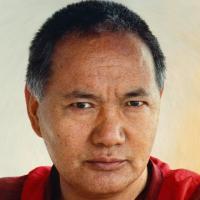

Rinpoche’s previous incarnation and early life

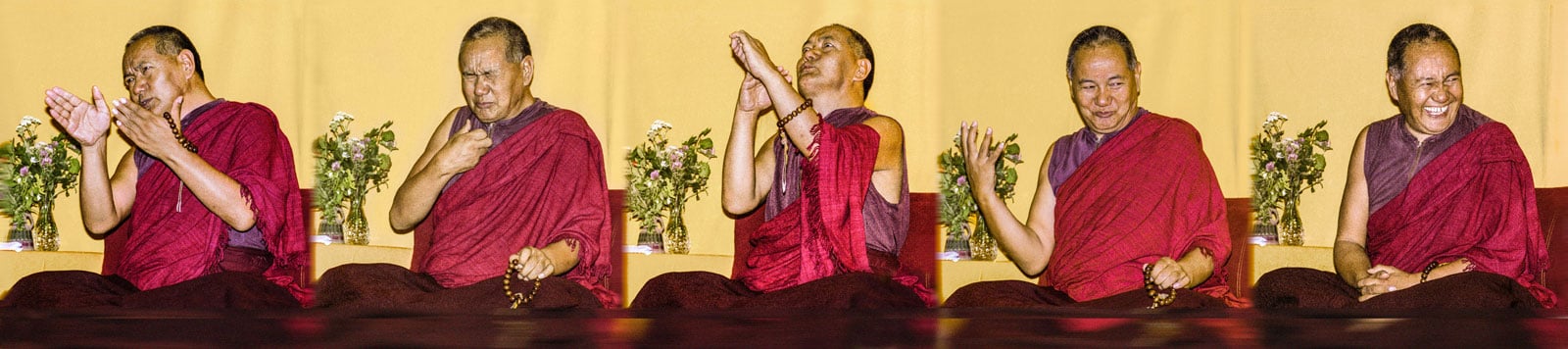

You’ve asked me about my previous incarnation. I think the past life sentient being did a good job because I have been able to meet the Dharma in this life and have had the great opportunity to meet His Holiness, the actual Compassion Buddha in human form. I have met so many extremely qualified teachers and heard teachings on the path to liberation and enlightenment from their experience—not just from books but from their own experience. They are completely learned and totally pure and good-hearted, with all the qualities. I have met many great gurus and I have met not just the Buddhadharma Hinayana teachings but the Mahayana Paramitayana teachings that reveal the five Mahayana paths and ten bhumis where you can achieve full enlightenment and liberate numberless sentient beings from the oceans of samsaric suffering and bring them to full enlightenment. And especially I have met the Mahayana Secret Mantra Vajrayana teachings, especially the Maha-anuttara Yoga Tantra teachings that have the greater skill, allowing you to achieve enlightenment in one brief lifetime of degenerated time.

I have met all those teachings and particularly Lama Tsongkhapa’s teachings that are unmistaken and include sutra and tantra, all the stages of the path to enlightenment. They are unmistaken in how to achieve renunciation, unmistaken in how to achieve bodhicitta, and unmistaken in revealing the Prasangika school’s view on emptiness. In reality there is only one truth of emptiness, that of the Prasangika Madhyamaka school. By meditating on emptiness unified with shamatha, calm abiding, this brings the experience of the rapturous ecstasy of the body and mind. This is special insight. To achieve this, you need to achieve shamatha as the foundation.

To achieve shamatha correctly, you need to cut the two distractions, sinking and the attachment-scattering thought. This is not just the scattering thought but the attachment-scattering thought because there are also virtuous scattering thoughts. The scattered mind that can be virtuous is called to wa in Tibetan. The attachment-scattering thought (Tib: go pa) has attachment clinging to this life. There are both the gross attachment-scattering thought and the subtle attachment-scattering thought. And then there are both the gross sinking thought and the subtle sinking thought.

Many learned meditators of the past were mistaken in thinking that they had achieved perfect shamatha because they were unable to recognize the subtle sinking thought and so were unable to remove it.

Gross sinking is mental fogginess, like bad weather, like the sky covered with thick fog. Like that, the mind is foggy; you can’t really meditate, the object of meditation doesn’t come to the mind. Or the mind can hold the object but there’s no clarity. That’s the gross sinking thought. With the subtle sinking thought the object is perfectly clear but you lose the intensity; the way of intensively holding the clear object is not there.

Lama Tsongkhapa’s teachings, both on sutra and tantra, are like refined gold, with extremely detailed explanations of the generation stage and completion stage of tantra, then the illusory body. Such detailed explanations didn’t happen before Lama Tsongkhapa.

I have heard all those inconceivably profound extensive teachings on sutra and tantra that will undoubtedly leave a positive imprint. So, I think my incarnation in the past life did a good job. But I think this life’s incarnation is not so good! My past life did a very good job, so I have to thank the past life for leaving all those positive imprints that make it possible for me to achieve all the realizations. However, I didn’t get to actualize them, so this life is not very good.

Everything is dependent arising, depending on cause and conditions. Hell is dependent arising, enlightenment is dependent arising. Hopefully I can make my life more meaningful, more beneficial for sentient beings, if it’s possible in this life. I try to collect merit on the basis of correctly devoting to the virtuous friend and I hope to have some realizations and then in the next lives, in future lives, I hope I can benefit sentient beings even more. I think that’s about it.

It’s not that I can remember past lives, if that’s what you were asking about. In my case my belief in past lives is because I must have done some meditations on the certainty of past lives, not because I have had realizations. This is the result of past effort.

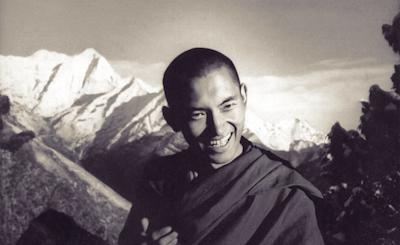

There was a lama who lived in a cave at a place called Lawudo. He wasn’t a monk but a lay yogi, a lay practitioner. Other people said that the lama came from Tibet, close to the snow mountains, and he lived in the cave for many, many years. By that time he was old and had knee problems, knee pain. He meditated and lived a simple life, living in the cave and from time to time giving initiations and teachings to the people. The other lamas who knew him seemed to respect the way he lived.

People say that when I was a small child, around three or four or five, I mentioned that I was his reincarnation and I would often try to go to the cave, not completely up the road, just some of the way.

There are three ways of checking on possible reincarnated lamas. The first way is that the child says something that make people suspect, and then some high lamas use their subtle wisdom to check. The mind has three levels: gross, subtle and extremely subtle. They check with the subtle mind, the one that functions in sleep. They normally meditate with that mind, what is called utilizing ignorance on the path, but what that really means is using sleep on the path to enlightenment by stopping the gross mind and allowing the subtle mind to arise and then meditating on emptiness and achieving enlightenment. That’s putting it in a simple way, without describing much of the secret points. Anyway, some lamas check about reincarnations through their subtle wisdom.

The other way is by giving the child a choice of various religious implements, malas and cymbals or whatever, that were used by that lama or his monastery in a previous life, mixed with others. While people are watching, the child is supposed to then choose the correct implements, the ones his previous incarnation or his monastery used. I don’t know if this happened all over Tibet but in Solu Khumbu, the Himalayan ridge near Mt. Everest, this was very common practice, to bring things and spread them out on the table and ask the child to pick up the correct ones, to check whether they can remember.

When I was a very small child at home, I ate food made by my mother and then spent all day long playing outside with other children. I had a friend who was mute, who couldn’t speak. He was the child who played most with me in the fields and then there were some other children who came to play from time to time. Much of the time I pretended to be a lama giving an initiation! The other children played being my students, bowing down. I pretended I was giving initiations or doing pujas in the fields where there was water and many small stones. I mixed the earth and water to make mud for torma and then made offerings to the Sangha or things like that.

There was a monastery quite close to my family home in the village of Thangme. The monastery was a little bit up, the home was down in Thangme. Because of that my mother sent me to the monastery when I was very small to learn the Tibetan alphabet. She sent me to my uncle, who was a monk in Thangme Monastery. He was very good, he knew how to carve mantras on the rocks and there were many rocks by the roads in the upper part of Solu Khumbu which he had carved with many mantras: Padmasambhava’s mantra, OM MANI PADME HUM, Manjushri’s mantra and some other buddhas’ mantras. A family would sponsor it and it took a few months to finish but when it was finished it was very beautiful with the mantras painted black or white on the rock. Then, whenever people passed it on the road on the way up they would circumambulate it and the same on the way down. They did that to collect merit, to benefit many sentient beings who were travelling, such as the people and the animals, like the dzo, yaks or cows or whatever. All the time they received great benefit and purified negative karma collected from beginningless rebirths and planted the seed of enlightenment.

When the carving was finished they had a celebration, drinking wine, which was as common as drinking coffee in the West, at home, in the office, everywhere. Up there, wine was made from different grains, but unfortunately it became sort of degenerated. There were some monks who didn’t drink wine at all but many did. It became a habit but there were some who didn’t drink. They put grain into big containers made of wood and it became alcohol, then people drank it by sucking the alcohol with glass or bamboo pipes. Then they did pujas and performed tsog offerings. When that was finished usually all the lay people danced, joining hands and moving around in a long line, singing ancient songs that had words mostly praising the lama, so it was more or less Dharma.

Nowadays nobody does that. When I was in Solu Khumbu, those songs usually praised the lama or the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha or the five Dhyani Buddhas, things like that. The tunes were very good. It kind of brought peace and made the mind very calm and peaceful. Then, everybody offered scarves and danced and everybody went away happily. My uncle teacher did that for much of his life.

I escaped to home from my teacher two or three times. I was very naughty; I wasn’t a good student. I think that’s why my understanding of the Dharma is very limited and what there is, is nothing. I think that was from being very naughty. Anyway, I escaped to home two or three times. As a child the thought just comes without analyzing whether it’s beneficial or not, whether it’s harmful or not. The thought came and I did it.

I have many uncles and because I had escaped a few times my mother sent me away to another uncle in an even more hidden, more undeveloped place. Actually, all these places are Padmasambhava’s holy hidden places where there are many of Padmasambhava’s caves. The other hidden place was Rolwaling. To get there from the other side of Solu Khumbu you had to cross the snow mountains, which for common people took three days, but the Sherpas themselves didn’t take that long. On the mountain there was no particular road so somebody who knew where to travel guided you. Sometimes you walked over the rocks and sometimes on snow. There was a rope tied to each person’s waist because there were many cracks in the rocks covered by snow that might cause you to slip and fall down into the water. If somebody slipped, the person behind could hold the rope and that person would be saved. Once you fell down it was very deep. You had to put the stick first before you placed your foot on the ground. Therefore, the guide must be somebody who knew the route.

As a small child I was always carried; I never walked. One time my teacher—my uncle who was my second teacher not my first—carried me back from his home to this side of Solu Khumbu. It was common to carry cooked meat for the journey there and back. The people of Rolwaling, that more hidden place, were mostly not very intelligent and much more primitive than those in Namche Bazaar near Mount Everest. As I was sitting on his back, on the luggage, with the blankets and food and things my teacher had to carry, he passed pieces of meat to me. In that way I was taken care of.

The first time I was taken to the other more hidden place, Rolwaling, I fell down, not on the ice but just on snow. My uncle slipped and I fell down. When you come from Rolwaling to Namche Bazaar, there’s a snow mountain—I don’t know the name—and quite close to the ground there are lakes of different colors between the snow mountains. That’s all you saw up there. There were no flowers except one that looks like cotton. Those of you who have been on the mountain might remember a high plant all covered with flowers like cotton. That’s all you see. Down below, there’s a lake.

When we were there an avalanche happened. There were quite a number of people, maybe thirty people, and when the snow from the avalanche came they lost all their luggage. One man, when he lost his luggage, went with it, falling down the cliff. I don’t think there was danger of falling into the lake because of the rocks, but he only fell a short distance anyway and then picked himself up, got his luggage and sang a song. I guess he must have enjoyed falling down! We weren’t at the center of the avalanche, we were at the side, and the snow wasn’t so thick you would disappear if you fell. Of course, you can completely disappear in one second, and that happened to many people, but when I fell down people could see me. I also screamed!

Anyway, I escaped three times from the monastery to my home. As I mentioned, as a child the thought comes and you just do it. After one of my escapes my mother made pants for me. I never saw my father. I think around the time I was being carried in a small container of woven bamboo he must have died. My family was very, very poor. We owed money to many, many people but we could not repay it. There was only my mother with all the children. Nobody could help her except my sister who became a nun. My mother didn’t want her to become a nun but to stay and look after the family, because you need one elder child to look after the family, but from her side she wanted to become a nun. She was ordained by a great lama and she now lives up there at Lawudo.

All my mother could do was bring the animals out and take them up into the mountain; she had no time to make us food, clean the house or do anything else. Morning and night she did everything as well as going into the forest to collect wood. You had to either go up or down to do this and either way it was very hard work. After our father passed away there was nothing we could do. We were all very small and couldn’t help with anything; she had to do everything. Sorry, my story is going on and on.

One time, when my mother went to get firewood, it had become very late, maybe nine o’clock, and she still had not returned. It was very dark because the moon had not risen; the house was completely dark and we were all children. Of course there was no electricity. Our light was a bunch of burning bamboo twigs. We used the flame of the bamboo to go outside or to see what was cooking. There was also resin from a particular tree that could be put on the stones near the stove and burnt to give some light for cooking.

One of my brothers is Sangye who now lives near Boudhanath. I asked him to be the director of the Lawudo project to rebuild the monastery because the walls developed cracks. An American Peace Corps worker advised us where to dig and where not to dig, so on his advice we built the new gompa. I wanted to make sure that the walls would be sound so the gompa wouldn’t collapse and kill people. At that time there were no monks there but we started building anyway. In the winter we came here [to Kopan], then in summer we went back up there, but that way we lost many children because they went back home in the winter and never returned. It was very expensive because all the food had to be transported. My brother Sangye built the new monastery separately but kept and fixed up the old one because there were many precious statues and it was difficult to find a place to keep them. He thought the monastery was very precious. It was very high up, but people offered many days of free labor, bringing rocks and wood from another mountain, meaning every piece had to be carried on their backs down from their mountain and up ours. There were no animals, let alone cars. There were unbelievable hardships to build that monastery.

At that time we had a second student benefactor. The first one was the Russian lady, Princess Zina Rachevsky. She became a nun in Dharamsala, ordained by the great lama from Ganden Monastery, Lati Rinpoche, who was an attendant to His Holiness Dalai Lama. Lama Yeshe sent her to meditate in the mountains, which she did for a few years and then she passed away there in meditation. She was reincarnated in France. A very high lama from the Sakya tradition, His Holiness Sakya Trizin, predicted that there was an incarnation of this very first student. I think the mother or the father had some connection with Zina, but somehow it didn’t happen that the reincarnation was brought up in Buddhism, to make life beneficial.

That night our mother didn’t return until very late but all we could do was sit on the doorstep and watch the moon come over the trees and talk. After a long time our mother came home with a huge load of firewood but she was not well. The next day she lay against the wall, which showed something was wrong because we all had our fixed place to rest and this was where my brother, sister and I usually rested. She was in pain and unable to eat and because she was too weak to make the fire there was no fire. She just called “Ama, Ama,” calling to her dead mother, our grandmother. We could just look at her helplessly. There was nothing we could do.

Anyway, it was very hard work taking care of us. I hope I have been of a little benefit to the world and to sentient beings to make her life worthwhile, after all the sacrifices she made: carrying me in the womb for nine months and taking care of me as a baby and a child. I knew nothing, just crawling on the ground, and she taught me how to walk, how to stand up, how to speak.

Of course, she didn’t teach me English, the language I’m speaking to you in, she didn’t teach me directly but even my knowledge of English is due to her kindness. When I was a child she protected me from harm and sacrificed herself for me day and night, always working, always fearful for my safety. She cherished me like a wish-granting jewel, and because of that I was able to learn English, travel to other countries and teach the Dharma a little in English. All this came from my mother’s kindness.

Four times a day she always prayed, “May I become like a sun shining in the world. May I become like a snow mountain. May the three realms be controlled by me.” I told her, “Your prayer doesn’t make sense; it has no meaning. The sun rises all the time over the snow mountains.” But later I discovered almost the same prayer in an initiation text, referring to a goddess that protects you when you are traveling or involved in a court case.

There is an old student called Karuna who lived here for many years with his wife, Pam, teaching the monks. They built a house just below here. His daughter and one of his sons are here. When Karuna lived here, whenever he wanted to find a taxi at Boudha he recited that mantra and he got a taxi every time! That’s what he told me.

There was another student who did a retreat in the mountains, not in Solu Khumbu but down below, maybe in Padmasambhava’s cave. He bought some buddha grass or maybe hashish in Kathmandu, and completely filled a briefcase with it. He dressed well, then he chanted this mantra many times, I think in the cave, and then he left. He went to the United States or somewhere and nothing happened on the way, nothing happened at customs. He told me that’s what he did and that was the mantra he chanted, the one that was in the initiation text that was very similar to the one my mother chanted. I was very surprised.

One thing I missed out. One time, after one of my escapes from the monastery at Thangme to home, my mother made me these pants from very cheap cloth that was used for prayer flags, joined at the upper part. That was the first time I wore pants so I didn’t know how to open them! In the afternoon there was maybe a little bit of snow. I was outside and my alphabet teacher went inside to make food, so I was alone. Then, the thought came to go back home so I suddenly ran away. I had one plant—I don’t know the name—that was hollow that I liked to blow like a puja trumpet, so I ran along the road blowing the plant. Sometimes, at the side of the road there were dark caves, but I ran down, nonstop. I had no idea how to open the pants. Where the parts were sown together the seams were full of the eggs of lice, nits. Because we didn’t wash, it was very easy to have lice. Anyway, I didn’t know how to open the pants, so I ran all the way from the teacher’s house to my home with my pants full of kaka. When I reached home, my mother was outside with quite a few people. She opened my pants and cleaned everything.

Anyway, I hope I have made her sacrifice for me for so many years a little worthwhile by learning the Dharma, and by having learnt a little Dharma, to have brought a little benefit to the world, to sentient beings. I hope any positive thing that has happened has been a little worthwhile to help repay her life’s sacrifice for me for so many years with all the worries and fears she had. I hope there has been some positive result from that.

I’m very sorry. You asked one question and then I went on and on and on!

Rinpoche’s mother’s incarnation

My mother passed away and then reincarnated. She was born in Galupa, the next hermitage from Lawudo. There was a lay tantric practitioner, a ngagpa, whose father was the great lama who founded Thangme Monastery. He is not a monk but lay, with long white hair down below like this and a very bald head, like a long-life man. He was very good-hearted and gave teachings and initiations many times, helping people, doing pujas and things like that. He himself did retreats for much of his life. He was a very, very good lama. His son lived in this place called Galupa, the hermitage where there was a great yogi in the past. My mother was reincarnated to his wife. The child, a boy, was a very wonderful child. When my sister went there, there was a monk who did very accurate divinations and she heard that this boy was the incarnation of my mother. After some time, my sister offered a scarf and the child put the scarf on his neck for seven days, even at night, and never wanted to take it off.

The child always talked about Lawudo when he was very young but his parents didn’t allow him to go to see it even though it was quite close. Then my brother went to see him. The child had been waiting a long time to receive my brother who went there to invite the incarnation to Lawudo Monastery to hold a celebration. The incarnation went to Lawudo and many people came to do puja, to celebrate, as well as nuns from a small monastery below Lawudo in a village called Thamo. When the incarnation of my mother came at Lawudo, he circumambulated the temple seven times, which is what my mother used to do every day in the past life. Then he went into the gompa and respectfully touched his head to His Holiness Dalai Lama’s throne, which was carved when we were building the monastery. He bent his head to the low, small throne that was mine and then he went to the altar and bowed his head. This was exactly how my mother used to do it all the time, every day.

He received and returned scarves from everybody, except his father and another monk from Lawudo, an elderly Kopan monk called Tsultrim Norbu. Why didn’t he give his father a khatag, a scarf? I think because of an imprint from the past life. When my mother was living at Lawudo, many people would do nyung näs, the two-day Chenrezig retreat, and we would have to get the water from the next hermitage where there was a stream. When there were two or three people staying at Lawudo there was enough water, but when there were more people we had to get water from there.

When my mother was living at Lawudo, the father of the incarnation—of course at that time the incarnation hadn’t yet happened; my mother hadn’t died— saw that we put the pipe from that stream to bring the water closer to Lawudo, so the Western students could wash when they were there. When he saw that he blocked the water to stop it from coming through the pipe and my mother got very upset. So, I think because of the imprint left from that, even though the very small child didn’t know about this, he didn’t give a scarf to his father. And he didn’t give a scarf to the monk because my mother used to whisper to me that the monk always got very angry.

Later the little incarnation went to the kitchen where my mother had lived and searched until he found the things that my mother used. One very surprising thing was that my mother, being very frugal, collected the plastic shirt buttons in a bottle and my sister had made a shirt for him using those buttons. In very old times, you wore spoons and things on strings because spoons were very precious. There were no shops and no people who could make spoons; they came from very far away, so people wore the spoons on a string. It was the same with buttons. When my sister put the shirt with the buttons from my mother’s bottle on the little incarnation, he said,

“Oh, these are my buttons.” Buttons were very precious.

At that time there was no sugar, no coffee, no sweet tea. Even rice only came three times a year. Now rice has become an everyday food, but when I was there we ate it once at New Year, and another time when my teacher received a Nepalese man who had walked up for maybe seven days, very far, carrying his heavy load. We had rice then because he brought it. Then, on the fifteenth day of the Tibetan fourth month, the Buddha’s day of enlightenment, a full moon night, my teacher uncle went down to the monastery to do a two-day nyung nä, the Chenrezig retreat. Because you can’t have black food such as garlic, onions, meat and so forth, you have to have white food, so they offered curd and rice, and maybe vegetables. My teacher ate half the rice and brought the other half to me, so I got half a plate of rice with curd. In the past, the place was very clean, very pure. Now it’s totally degenerated, totally overwhelmed by businesses and restaurants. It’s totally changed.

So that was one thing. The incarnation could immediately recognize the buttons he had collected and saved in a bottle in his past life. The other very surprising thing was this. The first time my brother went to see him at his home he went with another Sherpa, Ang Puwa, somebody my mother had a very close connection with. The minute they entered the house and sat down, and the incarnation’s mother offered them a drink—I’m not sure if it was tea or wine—the incarnation mentioned Ang Puwa’s name and invited him to drink. This very small child who didn’t know he was coming at all mentioned his name immediately. Then Ang Puwa grabbed the incarnation and placed him on his lap and he himself cried so much. Because my mother was very close to this man in the past the incarnation could remember his name.

There were many instances of proof like this that the boy was the incarnation of my mother. It seems maybe the conception was there a little bit before my mother passed away, however, the child could remember many things. On top of that he was recognized by my guru, Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche, a great lama from the monastery in Tibet near Solu Khumbu. Behind Mt. Everest is Tibet, so his monastery was there. He checked and proved that this was the incarnation of my mother.

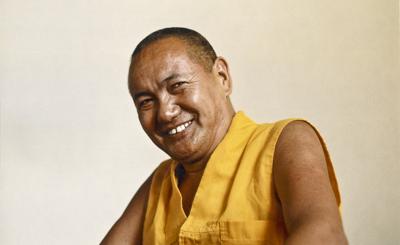

We enthroned my mother’s incarnation here at Kopan Monastery when he was four years old. Whenever he spoke it was unbelievable. His voice was so sweet that hearing it, no matter what he said, brought so much peace to the heart. Anyway, that was my experience. Whenever he said something I waited for him to say something else. As we were doing the enthronement, my idea was that he would study extensive Buddhist philosophy in Kopan: the Buddha’s teachings and commentaries by Nagarjuna, Asanga and the other highly-attained great Indian scholars, both sutra and tantra studied in all the four traditions, Nyingma, Kagyü, Sakya and Gelug. In each tradition highly-attained lamas have written commentaries and some lamas study not just their own tradition but all four. My idea was for him to study all four traditions at Kopan and then after that, he could choose whichever tradition he wanted and practice that. It was up to him.

That was my idea but his parents did not listen to me. They wanted to send him to south India, to the monastery of a very high Nyingma lama. They have nuns as well as monks there and there’s also one section for meditation.

He was only there for fifteen days when there was a storm. He was playing outside and as he ran to go inside to shelter from the storm, he tripped and fell. There were some concrete steps and he banged his head and cracked his skull. He was taken to a small hospital and his parents in Solu Khumbu were called. I was in the West at that time so they didn’t ring me. His parents couldn’t do anything. The person who took the telephone call in Solu Khumbu rang Sangye, my brother, and then he told me. They still didn’t want to listen to me because I was from another monastery. I was disappointed with that. Later he was taken to a bigger hospital and then brought to Nepal. Because the wound was very old nobody wanted to look after him but my brother’s wife knew a doctor, a friend, who checked and saw there was still a piece of bone left in the fracture. He got better for one or two days but then he passed away. So that’s it. The story’s finished.

When Rinpoche was recognized as the Lawudo Lama

I was talking about the examination with religious objects. When I was very small, the lama Karma Tenzin who was supposed to have recognized me from my previous life when I was called Lama Yeshe—another Lama Yeshe—brought religious objects, silver inside and wood outside, to my home. They were spread out on a table at home with some small Tibetan objects and a few different things, but on that day I didn’t point to anything. The next time I was taken to the monastery. In the gompa there was puja. There were many monks there and the lama of that monastery was sitting on the throne, so a big puja was happening. On a side wall there was a life-sized Buddha statue on an altar and in front of that was a very good monk who lived in a cave. I was put on his lap. There were several monks and other people watching, examining. A pile of cymbals from both Lawudo monastery and from other people was placed there. When this lama whose lap I was sitting on asked which cymbal was mine, I pointed in the direction of one and he said, “Yes, that’s correct.” I pointed somewhere but I had no idea! Anyway, the lama said it was correct. I think it’s my karma it happened this way.

Ngawang Chöphel, the heart disciple of the past life’s Lawudo Lama, was there when he was passing away. The Lawudo Lama could recognize all the stages of the death evolution as they happened. He was able to see because of his experience in meditation during his lifetime. He was able to recognize what element was absorbing, what inner and outer signs were happening and so forth. He and his disciple discussed all this as it was happening to him. His disciple told me this when I met him.

After the Lawudo Lama passed away, Ngawang Chöphel went to Tibet and asked a particular lama—I don’t remember the name—if it was correct that I was the reincarnation of the Lawudo Lama. He said it was, but he should go to see another lama, who did a divination and then told him to see another lama. I think he told me he saw six lamas but others have said there were only three. The last lama, Kyabje Trulshik Rinpoche, confirmed that I was the Lawudo Lama.

Ngawang Chöphel did many retreats, many practices and received many teachings and initiations. At one time, following the Buddha’s example, he practiced the paramita of charity by sacrificing his body to the insects for seven days. He built a monastery, this great holy place, like a magical place, where Padmasambhava achieved immortal realizations, in Maratika, which is in Nepal but near to India. Each time they did pujas there in the evening, near sunset, blowing their religious instruments, all the clouds went away and the villagers didn’t receive the rain they needed for their fields. The villagers were Hindus and maybe some other religion and they wanted to burn down his monastery. The queen was Hindu and she wanted to burn down the monastery and kick Ngawang Chöphel out. He ran away before queen came. At the end there was a court case and the government allocated half to Ngawang Chöphel and half to the queen. He was allowed to keep the monastery but he wasn’t allowed to develop it. Kyabje Trulshik Rinpoche told me about him—that he was a Dharma practitioner but he was involved in a court case. Anyway, he passed away sitting in meditation. That happened because of all the practice he did.

Rinpoche said that when he was informed by the attendant that Ngawang Chöphel had died Rinpoche went down and placed a very famous Nyingma prayer on his head. The minute you wear this you’re free from the lower realms. This is what ngagpas, the lay tantric practitioners, those who have their hair rolled up, wear in a silver container. Of course, if you are meditating while you’re dying, you’re completely guided by yourself, you’re completely protected by yourself. He was very lucky that his guru, Trulshik Rinpoche, was there and then he put the prayer on his head. Generally, if you die in meditation—whether lying down or sitting in meditation—depending on your wishes you can get reborn in a pure land or take a perfect human rebirth to gain any realizations you haven’t achieved in the past, and continuously benefit other sentient beings again. Even if there are no other lamas around praying for you, if you die in meditation you can completely take care of yourself.

The disciple of the Lawudo Lama, who built the monastery there, reincarnated7. The last time I went to Maratika to do a few days’ retreat, the incarnation came. It was very nice, very wonderful. Maratika, where Padmasambhava achieved immortal realization, is most amazing. The whole area is like somebody has transformed it into something very magical, even the mountain around it. On the main rocky mountain there’s a vast cave, where there’s a huge, smooth rock like a Buddha Amitayus long-life vase and sometimes nectar comes from it, depending on who prays there. Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, a very high Nyingma lama, went there and nectar came from this huge vase rock. A Japanese Buddhist who wanted to help the monastery and had strong devotion, made a very strong prayer there and again nectar came.

People go there to do long-life retreats. His Holiness Sakya Trizin, the head of the Sakya sect, said that even though astrologically the number of years of your lifespan is finished you can still live five more years. That place has the power to bless you to have a long life. Kyabje Trulshik Rinpoche goes there every year for maybe two or three months to do a long-life retreat for His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

A young Tibetan lady, a dakini who came from Tibet to serve His Holiness, goes there every year to do a retreat for His Holiness. The time before last she did a retreat in a small Padmasambhava cave. I didn’t see her last time because the son of the lama who built the monastery told me not to. You have to climb up a ladder made of tree branches so although everybody else who accompanied me went —a lady, a man and some Kopan monks—because it was late I didn’t go. She did a retreat for one or two months and maybe she didn’t even have food. She saw Buddha Amitayus there for weeks while she was meditating and then she made blessed pills.

I’d better stop here.

[Dedications]

NOTES

7 Read about Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s visit to Maratika in Mandala magazine, June 2008. [Return to text]