THE FIFTH PARAMITA: THE PARAMITA OF CONCENTRATION: SAMADHI MEDITATION

The following conditions are necessary for us to achieve the fifth paramita, the perfection of Concentration (Tib., Sam.tan)

- We should be in a well-contained place.

- We should have little desire.

- We should be satisfied with sense objects.

- We should avoid distracting work.

- We should be morally pure.

- We should avoid the superstitions that make us attached to sense objects.

As there has not been time to complete this section of the Meditation Course book, the following has been copied from The Opening of the Wisdom Eye by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, published by the Theosophical Publishing House, Madras, for the information of students.

The Training In Supreme Collectedness (Adhisamadhi-siksa)

Only the person trained in virtue can train in collectedness. Usually the mind (citta) 9 does not remain fixed for long upon one object since it is flickering here and there, being engaged with the objects of the various sense-fields, but through this training it can be made one-pointed or perfectly concentrated. When the mind is concentrated upon a skilful object and not disturbed, then that one-pointedness of mind is called “samadhi.”

Samadhi or collectedness10 may be analysed into various levels of mental absorption (dhyana). These are preceded by access collectedness (upacara-samadhi) in which the five hindrances (nivarana) 11 commonly arising in the lower planes of desire are suppressed; but when the factors of absorption (dhyananga) arise, this is the level of attainment collectedness (arpana-samadhi). Collectedness is of two kinds, worldly and transcendental. The worldly variety is also of two sorts: pertaining to the form realm or else to the formless realm and within these two realms there are eight levels (bhumi), four in each realm. If by correct practice one has attained the absorptions both of form and of formlessness, then one has fulfilled the perfection of collectedness (samadhi-paramita).

As we pointed out above, collectedness is classified as either worldly or transcendental. Here, by “world,” one should understand, are meant the three world-elements (loka-dhatu) within which all living beings are found12. Thus worldly collectedness is that which has worldly objects and produces a worldly result, that of calm and happiness in this life and for the next, gives rise to a celestial birth (the experience of “heaven,” “paradise,” etc.) Unworldly or transcendental means that this sort of samadhi is aimed at freedom, its objects being essence-lessness and not-selfsoulness (nihsvabhavata, anatmata). In order to achieve worldly and transcendental absorptions, one should first develop calm and insight (shamatha-vipasyana).

Although at first one may seem to develop these aspects of samadhi separately, finally one must develop the collectedness in which they are yoked together13. The aspect of collectedness which pacifies the fickleness of the mind is called “calm,” while that wisdom which penetrates to the three marks (of existence)— impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and not-self-soul—is called “insight” (vipasyana, literally: deep insight).

The order of development regarding these two aspects of collectedness in the mind is first calm (shamatha) and then insight (vipasyana), or as they may also be termed: mental development (bhavana), and that including thorough examination. Once the mind is well established in calm, the development including examination which yields insight becomes possible. Shamatha is the calm and serene pond in which the fish (the faculty of deep insight) moves in examination. This is so because the mind at that time is fixed strongly upon its object and not easily disturbed14. This state is very important and the skilful karma made while dwelling in it, is very powerful and of great fruit.

There are five obstacles15 to this development of calm which are sources of disturbance and stand opposed to tranquillity. They are:

- Mental slackness (kausidya) creating discouragement so that the mind is not interested in the practice of collectedness. This is opposed by the mental factor called “determination” (chanda).

- Lack of mindfulness (musitasmrtita) in achieving collectedness, for if this is to be experienced there must be constant mindfulness to ensure that the mind is established with concentration upon its object. Through lack of mindfulness the object of collectedness disappears from mind. This factor, therefore, is opposed to perfect (or right) mindfulness (samyak-smrti).

- Next comes sinking and scattering of the mind (nirmagnataauddhatya). “Sinking” means that the mind becomes submerged without awareness in the object, a state which bars further progress. It is necessary during meditation to be mindful of the object, while at the same time the mind should not sink into it. “Scattering” is a kind of fickleness of the mind because of which the mind cannot remain fixed upon its object. This pair of obstacles oppose clear comprehension.

- Association with the above pair of obstacles (samskarasevana) is itself counted as an obstacle to collectedness. In this case one knows that the mind is overpowered by sinking and scattering but still one does not make an effort to develop those factors which oppose them and are able to cure the mind.

- It sometimes happens that having made this effort and produced the counteractive factors, one goes on practising them at a time when they are not needed (samskarasevana disassociation). This is an ignorant way of practising and shows that the mind is not fully aware or focussed upon its object.

It is impossible to achieve the perfection of collectedness unless one puts away these five opposing factors.

For training the mind to avoid these five there are eight dharmas which stand in opposition. They counteract the obstacles in this way:

- Trust (sraddha) opposes mental slackness.

- Determination (chanda) opposes mental slackness.

- Perseverance (virya) opposes mental slackness.

- Tranquillity (prasrabdhi) opposes mental slackness.

- Mindfulness (smrti) opposes lack of mindfulness.

- Comprehension (samprajanya) opposes sinking and scattering.

- Investigation (samskaracintana) opposes association with the above.

- Equanimity (adhivasana) opposes non-association.

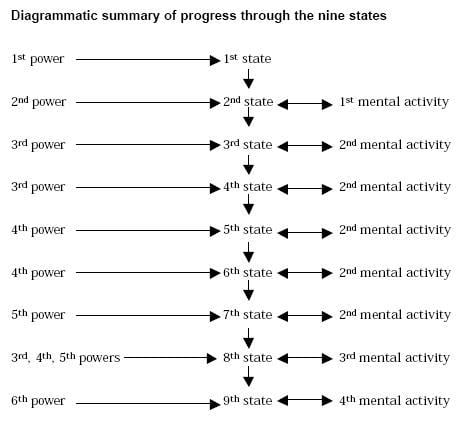

Calm should be developed by the growth of these eight qualities. Now we shall go on to discuss the nine states of mind, the six powers and the four mental activities and how, due to them, collectedness is achieved.

Nine states of mind

- Cittasthapana. This is the state in which the mind first becomes unaffected by outer objects and fixes in the meditation object.

- Cittapravahasamsthapa is the establishment of the stream of mind, meaning that the mind is fixed upon the object for some time by compelling the mind to consider again and again the object of concentration.

- Cittapratiharana is the state when, the mind being disturbed, one “brings back” the mind to the concentration-object.

- Cittopasthapana is the state in which the mind is expanded while exactly limited to the object.

- Cittadamana—“mind-taming’’ which is done by seeing the ill results of distracting thoughts and defilements, also perceiving the advantages of collectedness, so that one makes efforts to put away the former while establishing the mind in the latter.

- Cittasamana—“mind-calming” in which feelings antagonistic to the practice of collectedness are quelled. If boredom arises regarding collectedness since the mind is still hungry for sense objects, then it is thoroughly pacified at this stage.

- Cittavyupasamana or the subtle pacification of mind. Even the subtle stains of mind are set aside here.

- Cittaikotikarana. The mind here becomes like one undisturbed stream and continues to flow along one-pointedly.

- Samadhana. When this state is reached, there is no need for effort since the mind is naturally one-pointed.

Six powers

- Srutibala: Listening to a teacher or else reading books on the method of fixing the mind, such is meant by this first power.

- Asayabala: By the power of repeated thought one establishes the mind in the way of collectedness.

- Smrtibala: If the mind becomes distracted by some other object, it is by this power of mindfulness that it is returned to the meditation-object and established therein.

- Samprajanyabala: By means of this power of clear comprehension one comes to know the evil results of the mental stains and the beneficial fruits derived from collectedness thus making one delight in the latter.

- Viryabala: This sort of skilful energy ensures that the mind is not influenced by the stains.

- Paricayabala: The natural and thorough acquaintance of the mind with collectedness, forced application of mindfulness and clear comprehension being no longer needed.

Four mental activities

- Manonivesapravartak-manaskara. By means of this activity the mind enters into the object.

- Vicchinnapravartak-manaskara. Although the mind may in the beginning remain in concentration for some time, every now and then distraction will arise from the obstacles of sinking, scattering and so forth. This activity returns the mind to its object.

- Avicchinnapravartak-manaskara. Through this activity the mind is established in the object for a long period thus giving no chance to distractions.

- Ayatanapravartak-manaskara. When all the hindrances to collectedness have been set aside, it is through this activity that the mind is held effortlessly upon its object.

The successive attainment of collectedness 16

Now having given an outline of the various factors involved in the approach to collectedness, the subject to be explained here will be the progress through the nine states of mind and the hindrances which are encountered in them and how the various powers and mental activities bring them to an end.

As I said above, the first power consists of listening to the teaching and making the mind learn about the objects of concentration. Those who have heard this kind of teaching and who desire to experience collectedness, do not allow their minds to stray upon exterior objects. When the mind begins to be established in this object, it is called the first state of mind. Although the mind begins to be established in the object, it fails to be concentrated upon the same object for a long time. Thoughts pour from the mind like water in a waterfall and it seems as though a veritable flood of thoughts arise. The truth is that the mind has always been in this state but never before was one aware of it, since one had never turned one’s gaze within before. Now that the mind is turned inward because of the practice of mindfulness and clear comprehension, these thoughts become known. Just as upon a great and crowded highway, a careless person may not be aware how crowded it really is unless he examines carefully to see the different sorts and numbers of people, so in the same way the mind begins to know the variety and range of thoughts comprising it. This should not be regarded as a fault of practice but quite a natural experience for one beginning to take up concentration.

While experiencing the first state of mind, it is by means of the second power that the mind is repeatedly established upon the object. In this way the mind becomes restrained for some time by this power and so reaches the second state of mind. Here thoughts sometimes arise and disturb the mind after which they die away and it is then that the meditator realises for the first time the stopping of thoughts. Two faults are commonly found here: sinking and scattering. If the former then the mind sinks gently into the object and a sort of sleep is the result, while the latter makes the mind fickle and run after other objects. The result of these is that one’s collectedness loses power and force. When this occurs, one should fix the mind unwaveringly upon the object and where this occurs, it is known as the first mental activity.

However, if after the mind has been earnestly tied to the object it is continually being disturbed by other objects, then it must be established again upon the object of concentration by the third power (of mindfulness). One will then reach the third state of mind.

As I said above, whenever the mind is not energetic and hence gets discouraged due to the faults of sinking and so on, then it is directed by the third power to return to the concentration-object. Likewise, this power of mindfulness is needed to limit the mind when expanded, from straying to other objects. This is the fourth state of mind.

While practising concentration, thoughts and stains appear repeatedly and this is because the meditator does not know the unskilful and distracting results to be expected from them, nor does he realise the skilled fruits of collectedness. When by way of the fourth power (clear comprehension) one notices and comes to know these faults, then they can be properly dealt with by means of this power. This means that stains already arisen are cut off, the mind being well established in the object, and when this occurs it is known as the fifth state of mind.

From time to time the mind is liable to become dissatisfied with concentration so that from the arising of boredom there is the experience of scattering. By means of the power of clear comprehension the bad fruits of this scatteredness are known thereby not permitting the mind to entertain boredom. This is called the sixth state of mind.

As far as this stage of practice is concerned, although faults and stains have been suppressed by reflection upon their unsatisfactory results for the future, this does not mean that they will not arise again. For this reason the meditator should beware. Whenever these stains become manifest in the mind, then the real value of awareness may be seen for whatever the stain, whether greed, lust, singing, and so forth, and whether arising in a gross or in a subtle form, it can be ended with this awareness where it is supported by earnestness and effort. This is the seventh state of mind.

Although from the third up to the seventh state the mind has been concentrated to a greater or lesser extent, even when well established in the object, stains such as sinking and scattering and so on will cause distraction from time to time though perhaps only after long intervals. This results in one’s collectedness being broken and at such a time this is restored by the second mental activity. This activity has its application in all states of mind from the third to the seventh.

If the meditator develops both the third and fourth powers to counteract scattering and the fifth power against sinking, then these two stains will not arise as hindrances to collectedness. As a result of this, one’s practice proceeds like an unbroken stream, this being the eighth state of mind.

While experiencing this state if one makes an effort carefully and persistently, then these two stains have no power to break into collectedness so that it proceeds unbroken and quite undisturbed, the third mental activity thus being found in this state.

Persistently and continuously developing collectedness, it is through the sixth power that the object becomes very clear. In this state, the mind is effortlessly concentrated on the object without the support either of mindfulness or of clear comprehension. One has then reached the ninth state of mind. Just as a man who has learnt the scriptures well may, while chanting them, let his mind wander elsewhere, yet there is no hindrance to his chanting, so the mind which has been previously well established in the object is now fixed there effortlessly and without any hindrance. The current of collectedness is now able to flow for a long time without effort made by the practicer, this being the fourth mental activity. The ninth state of mind is also called “access collectedness’’ (upacara samadhi).

Calm is found even in the mind of a meditator who begins to practise for the attainment of collectedness. As the strength of calm increases so stiffness both of mind and body decrease. This stiffness, dullness or unworkability of mind is associated with heaviness and mental inactivity, all of which are aspects of that root-cause of the mental stains, delusion (moha). When we say that calm stands opposed to stiffness, we mean that this calm or shamatha is accompanied by lightness both of mind and body17. In a calm mind, joy (priti) arises and because of this the mind becomes established in the meditation object. The calm of mind also gives rise to a tranquil and relaxed body, such bodily peace being very helpful to the meditator.

As one progresses with collectedness this joy tends to decrease while equanimity (upeksa) replaces it, the mind being established in the object with greater stability, an experience known as samadhi-upacara-acala-prasrabdhi (literally: the unshaken tranquillity of access to collectedness) and with it one enters a state very close to the first absorption (dhyana).

By continuing one’s practice in this way, one does in fact reach the first absorption. We have already said that there are three great levels (bhumi), sometimes called world-elements (dhatu) but these may be further subdivided to make up a total of nine levels:

- Sensuous-existence level (kama-bhumi).

- First absorption level (prathama-dhyana-bhumi).

- Second absorption level (dvitiya-dhyana-bhumi).

- Third absorption level (tritiya-dhyana-bhumi).

- Fourth absorption level (caturtha-dhyana-bhumi).

- Sphere of infinite space level (akasanantyayatana-bhumi).

- Sphere of infinite consciousness level (vijnananantyayatanabhumi).

- Sphere of no-thingness level (akincanyayatana-bhumi).

- Sphere of neither-perception-nor-nonperception level (naivasamjna-nasamjnayatana-bhumi) also called the summit of becoming (bhavagra).

These successive levels are attained by having no attachment for them and by seeing the advantages of the levels higher than those already attained together with the disadvantages of those already reached.

These absorption-attainments (dhyana-samapatti), that is the last eight of these nine levels, are causal factors since by means of their attainment (when a man) one may be reborn among the celestials of form or formlessness (according to the type of absorption reached).

His Holiness then goes on to describe the method for the attainment of the absorptions, the fruits of accomplished absorptions, the four formless absorptions and special virtues and knowledges.

SHAMATHA (QUIETUDE) MEDITATION (Shi-nä)

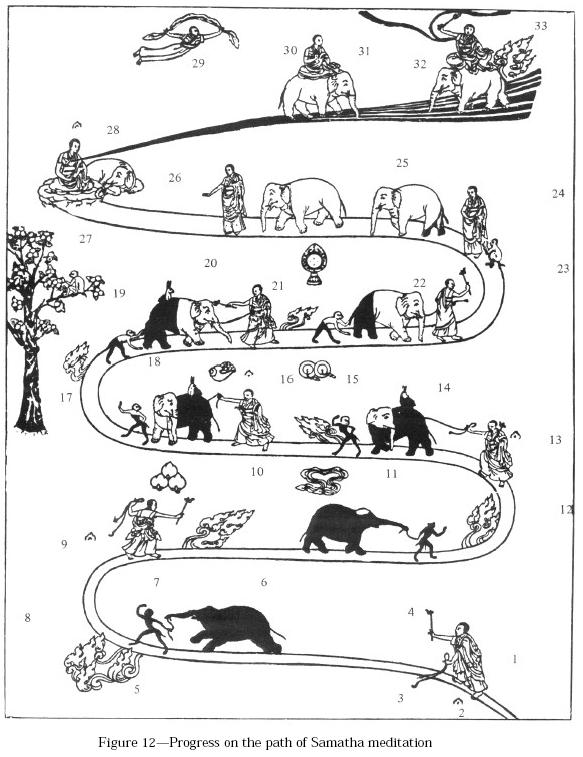

- The first is the force of hearing. The first stage of meditation is attained through the force of hearing.

- Fixing the mind on the object of concentration.

- The force of recollection (mindfulness).

- The force of consciousness (clear comprehension).

- From here until the seventh stage of mental absorption will be found a flame decreasing in size at each progressive stage until it becomes conspicuously absent. This difference in size, absence and presence of the flame denotes the measure of effort and strength of recollection and consciousness.

- The elephant represents mind, its black colour the mental factor of sinking.

- The monkey represents interruption (distraction), and its black colour the mental factor of scattering.

- The force of reflection. This achieves the second stage of mental absorption.

- Uninterrupted and continuous absorption on the object of concentration (lengthening of the period of concentration).

- The five sensual desires are the object of the mental factor of scattering.

- From here the black colour, beginning from the head, changes into white. It denotes the progress in the clear grasping of the object of meditation and prolonged fixing of the mind on the object of concentration.

- The force of recollection. The attainment of the third and fourth stages of mental absorption is achieved through the force of recollection.

- To return and fix the strayed mind on the object of concentration.

- The hare represents the subtle aspects of the mental factor of sinking. At this stage, one recognises the distinct nature of the subtle and gross aspects of the mental factor of sinking.

- Looking back means that having perceived the diversion of the mind, it is again brought back to the object of concentration.

- Maintaining a clear conception of even the minutest details of the object of concentration.

- The force of consciousness (clear comprehension). Through this is attained the fifth and sixth stages of mental absorption.

- The arising of the mental factor of scattering preceding the actual state of absorption is greatly reduced.

- At the time of Shamatha meditation, even though thoughts of virtue arise these have to be eliminated and the mind tenaciously projected on the object of concentration. The reason is that such thought, in spite of its virtuousness, will act as interruption. Such elimination is not necessary when one is not doing Shamatha meditation.

- The force of consciousness (clear comprehension) arrests the mind from drifting astray, and because of its sheer loftiness, the mind is drawn towards absorption.

- The mind is controlled.

- The mind is pacified.

- The force of mental absorption are accomplished through the force of mental energy.

- The mind becomes perfectly pacified. At this stage the arising of the subtlest sinking and scattering will not be possible. Even if there occurs some, it will be immediately removed with the slightest effort.

- Here the black colour of the elephant has completely faded out, and the monkey has also been left out. The meaning represented is: bereft of the interrupting factors of scattering and sinking, the mind can be settled continuously in absorption (on the subject of concentration) with perfect ease and steadfastness, beginning with the application of a slight amount of the forces of mindfulness and clear comprehension.

- One-pointedness of mind.

- The force of perfection. The ninth stage of mental absorption is attained through the force of perfection.

- Perfect equanimity.

- Ecstasy of body.

- Attainment of mental quiescence of Shamatha.

- Mental ecstasy.

- The root of samsara or becoming is destroyed with the joint power of Shamatha and the direct insight (vipasyana) with Shunyata (void) as the object of concentration.

- The flame represents the dynamic forces of recollection (mindfulness) and consciousness (clear comprehension). Equipped with the power, one examines the nature and the sublime meaning of Shunyata (void)—the knowledge of the ultimate reality of all objects, material and phenomena.

PRAYER TO BE SAID AFTER MEDITATION EIGHT

From the Profound Tantric Text, Guru Puja

With this prayer visualise: Guru Shakyamuni, surrounded by Vajradhara, the Infinite Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and Arhants, Dakas and Dakinis, many other Tantric Deities, the Protecting Deities, and all the Holy Gurus in the direct and indirect Lineage of the Teachings, sending much light to me and to all sentient beings, who are visualised as surrounding me.

This light is absorbed into me and into all sentient beings, purifying all negativities and obscurations, and bringing all Knowledge—especially the Knowledge of how to abandon mental dullness and mental agitation that I may accomplish the Perfection of Concentration by single-minded concentration on the ultimate nature of all things.

J’ING.GÖ NAM.PAR YENG.WÄ KYÖNG.PANG.NÄ

CH’Ö.KÜN DEN.PÄ TONG.PÄ PÄ NÄ.LUG.LA

TZE.CHIG NYAM.PAR JOG.PÄ TING.DZIN.GYI

SAM.TÄN P’AR.CH’IN DZOG.PAR J’IN.GY’I.LOB

(By abandoning the faults of mental dullness and mental agitation, please bless me to accomplish the perfection of concentration, by single-minded meditation on the ultimate nature of the voidness of all things.)

After this prayer, complete the visualisation as described on pp. 16-18 and dedicate the merits with the prayer on the last page.

Notes

9 Usually the term “citta’’ is translated as “mind” but it really means the total mental-emotional experience of which one is aware as well as that of which one is not aware. It embraces: feelings (pleasant, painful, and neither); perception, memory (of objects: visual, audible, smellable, tasteable, tangible and mental objects); volitional activities (such as those associated and disassociated from consciousness); and consciousness. When we translate ‘‘citta” as “mind” this implied Buddhist significance should be remembered. [Return to text]

10 Sometimes translated as ‘‘meditation” which however is too vague a word in English for use in Dharma. [Return to text]

11 Nivarana—the five hindrances: sensual desire, ill-will, sloth and torpor, worry and remorse, scepticism, all of which are obstructions to the attainment of the absorptions (dhyana). [Return to text]

12 The world-elements (dhatu) of sensuality, form and formlessness. The first of these comprises, from the “lowest” (spiritually) “upwards”: the hells, animals, hungry ghosts, men and celestials of the sensual realm. In the form world-element are found the celestials of Brahmaloka (the Brahma-gods), as well as those now in their last birth as non-returners (anagami) who attain Nirvana in the Pure Abodes which are the highest planes of this world-element. The formless world-element comprises four states of existence known as infinity of space, etc. Birth in these realms is strictly in accordance with one’s karma, i.e., if one allows one’s mind to become dominated by lust, birth follows as an animal, if one keeps the Five Precepts one is a man and will be born as one, and if one makes efforts with training, then one will be born upon the level to which one has been successful in training the mind. Only by right application of Wisdom can one go beyond the three world-elements (lokadhatu) scattered throughout space. In modern terms these would be called galaxies except that the modern and materialist term takes no account of the great range of possibilities for life known to Buddhists. [Return to text]

13 It is important to note this point and to beware of meditation teachers who stress that “insight” only is enough. Some of them offer “methods” which “guarantee” Enlightenment, insight, etc., within a limited time of practice, and some offer a graded series of stages and “interpret” a disciple’s progress by his little experiences as representing this or that insight-knowledge (vipasyana-jnana). [Return to text]

14 Insight (vipasyana) is developed with the five heaps (skandha) as one’s basis and with some aspect of them as one’s object. The states of absorption and their approaches tend to produce in a meditator all sorts of visions, ecstatic experiences and unsurpassed powers, etc. These things easily lure him off the practice path which for a Buddhist leads inwards to the nature of the five heaps and not outwards to these distractions. A meditator has to give up all these experiences and use his concentrated mind to penetrate to the marks of the five heaps: impermanence, duhka, no atman, voidness. [Return to text]

15 In Theravada Tradition, the five hindrances oppose entry upon the absorbed states but are in turn opposed one for one by the Five Posers, thus: trust (sraddha) opposes sensual desire (kamachanda); energy (virya) opposes ill-will (vyapada); mindfulness (sati) opposes sloth and torpor (thinamiddha; Skt., styanamiddha); collectedness (samadhi) opposes worry and remorse (uddhaccakukucca); wisdom (panna) opposes scepticism (vicikiddha). [Return to text]

16 For this process clearly depicted see the large illustrated sheet prepared by the Council for Cultural and Religious Affairs of H. H. the Dalai Lama (reproduced p.184). [Return to text]

17 Called “lahuta” (Skt., laghuta), lightness, and grouped in Theravada Abhidhamma with tranquillity, softness (pliancy), adaptability, proficiency and uprightness of both bodily and mental factors. [Return to text]