The most important thing those of us seeking enlightenment can do is to thoroughly analyze the actions of our body, speech and mind. What determines whether our actions are positive or negative, moral or immoral, is the motivation behind them, the mental attitude that impels us to act. It’s mainly mental attitude that determines whether actions are positive or negative.

Sometimes we’re confused as to what’s positive and what’s negative; we don’t know what morality is or why we should follow it. Actually, it’s very simple; we can check up scientifically. Moral actions are those that derive from a positive mental attitude; immoral actions are the opposite.

For example, when we talk about Hinayana and Mahayana it seems that the difference is philosophical or doctrinal, but when we examine it from the practical level we find that although literally yana means vehicle—something that takes you from where you are to where you want to go—here, this internal vehicle refers to mental attitude.

The practitioner who, having clearly understood the confused and suffering nature of samsara, seeks liberation from cyclic existence for himself rather than enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings has the mental attitude of self-concern and doesn’t have time to look at other mother sentient beings’ problems: “My problems are the greatest problem; I must free myself from them once and for all.” That kind of mental attitude, seeking realization of nirvana for oneself alone, is called Hinayana.

In Mahayana, maha means great and, as above, yana means internal vehicle, so what makes this vehicle great? Once more, yana implies mental attitude and here we call it bodhicitta—the determination to escape from the control of self-attachment and obsession with the welfare of “I, I, I” and reach enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings.6

We often say “I want enlightenment” but if we’re not careful our spiritual view and practice can become almost materialistic. However, those who truly have the innermost enlightenment attitude of bodhicitta seek enlightenment only for the sake of others and thus become true Mahayanists. Those who seek self-realization out of concern for only their own samsaric problems are Hinayanists.

Why do we call these attitudes vehicles? A vehicle is something that transports you—in the case of the Hinayana, to liberation; in the case of the Mahayana, to enlightenment.

We talk a lot about Hinayana this, Mahayana that. We can explain verbally what these vehicles are, but actually, we have to understand them at a much deeper level. It can be that we’re a person who talks about being a Mahayanist but is, in fact, a Hinayanist. What you are isn’t determined by what you talk about but by your level of mind. That’s the way to distinguish Mahayanists from those who aren’t.

However, the way the lamrim is set up is that it explains the whole path; it begins with the Hinayana and continues on through the Mahayana in order to gradually lead students all the way to enlightenment. It also demonstrates the step-by-step way practitioners have to proceed. The realistic way to practice is to follow the path as laid out in the lam- rim. You can’t skip steps and jump ahead, thinking you’re too intelligent for the early stages. Also, in order to experience heartfelt concern for the happiness of others instead of always putting yourself first, you have to start by understanding your own problems. This experience is gained in the beginning stages of the path.

There’s a prayer7 that says,

Just as I have fallen into the sea of samsara,

So have all mother migratory beings.

Please bless me to see this, train in supreme bodhicitta

And bear the responsibility of freeing migratory beings.

It means that first we have to see that we ourselves are drowning in the ocean of samsaric suffering; only then can we truly appreciate the situation others are in. Then, by seeing that, we should not only wish to relieve them of their suffering but also take personal responsibility for their liberation and enlightenment; we must generate the determination to lead all sentient beings to enlightenment by ourselves alone. This is the attitude that we call bodhicitta.

Actually, what is bodhicitta? It’s what this verse explains. It’s not a situation of becoming aware of your own suffering, seeing that others are also immersed in it and then generating some kind of emotional sorrow, “Oh, that’s terrible; how can I possibly help them?” That’s not bodhicitta.

It’s true that we suffer from the problems of ego and attachment and that all sentient beings are in the same situation of confusion leading to samsaric problems. However, seeing that and getting emotionally upset—“Oh, poor sentient beings, but what can I do? I have no method”—is not bodhicitta.

If you get too emotionally worked up over sentient beings’ suffering you can even go crazy. Instead of your insights bringing you wisdom they bring you more hallucination; you pump yourself up, “I’m completely confused and negative, the world is full of suffering, I have no reason for living. I might as well slash my wrists and end it all.”

It’s possible to have this kind of reaction to seeing universal suffering. If you’re not careful you might feel that this distorted compassion is bodhicitta. That’s a total misconception. Bodhicitta requires tremendous wisdom; it’s not based on emotional sorrow. Bodhicitta is the enlightened attitude that begins with seeing that all sentient beings, including you, have the potential to attain enlightenment. Before, you might have felt, “Oh, what can I do to help all sentient beings? I have no method,” but when you see the possibility of leading them to enlightenment, a door somehow opens in your mind and instead of feeling suffocated and emotionally bothered, you feel inspired. Therefore, in the verse I quoted, bodhicitta is described as supreme, perfect or magnificent.

So there are two things we need in order to develop bodhicitta. One is, as it says, “Just as I have fallen into the sea of samsara.” First we have to investigate and understand our own samsaric nature. When we realize that all our wrong conceptions and suffering come from the ego, we can extend that experience to others: “So have all mother migratory beings.” Then, when we see our own potential for enlightenment, we see that all sentient beings have the same potential and take personal responsibility for leading them to enlightenment by attaining it ourself. This intention is bodhicitta; when the two thoughts—attaining enlightenment and others’ welfare—come together simultaneously in the one mind, that’s bodhicitta.

Seeing the possibility of leading all mother sentient beings to enlightenment and taking personal responsibility for doing so is very important. It automatically releases attachment and at the same time your actions naturally benefit others without your having to think about it.

Many people think that bodhicitta is a dualistic mind and therefore somehow contradictory because the Buddha said that enlightened beings have completely released all dualistic minds; they can’t understand why we would purposely cultivate a dualistic mind. Some people engage in this kind of philosophical debate.

However, a mind perceiving a dualistic view is not necessarily totally negative. For example, when we begin to understand the nature of samsara, impermanence, emptiness and so forth, without first cultivating a dualistic view of these topics it’s impossible eventually to realize them beyond the dualistic view.

It’s very hard to transcend duality. Sometimes you can be experiencing a kind of unity but still find it has a dualistic component. The dualistic view is very subtle. Even a tenth level bodhisattva who has gained complete understanding of emptiness still has a slight level of subtle dualistic view.

Also, conception and perception of dualistic view are two different things. You can demonstrate this for yourself by compressing one eyeball slightly and looking at a single light bulb: conceptually, you know for certain that there’s only one light bulb there, but what you see is two. The difference between conception and perception of dualistic view is like that. Therefore, when you first experience the wisdom realizing emptiness, you have the right conception but you still perceive things dualistically.

The reason we have not reached enlightenment since beginningless time is because our relative mind has relentlessly perceived things in a mistaken, dualistic way. The only unenlightened mind that does not see things dualistically is that of the arya bodhisattva in meditative equipoise on emptiness. Everything else is dualistic.

We often feel that analytical meditation is too hard because we have to expend a lot of intellectual energy checking this, checking that, and conclude it would be better just to stop thinking altogether, to completely empty our mind. That’s just ego. How can you stop thinking? Thought runs continuously, like an automatic watch. Whether you’re asleep or under the influence of drugs, thought is always there. Your stomach can be empty but not your mind.

From the perspective of Tibetan lamas, everything that sentient beings’ relative minds perceive is not in accordance with reality. So where does this idea of the mind being empty of intellectual thought come from?

The experience of emptiness is not an intellectual one. If it were, all you’d have to do to experience it would be to fabricate it intellectually, “Oh, this is emptiness, I’m here,” and then you’d feel, “Wow, now I’m experiencing emptiness.” But of course, that’s simply a polluted, deluded, wrong conception mind. It really takes time to experience emptiness. Nevertheless, there are degrees of experience. But for beginners, it’s impossible to experience emptiness intellectually; it’s beyond the intellect.

As spiritual seekers we face two dangerous extremes. One is over-emotionality: “I’m suffering, others are suffering, oh, it’s too much, God help us!” Seeing everything as terrible is too emotional. The other extreme is over-rejectionism: “Nothing exists.” You can’t reject the reality of your own suffering… but through skillful wisdom and practice you can free yourself from it.

What we need to do is follow a middle path between the extremes of seeing everything with too much ignorant emotion as suffering and too much intellectualization as non-existent. But that middle path is very difficult to take.

Therefore Lama Tsongkhapa always advocated the simultaneous development of method and wisdom in order to realize enlightenment and negotiate the two extremes: that of no wisdom and emotional spiritual misery and that of over-emphasis on emptiness and rejection of morality and so forth. Method and wisdom have to be developed simultaneously.

Method means bodhicitta. And not just the words, “Bodhicitta is wonderful!” We have to practice it the way the lamrim explains. If you don’t have a perfect method for developing bodhicitta it will simply remain in your mind as a good idea. Therefore, if you do have a way of developing bodhicitta, you are extremely fortunate. Shantideva and Chandrakirti both explained how to practice bodhicitta, and based on their teachings Lama Tsongkhapa elaborated on how to actualize it in his.

One of the methods especially emphasized by Shantideva was that of equalizing and exchanging self and others [Tib: dag-shen nyam-je]: changing attachment to one’s own happiness to attachment to the happiness of others. For countless lives we have always been obsessed with our own pleasure and have completely neglected that of others. This beginningless focus on our own happiness to the exclusion of that of others is called “self-cherishing.” So we have to totally change this attitude to one of greater concern for others’ welfare than our own.

Actually, this thought is extremely powerful; just generating it automatically destroys the ego. For example, if somebody asks us to serve tea to a visitor, resentment immediately arises within us. We serve the tea, but unhappily. As soon as we’re asked, the buzz of irritation starts in our heart. It’s amazing: we can’t even be happy to give somebody a cup of tea.

The person who changes attachment to self to attachment to others doesn’t have that buzz of irritation in his heart. Without even having to think about it, he’s automatically happy to serve others. Psychologically, that’s very helpful—it stops the pain of self-attachment from arising in our heart.

At the start of our practice, we beginners need tremendous understanding and strong intellectual determination because for countless lives we’ve instinctively thought, “My pleasure is the most important pleasure there is.” Every minute, every second, that thought is there, even if it’s not at the intellectual level. Attachment goes way beyond the intellect and is very well developed in our mind.

In order to destroy the instinctive experiences of attachment and self-cherishing we need to be strongly dedicated to the happiness of others; we do it not through the use of artificial force but by realizing that even the pain of losing our best friend comes from attachment. Nevertheless, even if this best friend asks us for a cup of tea, the buzz of self-attachment can still stir in our heart. It’s incredible.

So we have to think, “Attachment has been a problem in all my beginningless lifetimes and it’s still my real enemy. If I had to name my worst enemy, attachment would be it, because it hurts me all the time and destroys all my pleasure. For countless lives I have been concerned with just my own pleasure, which only results in misery. I must change my attitude from concern for my own pleasure to that of other mother sentient beings. Guru Shakyamuni Buddha attained enlightenment through concern for other mother sentient beings and helping them but because I’ve been on the attachment trip since beginningless time, I’m still totally confused.”

Those who really want to realize enlightenment have to forget their own pleasure and completely devote themselves to that of others. That’s the most important thing. It’s actually a matter of psychology. At first glance you might think that this is just intellectual thought but if you really sincerely concern yourself with others’ pleasure and forget your own, automatically your selfish motivation is released and you have less anger. That’s because anger and hatred come from the selfish motivation that is concerned with only one’s own pleasure. Don’t think about this from simply the philosophical standpoint; check up through your own everyday experience.

For that reason, Nagarjuna said, “All positive, moral actions come from concern for others’ pleasure. Everything immoral and negative comes from selfish attachment.”

So that’s clear, isn’t it? We don’t just make this stuff up philosophically. It’s scientific experience. Check your everyday life: ever since you were born you’ve been dealing with other human beings. You can’t live without involvement with other people; it’s impossible—unless you become Milarepa. But even if you do, you won’t be Milarepa forever.

So bodhicitta is very practical. You don’t have to intellectualize too much. Just check up every day how the self-cherishing thought agitates your mind. Even if somebody asks you for a cup of tea you get irritated. That’s unbelievable, but it’s your ego. So you bring the person a cup of tea and begrudgingly dump it down, “Here’s your tea,” but even though you brought the person some tea, because you did it with selfishness buzzing in your heart, it’s negative. On the other hand, if you give somebody a cup of tea with the dedicated thought of bodhicitta, it’s the most positive thing you can do: all the wonderful qualities of the omniscient enlightened mind come from concern for other beings’ pleasure.

Just having this understanding is very powerful. For a start—forget about enlightenment—it makes your everyday life happy; you have no problems with those around you. It’s extremely practical. Therefore, as much as you can, train your mind in bodhicitta and try to realize that attachment is the greatest obstacle to the happiness of your daily life. And even if you can’t completely change attachment to your own pleasure to concern for that of others, at least you can try to practice the equilibrium meditation,8 which is also a very powerful and practical way of bringing enjoyment into your life.

Perhaps, instead of arrogantly going for the realization of enlightenment, you can first try to make your daily life joyful by putting a stop to the things that come from the selfish thought and complicate everything. For beginners, this is probably more realistic and sensible. Just look at your everyday life and see how selfish attachment causes all the problems that arise.

All the problems of desire come from attachment; all those due to hatred and anger also come from attachment. Even a bad reputation or the upset that arises when you’re insulted come from attachment. If you really understand this evolution you’ll have fewer problems and be psychologically healthy because understanding allows you to release emotional attachment so that it no longer has a hold on you.

What I’m saying is that sometimes we intellectualize too much about the highest goal—enlightenment—and neglect to investigate how our everyday problems arise. This only throws our life into disorder and is not a practical approach.

What’s practical is to check how everyday problems arise. That’s the most important thing and that’s what practicing Dharma means. By constantly checking what kind of mind causes our problems, we’re always learning. By understanding the nature of attachment we can easily recognize it when it arises. If you don’t know how to look, you’ll never see.

I don’t need to say much more now but if you have any questions I’ll try to answer them.

Q. Say we have the Mahayana thought and want to bring pleasure to others. There are so many of them—how do we decide who to help and how?

Lama. When I say that we should be more concerned for others’ pleasure than our own, I don’t mean that you literally have to help all beings right now. Of course, that’s impossible—that’s the point we have to understand. When you generate the wish to help infinite other beings and then look more deeply into what’s involved in doing so, you’ll see that at the moment, your mind, wisdom and actions are too limited to help all living beings and that in order to do so you’ll need to develop the infinite, transcendental knowledge-wisdom of a buddha. When you become a buddha you can manifest in billions of different aspects in order to reach and communicate with all the different sentient beings in their own language according to their level of mind. So, understanding that you can’t do this now but that you do have the potential to reach enlightenment and then really help them, you start to practice your yana until it eventually carries you all the way to buddhahood, when you can be of true benefit to others. However, this doesn’t mean you can’t be of some help to others now, even though it’s limited.

The path to enlightenment has three main levels. The first leads us to upper rebirths but not out of cyclic existence; from here, the help we can give others is minimal. The second level is for those who seek complete liberation from cyclic existence mainly out of concern for their own problems. Even though such practitioners transcend their ego, the help they can give others is still quite limited; they can’t help all mother sentient beings. Only fully enlightened beings can help all sentient beings—if that’s what you want to do, that’s the goal you have to reach, and that’s where the third, or highest, level of the path leads.

Helping others has to be understood as rather more than, “I want to share my furniture with others” and then sawing it up into little pieces and distributing them evenly among your friends. That’s not the way to help others. The emphasis has to be on training the mind. Otherwise it sounds a bit like communist propaganda: I have to share everything I own with everybody else. That’s wrong; it’s emotional. The communist idea of equality is false because it’s not based on mind training. It’s just another ego trip. It’s impossible to achieve true equality just by saying, “Everybody should be equal,” with ego, attachment and no mind training. You can’t control people’s minds with guns—from the outside it might look like control, but it’s not.

The goal is to change self-attachment to concern for others. This is based on equilibrium, which is achieved through meditation, not physically. It’s psychological, mind training, and very different from the communist idea of equality. Look at the Soviet Union, for example. Their original goal was equality but now they’re becoming more and more like America. Why? Because they have attachment; everybody wants to be happy. It’s the same with China. The cyclic nature of samsara is reality. The same things come around again and again. I’m not making some kind of telepathic prediction; you can see through logical analysis how it works.

Q. In thinking about the two vehicles, it seems that the Hinayana is quite strict in prohibiting certain actions—not killing, stealing, engaging in sexual misconduct and so forth—whereas the Mahayana says motivation is more important than action. Also, Nagarjuna quoted the Buddha as saying, out of his great compassion, that we should have few possessions and be content because it’s very difficult for us to know our motivation. So it would seem to me that at our level we should follow the Hinayana, not the Mahayana.

Lama. I agree that it’s better to have fewer possessions rather than to be surrounded by hundreds of objects of desire, pulling us this way and that and agitating our mind. However, Tibetan Buddhism puts Hinayana and Mahayana together; it unifies the two vehicles. Since our mind tends to run wild like a mad elephant, we definitely need to adhere to certain mental rules—following the disciplines suggested by experienced practitioners makes it unbelievably easier to practice sincerely and meditate properly.

For example, say you’re at a busy airport with people rushing everywhere and I tell you, “Meditate! Meditate!” It’s impossible, isn’t it? Why? Because all your sense doors are wide open and you just can’t focus your mind on one point. Similarly, if you sit down to meditate and I poke you with a needle, saying, “Concentrate! Concentrate!” you can’t do it. Objects of sense gravitation attachment9 are just like a needle—they automatically agitate your mind and by not avoiding them you make meditation difficult for yourself.

One lama said, “The more you possess the greater your superstition.” It’s true; the more possessions we have the more paranoid we are about protecting them and their constant presence in our mind causes it to be restless all the time.

In America, it’s almost a right to possess a big house, a couple of cars, a refrigerator and all kinds of other stuff. Nobody looks at you twice and it doesn’t necessarily take much effort to acquire such things. What takes effort is deciding, for example, what to have for breakfast; you have so many choices—“What should I eat? This? This? This? This? What about this?” It’s such a waste of time; that kind of thing makes life difficult.

Take the middle path and choose your environment carefully; create your own mandala, just like Chenrezig creates his—surround yourself with people and things conducive to your practice. Sometimes we’re very weak; we think everything’s so difficult. However, you have to know that human problems can be solved by human wisdom. So create your own mandala according to the way in which you want to develop—select carefully the kind of people with whom you want to associate, the kind of house in which you want to live, the activities in which you engage and so forth. That’s very important. Otherwise you’re just left with “Whatever happens happens. Who knows?” That’s not the right approach. Karma is strong. Just because you want something to work out in a certain way doesn’t mean it will go the way you want but if you put yourself into the right environment, you give yourself every opportunity to develop the way you’d like.

Q. Thinking about all this creates a bit of a dilemma for me. In a land of excess like America, it would seem that the fewer possessions I have the less my attachment and the greater my ability to think clearly and therefore benefit others. On the other hand, if I had a nice big house with lots of bedrooms perhaps I could help people more by giving them a good place to live, food to eat and the opportunity to meditate while being supported in this way.

Lama. If you have skillful wisdom it’s definitely possible that you could help others like that, but if your mind is unclear and you make your offer emotionally, ten days later you’re going to be saying, “The kitchen’s a mess, there’s a broken window, last night he did this, today she did that….” You get upset; others get upset—unfortunately, things can turn out like that. If you can execute your plan with wisdom and keep it all together skillfully, then of course helping others in the way you suggest would be a great thing to do, but first think it through and weigh your options carefully.

Getting back to the issue of mental rules, however, it’s important to follow them at the outset of your practice but after some time, if you have skillful wisdom, perhaps you don’t need them any more.

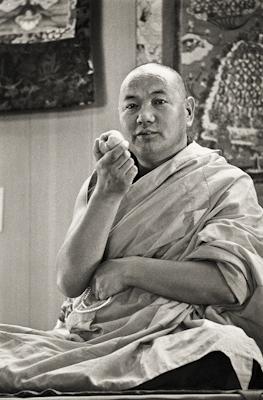

Q. I’m wondering how others and I should relate to you as a lama. Should we think of you as a person too?

Lama. Of course! I’m just another man.

Q. I mean, it’s very hot outside today and although it’s OK for me, I understand that it might be bad for you.10 Since you’re a lama, am I allowed to think in that way? Somebody told me that we should never think of a lama as an ordinary person.

Lama. Of course I’m a person. At the moment I’m manifesting as an American man from Wisconsin!

Q. Lama, where do you draw the line between putting yourself into situations—for instance, a job—where you have many opportunities to see your self-cherishing but where unconsciously you’re also creating a lot of negative karma, and not putting yourself into situations where the negative mind can easily arise like this?

Lama. That depends. For example, if you don’t put yourself into that kind of situation perhaps you won’t have any money to sustain your life. Say you can’t get a job other than one that will disturb your mind. You can take it and try to use that opportunity to understand your mental disturbances and in that way develop wisdom. It’s a mixed situation, part negative and part positive. If you have little choice other than to take that job, then you’ve got to try to make the positives outweigh the negatives, but if you think that that is beyond your capabilities and will just lead to a nervous breakdown, then obviously it’s better to try to find some other kind of work. You have to assess all this for yourself. However, if you’re skillful, you’ll try to find a Dharma job that offers peace and happiness and the opportunity to benefit others.

Q. My present job is driving a cab, so there are all sorts of people getting into the car all day long and I have many opportunities to practice the equilibrium meditation, but what I was asking was, is that type of situation good, where there’s all this material to reflect on during my meditation at night but at the same time I’m creating a lot of negative karma during the day, getting angry, for example?

Lama. Again, it depends. If you assess the situation as basically more positive, then a little anger might be OK. Developing yourself for the benefit of others is better than a little anger. You can think, “My anger makes me go a bit crazy but as long as I’m helping others, I don’t care.” Giving yourself up for the sake of others automatically makes your craziness disappear.

Thank you. I think that’s all the questions we have time for. We should now dedicate our merit. Dedication is very important. We often do positive things without dedicating the merit and as a result, as soon as we get angry that merit is destroyed. It’s all about mental energy. So whenever you do something worthwhile, instead of puffing up with pride—“I did great”—or at some point getting angry, all of which dissipates your positive energy, sincerely dedicate your merit to others. This is an essential part of mind training. So beginning with bodhicitta, the determination to lead all mother sentient beings to enlightenment, do whatever action it is you’re doing and then dedicate your merit: this helps make the action complete.

If we’re not aware of these three—motivation, action and dedication—all our actions are incomplete and therefore not particularly powerful. On the other hand, when we do negative actions, even without thinking, we do them perfectly from beginning to end: we’re motivated by strong desire, we do the action with great enthusiasm, and when we finish we think, “That was so good,” sort of dedicating it to attachment. So from beginning to end it becomes a perfect negative action.

Mahayana practice is the complete antidote to perfect negative actions. At the beginning we generate bodhicitta, which completely neutralizes self-cherishing. Then we engage in a positive action. Finally, instead of feeling proud, we sincerely dedicate the merits of that to others. In that way it becomes totally positive.

Other religions may not be complete in the same way. They might start with good motivation but be bad in the middle, or the middle might be OK, but there’s no dedication. Such incomplete practices can’t be proper antidotes to attachment. If you look at the psychology of the Mahayana you’ll see that the entire practice—motivation, action, dedication—is geared toward the destruction of attachment. You have to understand the psychology of your practice in order to know the purpose of what you’re doing.

Notes

6 In the Tibetan Tradition of Mental Development, Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey says (p. 202), “The Mahayana is called ‘great’ for the following reasons: 1. The aim is great, because it is for the benefit of all sentient beings. 2. The purpose is great, for it leads to the omniscient state. 3. The effort is great. 4. The ultimate goal is great, because it is buddhahood rather than mere freedom from samsara. 5. The concern is great, as it is for all sentient beings. 6. The enthusiasm is great, as the practice is not regarded as a hardship.” [Return to text]

7 In Lama Tsongkhapa’s Foundation of All Good Qualities. See www.LamaYeshe.com. [Return to text]

8 See the Appendix in Lama Yeshe’s Ego, Attachment and Liberation (a free book from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive). [Return to text]

9 Editor: For several years I thought Lama was trying to say “sense gratification attachment” and would try to correct him (to no avail) but eventually it became clear that he knew what he was saying and meant the irresistible gravitational pull that objects of attachment have upon our mind. [Return to text]

10 It was common knowledge among Lama’s students that he had a heart condition that was aggravated by hot weather even though he never complained himself. [Return to text]