do that then the West too can become an extremely blessed place, like India, Nepal and Tibet.

Otherwise it is just studying words, as people do at universities. Of course, you have to start with words, but without actualizing the path in your mind, without transforming your life, then it is merely study. It is still unbelievably fortunate that you can do it, but it’s not Buddhadharma as found in India, Nepal and Tibet. When tsampa is thrown into a river it doesn’t sink, it stays on the surface. Likewise, if the Buddhadharma you study does not enter your heart but just stays on the surface, all you’re doing is studying words. It’s kind of empty. However, I think there are many people who are learning and trying to meditate and practice, and gradually this is having a beneficial effect on their mind. That is very good.

The Buddha manifests in an ordinary form to guide us

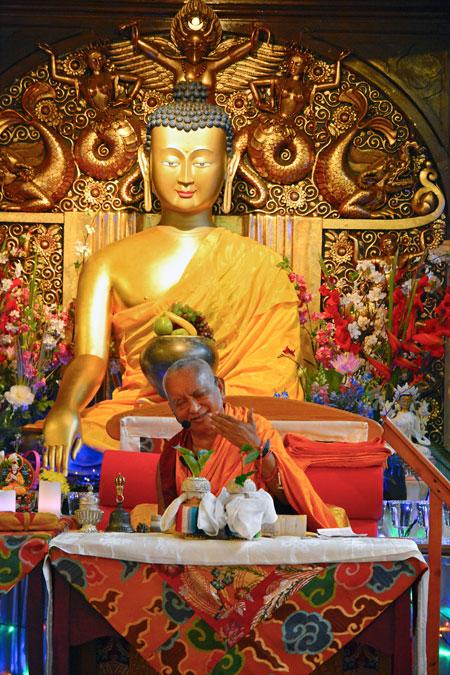

His Holiness the Dalai Lama is the sole object of refuge for the numberless sentient beings of the six realms: for the beings of the hell realm, the hungry ghost realm, the animal realm, the human realm, the god realm, the demigod realm and the intermediate state. He is the sole object of refuge for all sentient beings including us. He is the embodiment of the compassion of all the numberless past buddhas, present buddhas and future buddhas, the definitive meaning of Avalokiteshvara, the Compassion Buddha.

The buddhas manifest in human form in order to show us how to be free from the lower realms, from samsara and even from the peace of lower nirvana. Through their guidance we can become free from all subtle obscurations and actualize all realizations and so attain buddhahood, the peerless state of the omniscient mind. In order to guide us, to explain the teachings in a way that we can understand, the buddhas manifest in an ordinary aspect, in a human form.

“Ordinary” means this. Although for them there is no suffering of rebirth, they show the suffering of rebirth; although they have no suffering of old age, they show the suffering of old age; although they have no suffering of illness, they show the suffering of illness; although they have no suffering of death, they show the suffering of death.

Arhats are free from only the disturbing-thought obscurations, not the subtle obscurations to knowledge, yet they are free from these four sufferings. So how can enlightened beings, who are free from even the subtle obscurations, have old age, sickness, death and rebirth? Since there is no cause for these sufferings, it’s impossible. The buddhas don’t have these sufferings but they show the aspect of having them for our sake.

Take Guru Shakyamuni Buddha, for example. According to the Mahayana teachings, in reality the Buddha achieved enlightenment numberless eons ago. He did not become enlightened two thousand six hundred years ago in Bodhgaya. All the twelve deeds were to show us what to do. Taking birth in Lumbini, achieving enlightenment in Bodhgaya, teaching the Dharma and passing away in Kushinagar—performing all these holy deeds was purely to show us the path.

In many universes at different times the Buddha simultaneously shows different aspects of the twelve deeds. While the Buddha was taking birth here in this world all those centuries ago, in another universe he was showing the aspect of becoming enlightened. Even now, in one universe he is showing the aspect of passing away while in another he is showing the aspect of sitting under the bodhi tree, and in yet another he is showing the aspect of turning the Dharma wheel. He manifests in numberless aspects without effort and gives various teachings in numberless different universes to numberless sentient beings. This is beyond our imagination.

According to the Hinayana teachings, the teachings for that level of mind, his enlightenment in Bodhgaya was the first time, but according to the Mahayana, the Buddha was enlightened eons ago and he performed the twelve deeds just to show us suffering sentient beings that although there is suffering that none of us want, there is both a cause for that suffering and a path that leads to its cessation.

Rather than complaining that we are suffering and never doing anything about it, we see that there is an evolution; that suffering is a dependent arising. Since any suffering we are experiencing depends on causes and conditions, if we apply the correct method, the cause of suffering—karma and delusion—can definitely be eliminated and we can become free from it.

The Buddha showed us that our mind has this possibility, this potential. Because there is a path we can actualize we can definitely achieve ultimate happiness, the blissful state of peace for ourselves, liberation forever from the oceans of samsaric suffering. We can learn, we can reflect, we can meditate on the path and we can actualize it.

Emptiness only, tong-pa-nyi

In particular, we can actualize the direct perception of emptiness, emptiness only. That only—nyi—makes it a specific emptiness, not just any emptiness. The nyi cuts ordinary emptiness.

Not understanding this specific emptiness is the root of our suffering, the root of the oceans of samsaric suffering, the sufferings of rebirth, old age, sickness, death and so forth. And that is only the suffering of pain, which is not the only suffering in samsara. There is also the suffering of change and pervasive compounding suffering, which is the cause of the other two.

We are afraid of cancer and many people die from it, but they don’t know that the root cause of cancer is not understanding this particular emptiness. It is also the root cause of AIDS and all the other diseases that medicine has no cure for, not to mention all the other sufferings of samsara, not just sickness. It is where all our relationship problems and depression come from. It is the cause of anorexia, bulimia, obesity and all other eating disorders. This ignorance is the very root of the problems experienced by every individual, by every family, by every society, by every country, by the entire globe. Whatever suffering there is, this ignorance is the root.

All problems come from this root, which is a wrong concept, therefore this wrong concept is what we need to eliminate. By studying, reflecting and meditating, by realizing the ultimate truth, we can come to realize that this concept is totally wrong.

I don’t understand emptiness well so I can only explain it in a simple way. There is a base—the five aggregates—that exists and, depending on that, the thought of the I arises. For instance, if the base, the aggregates (in this case the body), is sitting, then the thought of the I arises, the merely labeled, “I am sitting.” We label this on the sitting aggregates.

When the aggregates stand up, again there is the thought of the I. The aggregates are the base upon which the I is labeled. There is the subject that labels the I and the aggregates that are the object. When the aggregates are standing, the thought of the I merely imputes, “I am standing.” When the form aggregate is standing, the thought of the I doesn’t label, “I am sitting.” No. The thought of the I is dependent on what we do. When walking, the thought of the I merely imputes, “I am walking.” Whatever action we are doing—eating, standing, sitting, sleeping, lying down—the aggregates are doing the action and then, on top of that, the thought of the I is merely imputed and we believe it.

When the aggregates are jogging to become skinny—maybe that’s not correct, maybe it’s to become fit—then the thought of the I merely imputes “I am jogging.” When the aggregates are talking, depending on that action, the thought of the I merely imputes, “I am talking.” We put the I on the action of talking, or “I am in silence” or whatever it is.

When we are meditating, in dependence upon the mind meditating the thought of the I, the subject, applies the label, “I am meditating.” We call the merely-imputed I and the merely-imputed action of the I “meditating.”

So, depending on what the aggregates—our body and mind—are doing, depending on the action, the labeling thought merely imputes the I and merely imputes the action of the I.

From the moment we wake up in the morning until we go to sleep in the evening, all day long, depending on what our body and mind does, the labeling thought merely imputes the I and the merely labeled action of the I, whatever the I does. The I and the action of the I—whatever we have believed from morning until night—has all come from our mind, has all been labeled by our mind.

This meditation is incredibly powerful, like an atomic bomb, destroying our enemy. An atomic bomb is considered the most powerful weapon to destroy an external enemy. Ordinary people in the ordinary world believe that the true enemy is the external enemy. According to Dharma this is not so at all, and this mindfulness meditation is really the best way to destroy the one true enemy, the inner enemy.

What we do to protect this nonexistent real I

If we do some profound scientific analysis, some inner scientific analysis, we can see how much we believe in this totally real I that actually does not exist. It appears to be real from its own side, we believe it to be one hundred percent real, but it is not there. By doing this inner scientific analysis, this meditation, we can come to see this very subtle point, the nonexistence of this “real” I.

Otherwise, without checking, because of our belief in its reality we have all these worries, all these fears. Because of this wrong projection, when somebody passes us with her nose in the air, looking down at us disdainfully, it hurts so much. Or when we do a good deed for somebody, such as giving a thirsty person a glass of water, and don’t even get a simple thank you, that really hurts. Being shouted at, being complained about, hearing disrespectful words—all these things hurt us.

Especially nowadays, with the world economy in recession, people are trying to find ways to make money, so they complain about any small thing that somebody else does. I don’t know about England, but I’ve heard that in America you are supposed keep the front of your house clear of snow and if you don’t clear it away well enough and somebody falls over you will be sued, which in America means a huge expense.

There is a good example from the FPMT center in Sicily, Centro Muni Gyana. Once, while I was giving a talk there a student explained how she had been sued. Her job was assisting in the births of babies, delivering them from their mothers’ wombs, and one day a baby had died. I’m not sure whether the baby was dead in the womb or it died during delivery, but the mother blamed this girl, telling her she had killed the baby, that the baby died because she had made a mistake. The girl talked with all her friends and they confirmed what she did was right, that it wasn’t her fault, but the mother blamed her and wanted money from her. She was trying to make money out of the situation. This is just one example.

Nowadays, with the downturn in the world economy, many people are trying to make money in this way, trying to prove that somebody else has made a mistake, whether they have or not. The girl asked me what to do and I did my own Mickey Mouse divination and told her to recite the Vajra Cutter Sutra eight times. She did this immediately and later she told me that she had won the court case.

Just reading the Vajra Cutter Sutra is unbelievably powerful but, of course, the main thing is to realize emptiness, to eradicate the very root of samsara. That is what reading the Vajra Cutter Sutra eventually does. Then we become free from oceans of samsaric suffering, achieving ultimate happiness. Without talking about enlightenment, just that is unbelievable.

Our whole life is spent being afraid of something happening to this I, to this real I that appears to us from there. We totally, one hundred percent believe it is real and do everything we possibly can to protect this real I, which is not there. We see all the possibilities of being hurt. “This will make me sick. This will kill me. This will hurt me.” We take every possible precaution to prevent this real I that doesn’t exist from being hurt.

Determined to keep fit, we do hours of exercise every day, jogging or working out on machines. There is a big industry making new types of machines for our real I to keep fit on. After a machine has been on the market for a few months a new one comes out and our real I has to have it. Each machine makes us exercise differently—from lying upside down to putting our head between our legs—and we are forced to buy new ones because the experts in advertisements convince us that these new ones are better.

All this is done for our real I, for the I that appears real and we believe one hundred percent is truly there. Even exercising the body, doing many hundreds of pushups, is for this real I. Everybody jogging, running and exercising is doing it so that this I does not get sick. They are protecting this I. They have injections to prevent diseases before they happen. They take every single precaution they can to protect this real I.

If we were to meditate for just one day, analyzing, checking, going to a subtler level, we would see that this real I is not there. What appears as the real I, what we believe one hundred percent to be real, is not there. However, we don’t check and this labeling process goes on continuously. It has been going on since we were born and will continue up to death.

Because the aggregates—the body and mind—are there, because they exist, they are the valid base on which the labeling mind merely imputes the I. Then, depending on what that base does, the labeling mind merely labels the action.

The labeling thought merely labels I on the subject and the merely labeled action on whatever the aggregates do. It has been and will be like that, from the time our consciousness entered the fertilized egg in our mother’s womb until our death, when the extremely subtle mind, what we call the subtle mind of death,19 leaves from the heart, the place where it entered the fertilized egg at the very beginning. This happens after the person is clinically dead: after the breathing has stopped, the heart has stopped beating and there is no more brain function.

When we analyze, we can understand very clearly the great difference between the reality of the I and actions and how we believe they exist when we don’t think about it. The way we normally think is a total hallucination, a total illusion; it is like a dream.

From beginningless rebirths up to now there has always been the continuity of existence of the aggregates, although not necessarily always of the physical body—a formless realm rebirth doesn’t have a physical body. And just as there has always been the valid base, the aggregates, their continuity, there has always been the labeling thought that merely imputes the I and merely imputes the action of the I, depending on what the aggregates do. When we analyze dependent arising—not the gross one but the Prasangika view of subtle dependent arising—we see that it has always been like this from beginningless rebirths up to now.

How everything appears to us as truly existing

As long as there is the continuity of the valid base, the aggregates, there is always the mere I existing and there is always the mere action of the I existing. While we are circling in samsara it will be like that. This will not change, even after we become enlightened, when our mind is totally free from subtle obscurations and completes all the realizations. It is like that forever.

The I exists and the action of the I exists because the valid base exists. They exist in mere name, not from their own side. Even the valid base exists in mere name.

Saying the I exists “in mere name” does not mean that it does not actually exist. It exists, but the way of existing is unbelievably subtle. This is incredibly interesting. The way of existing is so subtle that, for our hallucinating mind, it is like it does not exist. In fact, for our hallucinating mind, what exists—the merely labeled I—seems to be nonexistent and what doesn’t exist—the real I—we totally, totally believe in. When we check, when we search, when we meditate, using our inner science, we find that what really exists seems to be nonexistent to the hallucinated mind.

Our normal life is totally like a dream, like a hallucination, like an illusion, like a mirage. By thinking about what really exists, we can understand the hallucination. By considering what is the truth in life we can understand what is false in life. Otherwise we can know neither the full truth nor what is false.

To summarize, the valid base, the aggregates, is there. Because of that, the thought of I arises, the merely labeled I and the merely labeled action arise, depending on what the valid base does.

In the first moment the labeling thought merely imputes the I and the action. For instance, if the I is sitting—if sitting is the merely labeled action of the I—there is firstly the merely labeled I and then secondly the merely labeled action, “sitting.”

Therefore, it is so subtle. How the I exists is extremely subtle; it is never the way we normally believe it to be from birth; from beginningless rebirths in fact. It is never the way that our mind projects it to be—truly existent. The I that exists is extremely subtle. It’s like it doesn’t exist compared to how it appears to our normal hallucinated mind.

That happens in the first moment. In the second moment, when it appears back it should appear back as merely labeled. It has just been merely labeled by our mind a moment ago so it should appear back to us like that. But for us that is not what happens. It only appears back to the buddhas as merely labeled, only to those beings who have no disturbing-thought obscurations, for whom there is no trace of negative imprints at all. Only the enlightened beings, the buddhas, apprehend it as merely labeled. Until that time, for us sentient beings, we have this hallucination of the truly existing appearance because the negative imprints of the disturbing-thought obscurations have not yet ceased.

There are sentient beings who are arya beings, who have the direct realization of emptiness only, shunyata. When their mind is in equipoise meditation they don’t have the dualistic mind, the appearance of true existence. However, in the post-meditation break time, they have the hallucination. Even with bodhicitta and compassion, they still all have the appearance of true existence. For us, however, the moment after the mind merely imputes the I, it appears back as a real I, not as a merely imputed I. This is a huge hallucination. How does that hallucination happen?

Take color, for instance. We see light appearing from an object, such as black letters on white paper or a bunch of roses appearing as white and red. Or when we are driving and see a traffic light appearing as red, we stop. The red color appears to exist from there but actually it is our mind that has imputed that red. We don’t see that this is so. Just as with the I, everything that appears to our senses appears in this way. There is this hallucination. This is exactly what the Heart Sutra refutes.

To understand how all phenomena appear like this, the I is a good example. The reason the merely labeled I appears as a real I is because of past ignorance holding the I as truly existent, while it is not, while it is totally empty of existing from its own side. That particular ignorance has left a negative imprint on the mind and that negative imprint projects. Firstly, depending on the base, the mind merely imputes the I, then in the next moment the negative imprint left by the past ignorance projects the real I. It projects it just as a film put into a movie projector is projected onto a screen. The real I has never existed in that way and it will never exist in that way.

And then, in the third moment, we believe that this I really exists as it appears. In Tibetan it is called ti-mug ten-dzin ma-rig-pa, the ignorance holding the I as truly existent. That concept, that this is real, is the root of samsara, the root of all the sufferings of samsara. It is where all the suffering of rebirth comes from, where all the suffering of sickness comes from, where all the suffering of old age comes from, where all the suffering of death comes from, where all the suffering of pain comes from.

If, for example, we don’t want cancer, we have to realize emptiness and eliminate this gross wrong concept of the self-existent I. By eliminating it, none of the three poisonous minds of attachment, anger or ignorance or any of the other delusions can happen and we therefore cannot experience the oceans of the suffering of samsara.

Similarly, what is the root of all our depression? Some people get depressed when the sun sets, some at night, some in the morning, but always at a fixed time. For some it is dependent on the situation. Some people spend years and years suffering from depression. Where does it come from? It comes from this root, this wrong concept from where all the suffering of pain originates.

With respect to the suffering of change, all temporary samsaric pleasures—pleasures that neither last nor increase—arise because they are in the nature of suffering. This also comes from the same wrong concept.

These two types of suffering, of pain and of change, come from the third type of suffering, pervasive compounding suffering, the root of all these sufferings. For Buddhists, this is what we should be free from. This is what we should understand. This is the suffering we should generate the wish to be free from. The way we free ourselves is by actualizing the path, thereby achieving ultimate liberation.

The root of even that basic suffering is this wrong concept. All problems come from this: global problems, countries’ problems, family problems, society’s problems, the problems of individuals who live in a city or who live in the wild—even insects’ problems and those of dinosaurs as well.

When we consider this belief in the real I, this thing that is the root of all our problems, it is very interesting. It is colorless and shapeless, without physical form. It is just a concept, just a way of thinking. This concept is the total opposite of the reality of how the I exists. It is the total opposite of how the aggregates exist. We have this wrong concept and then we believe in it. This is so subtle but this is where the whole of our suffering comes from.

How do we eliminate this? The essence of Buddhism is renunciation, bodhicitta and right view. So it is very important to study, understand and reflect and meditate on the right view in order to develop the ultimate wisdom realizing emptiness. By developing a direct perception of emptiness we are able to eliminate this disturbing thought-obscuration, this wrong concept, the seed of these wrong concepts and achieve nirvana, the sorrowless state, the blissful state of peace.

The Prasangika view of emptiness

What eliminates the root of ignorance is the right view according to the Prasangika, the most subtle of the four Buddhist philosophical schools: Sautrantika, Vaibhashika, Cittamatra and Madhyamaka, which has two sub-schools, Svatantrika and Prasangika.

Even though each school has an idea of ultimate reality, it is the Prasangika view that really cuts the root of the oceans of samsaric suffering: the suffering of pain, the suffering of change and pervasive compounding suffering. The only thing that can completely eliminate that ignorance is the Prasangika view of emptiness, emptiness-only, shunyata. To bring us to that understanding, the Buddha gave us the teachings on dependent arising, which have the power to lead us to the end of samsara.

Padmasambhava, Nagarjuna and Asanga as well as Lama Tsongkhapa—all of them—actualized the Prasangika view and were therefore able to give teachings from their experience and to guide us, helping us to be free from the oceans of samsaric suffering and bring us to full enlightenment. Whatever it is called by different people, whether it is called emptiness or not, it is this specific emptiness, the Prasangika view.

Our understanding of emptiness can only be considered correct if it helps us understand subtle dependent arising and does not contradict it. If it contradicts dependent arising—if, instead of supporting dependent arising, it leads us to the conclusion that there is no dependent arising, there is no existence—that means there is a mistake in our understanding.

Lama Tsongkhapa uses the example of a vase (vases and pillars are common examples in debating texts). He says when we check and see that there is no vase—that the top is not the vase, the neck is not the vase, the belly is not the vase, the bottom is not the vase—if we conclude that there is no vase at all, this view of emptiness does not help us see how the vase does exist. Unless our conclusion is an understanding of dependent arising—the truth for the all-obscuring mind, conventional truth—we are led into a sense that there is no vase, and that is nihilism.

That meditation leads to nihilism when we begin with the big mistake and leave out the object to be refuted. When we look for the vase that exists, from the very beginning we fail to touch the object of refutation, that which does not exist. What we are looking for is the general vase and in the end we conclude that there is no vase.

Many people believe that is the correct way of meditating on emptiness. There are debaters in the monastery—geshes even—who debate well but still think that this is the correct meditation to do, without touching the thing we have to realize as empty, without touching the gag-cha at all. This is what we are looking for.

Lama Tsongkhapa very clearly mentioned this in both the Lamrim Chenmo and the Middle Length Lamrim. There are many pages emphasizing gag-cha, the object to be refuted, explaining it and clearly showing what we need to understand in order to realize emptiness.

If the previous meditation were correct, then why would we need to understand the four-point analysis?20 The other meditation does not touch that at all, it does not even question it, and so what the meditator is looking for is incorrect. It might help some people initially, but finally it will prove to be incorrect. That is why the four-point analysis must come first.

Only if the meditation on emptiness supports the understanding of dependent arising and does not contradict it in any way can we say it is a correct meditation on emptiness. So, you can see, these two things are not separate. Dependent arising and emptiness are not two separate phenomena. In Tibetan, dependent arising is ten-ching drel-war jung-wa or ten-jung. Ten, “dependent,” eliminates nihilism and jung, “arising,” eliminates eternalism. That is the middle way, neither nihilism nor eternalism.

What is a dependent arising is empty of existing from its own side, being merely labeled by the mind. Nothing exists from its own side. And emptiness is a dependent arising. In that way dependent arising and emptiness are unified.

Notes

15 These are customs the Buddha established for monasteries. So-jong (Tib.) is a confession ceremony where Sangha members admit any wrongdoings; abiding in summer retreat (Tib: yar-ne) occurred every summer in India during the rainy season; and following Vinaya means following the rules of discipline that the Buddha laid down. [Return to text]

16 Bön is the religion in Tibet that is often said to have preceded Buddhism. His Holiness the Dalai Lama has recognized Bön as the fifth tradition along with the four major traditions of Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyü and Gelug. Practitioners of Bön are called Bönpos. The founder’s full name was Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche. Yungdrung is the name of one of the Bön traditions, they do consider Tonpa a buddha and the Yungdrung school is essentially Buddhism. Some scholars assert that Bön arose only in the eleventh century and was therefore not a pre-Buddhist religion in Tibet and that the religion that did precede Buddhism was probably not called Bön. [Return to text]

17 (Tib: lamrim). See Teachings from Tibet, appendix 2, for a translation of Atisha’s text. [Return to text]

18 See Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, pp. 49–50. The book contains a complete biography of Lama Atisha. [Return to text]

19 Tib: sem shin-tu tra-mo. [Return to text]

20 Also known as the four vital points of analysis, this is one of the main techniques for meditating on emptiness. [Return to text]