Meditation on the breath

Sit comfortably on your meditation cushion or your chair. Adopt the meditation posture and focus all your attention on your breath, going out and coming in through your nostrils. Breathe naturally, but concentrate fully on your breath. Remember, when doing this meditation, if distractions arise, or, rather, when distractions arise, try to be aware of their arising as soon as possible. As I said before, this kind of placement, or mindfulness, meditation involves two mental factors. The main part of your mind is focused on your breath; ninety to ninety-five percent of your mind is focused on your breath—mindfulness, remembrance; remembering what it is that you are supposed to be focused on, your breath.

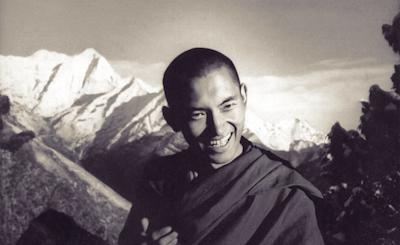

Then, a small corner of your mind acts like a sentry. That’s watchful alertness, waiting, like a sentry, for distraction to arise, and its function is immediately to deflect the distraction before it really comes to the attention of the main part of your mind, which should remain focused on your breath. Lama Yeshe always used to say that distractions don’t arrive all of a sudden, unannounced. They’re heralded by a kind of preceding vibration, just as the sun itself doesn’t rise out of a pitch-black sky but is preceded by the light of dawn, that lets us know it’s coming. Therefore, success in deflecting distractions before they distract depends on your recognizing the warning signs and acting upon them.

However, should this not work and you become distracted by some kind of interesting thought, pain or whatever it is, as soon as you notice that you have become distracted, that your mind has gone off the breath, drop the distraction immediately and just come straight back to the breath. Don’t get involved in thinking about the distraction, don’t beat yourself up for having become distracted, “Oh, I’m a terrible meditator; I’ll never be able to concentrate,” don’t do anything like that; just come straight back to the breath.

So again, press the pause button on your CD player, meditate on your breath for a few minutes, and when you are ready to resume, press the play button.

Motivation

Now generate the right motivation, a positive motivation for studying the topics of this session, for studying this module on death and rebirth, for taking the entire Discovering Buddhism course, and for practicing Dharma in general. Think, “The purpose of my life is to lead all sentient beings out of suffering and into the everlasting happiness of enlightenment. In order to do this, first I must attain enlightenment myself. In order to do this, I have to study and practice the entire graduated path to enlightenment. Therefore, as part of that, I am studying the teachings on death and rebirth.”

By setting your mind, by setting your motivation in this way, you automatically override, or displace, any negative motivation that might have been in your mind, any motivation that has to do with the comfort of this life, any attachment that might have been there. And having generated this positive, or bodhicitta, motivation, it pervades your entire session; you don’t have to keep motivating every few minutes for the next hour or so. This initial motivation encompasses the entire session, until, at the end, you again dedicate the vast accumulation of merit that you have generated through having set this motivation and then studied an appropriate topic.

Recapitulation

In this session, we’re mainly going to look at the six disadvantages of not remembering impermanence and death and the six advantages of doing so. First, however, I just want to recap what we’ve done and again place impermanence and death in the context of the entire lamrim, the graduated path to enlightenment.

In the first couple of sessions, we looked at the mind and life and death in general; we talked quite a bit about impermanence; then we discussed the importance of this teaching and the purpose of studying it; and we also talked a little about fear and the benefits of positive fear. Also by now, you should have practiced the first meditation on the meditation CD: the meditation on the continuity of consciousness and the analytical meditation on aspects of impermanence.

The outline of the lamrim, of the commentary on the steps of the path to enlightenment, has as its first main topic, generating devotion to the spiritual teacher. Then it goes on to explain what to do once we’ve generated such devotion.

The first thing we need to do after that is to persuade, or convince, or encourage, ourselves to extract the essence from this perfect human rebirth that we’ve received. We do this by recognizing what the perfect human rebirth is, with its eight freedoms and ten richnesses; we contemplate the great usefulness of the perfect human rebirth; and think about how rare it is to receive and how difficult it will be to find again.

Having become convinced, we then have to understand how to extract the essence from this perfect human rebirth. That leads us into the three scopes of practice that I’ve mentioned more than once before: the small, intermediate and great scopes, the path of the practitioner of least intelligence, the path of the practitioner of medium intelligence and the path of the practitioner of great intelligence.

Now, as we’ve already understood, even though we want to follow the path of the practitioner of great intelligence—we want to develop loving kindness and compassion for all sentient beings and on that basis generate bodhicitta—still, we have to study and practice the paths of the practitioners of least and medium intelligence.

Looking at the first of these, the small scope, first we have to develop the mind that strives for a better rebirth. The aim of the small scope is to avoid rebirth in the three lower realms, in other words, to gain rebirth in the three upper realms. The beginning of developing such a mind is to remember that this life does not last long and that we will die. This module on death and rebirth is just a very simple introduction to the topic, and what you really need to do is study in depth and practice what I’d say are probably the two main references for this subject—not just for this subject but for the entire lamrim—and they are Lama Tsongkhapa’s Lamrim Chenmo, which has been published in English as the Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment, and Pabongka Rinpoche’s Liberation in the Palm of your Hand. Both of these texts have very clear explanations of impermanence and death and are an excellent reference for meditation on these topics. Their approaches are slightly different, for example, the Lamrim Chenmo approaches mindfulness and death, the contemplation that you will not remain long in this world, in four parts: the faults of not cultivating mindfulness of death; the benefits of such cultivation; the kind of mindfulness of death you should develop; and how to cultivate mindfulness of death.

Liberation in the Palm of your Hand puts it under three main subheadings: the six disadvantages of not remembering death; the six advantages of remembering death; and the actual way of remembering death. The last one is divided into two sections, one which I mentioned in the last session—the three roots, the nine reasons and the three determinations, and we’ll get into those in the next session—and the other, meditation on the aspects of death.

So, I think you should definitely buy and study those two books in conjunction with what I am saying here…not only for the purposes of this module and the Discovering Buddhism course but as a basis for living your entire life in the Dharma. Without exaggeration, these two classic lamrim texts are enough to serve as a foundation for your whole being.

The disadvantages of not remembering impermanence and death

Now we are going to look at the six disadvantages of not remembering impermanence and death.

1. The first is the disadvantage of not remembering Dharma. Lama Tsongkhapa said that there are four mistakes we make that prevent us from taking full advantage of our perfect human rebirth. These are, conceiving

(a) The impure to be pure;

(b) Suffering to be happiness;

(c) The impermanent to be permanent; and

(d) The selfless to have a self.

These misconceptions prevent us from practicing Dharma and initially, it’s the conception of the impermanent to be permanent that is the main source of injury to ourselves. If we don’t remember that this life is short, is going to end and is finishing all the time, instead of putting effort into practicing Dharma, we’ll expend more energy in taking care of our worldly life. We’ll put effort into studying mundane subjects so that we can get some kind of worldly degree, some kind of worldly qualification that will enable us to get some kind of worldly job, so that we can have money in order to buy not only the things that we need to survive—food, clothing, shelter and medicine—but also things for our worldly, or samsaric, enjoyment: better food, better, more fashionable, clothing, better housing, better cars…more and better everything; in general, much more than we need to survive; more than our share. With so much of the world’s population—which is, by the way, wildly out of control—in so much need, it’s disgraceful the amount we consume. But worse is the way we focus on excess and never find enough time to practice Dharma.

2. Second, there’s the disadvantage of remembering to practice Dharma—or, remembering that we should be practicing Dharma—but putting it off, procrastinating, postponing the practice. The greatest interference to practicing Dharma is the thought that resides in our mind all the time, not necessarily consciously but somewhere in our mind it’s there: “I won’t die today.”

Lama Tsongkhapa said,23

Everyone has the idea that death will come later, at the end. However, with each passing day people think, “I will not die today; I will not die today,” clinging to this thought until the moment of death. If you are obstructed by such an attitude and do not bring its remedy to mind, you will continue to think that you will remain in this life.

This thought that we won’t die today prevents us from practicing Dharma today and causes us to put it off until tomorrow, the next day and beyond. Of course, we’re right most of the time, and that every day that we’ve thought “I’m not going to die today” up until now we haven’t died today, but still, it’s not the right way to think. It’s much better to think “I’ll die today” as soon as we get up in the morning. This can only help us because it forces us to discriminate between what’s really important and what’s not. Again, we have to remember what the Buddha said, that it’s uncertain which will come next, tomorrow or the next life, and that since tomorrow is uncertain but the next life is definite, we should pay more attention, should focus more energy on, preparing for the next life than for tomorrow.

Procrastination is a form of laziness. There are three types of laziness and the first two arise from just this lack of awareness of impermanence and death. The first form of laziness is this laziness of procrastination, constantly putting things off until tomorrow, especially the practice of Dharma. Perhaps we should call this practicing the mañana, the lazy vehicle. I remember Lama Zopa Rinpoche once talking about how fortune tellers always seem to tell you good stuff that you want to hear but that he’d rather have someone read his palm and say, “Oh my God! You’re going to die tomorrow and go to hell,” because this would give him the energy to intensify his practice—as if he needed it.

Second is the paradoxical laziness of being busy, where we busy ourselves with samsaric work, with all kinds of worldly pursuits, kidding ourselves that we so industrious, so busy doing all these important things that we don’t have time to practice Dharma at the moment but will have time for it later. From the Dharma point of view, this is a form of laziness, a giving in to attachment and a failure to appreciate how precious life is for doing what’s really meaningful—practicing Dharma in order to obtain better future lives, liberation and enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings.

For the record, the third form of laziness, which is not directly related to impermanence and death, is the laziness of delusions of incapability: “It’s too hard to practice Dharma; it’s too hard to overcome attachment; I’m not good enough to develop perfect concentration; I’ll never realize emptiness.” Actually, all these deluded thoughts can be overcome to a large extent by meditation on the perfect human rebirth, which actually precedes the meditation on impermanence and death, and if we follow the normal set-up of the lamrim in our practice, by the time we’ve accomplished the meditation on impermanence and death, we should pretty much have defeated laziness altogether.

3. The third disadvantage of not remembering impermanence and death is that we might remember to practice but the Dharma practice we do becomes impure, polluted, tainted by attachment, defiled by preoccupation with what are called the eight worldly dharmas, or eight worldly concerns. These eight are four pairs of opposites:

(a) Being happy when getting material things and unhappy when not;

(b) Being happy when experiencing pleasure and unhappy when not;

(c) Being happy with fame and a good reputation and unhappy with notoriety and a bad reputation; and

(d) Being happy when praised and unhappy when criticized.

These eight worldly concerns prevent our mind from remaining on an even keel. When we get something nice, our mind goes up; when we don’t, our mind goes down. We’re happy when someone gives us a present and unhappy when we’re forgotten, jealous when somebody gets something that we wanted.

When things are going well, our mood goes up; we feel happy. When things go badly or we feel sick, our mind goes down; we feel depressed and incapable of doing anything.

When we hear people speaking well of us, our mind swells with pride, inflated, like a balloon. We think, “Yes, I am good; other people think I’m good.” It’s so important for other people to think well of us. We are so attached to having a good reputation. When we are spoken of badly, when we hear ourselves being denigrated, we get upset, unhappy and angry, and lash out at those who speak badly about us.

When we are praised, when someone says, “Oh, you did a good job, you’re really wonderful, you’re an inspiration; you’re this, you’re that, you’re the best,” again, our minds go up. When we are criticized, “You’re wrong, you made a mistake, you’re a fool,” we get unhappy again.

Thus, our life is a roller coaster of emotions; we’re imprisoned by these eight worldly dharmas, and they all come from attachment to the happiness of this life. We’re so used to living under the control of the eight worldly dharmas that even when we remember to practice Dharma and don’t procrastinate, when we try to practice right now, our practice is poisoned by attachment, made impure by what Lama Zopa Rinpoche calls the evil thought of the eight worldly dharmas.

Some people might become even monks or nuns in order to receive food, clothing and offerings from others; to have what they consider to be a materially easy life. Some people might see teachers being given gifts by their students and showered with all kinds of positive attention and decide to study Dharma in order to become a teacher to receive such benefits. People might study Dharma in order to become famous or well known as a teacher or to have people come up to them and praise them, “Oh, thank you for your teaching, it was so wonderful; you have such great knowledge.”

If any of this kind of motivation creeps into your practice, it’s like a small vial of potent toxin poured into a large body of water; the whole thing becomes poisoned. The great Atisha said,24

Ask me what the results of thinking only about this life are and I will tell you: they are merely the results of this life. Ask me what will happen in your next lives and I will tell you: you will be reborn in hell, as a hungry ghost or an animal.

Even though an action might look like you’re practicing Dharma, if your motivation is one of simply wanting the happiness of this life, the whole action becomes negative and the cause of suffering.

There’s that quite well known story of Dromtönpa, Atisha’s main disciple, seeing a man circumambulating a stupa and saying to him, “Circumambulating stupas is all well and good, but wouldn’t it better if you practiced Dharma?” Even though the man’s circumambulating the stupa looked like a religious action, a Dharma action, the bodhisattva Dromtönpa, who was, in reality, the Buddha of Compassion, Avalokiteshvara, suggested that he’d be better off practicing Dharma.

We can circumambulate stupas for all the wrong reasons. If you go to Boudhanath, in Nepal, you’ll see hundreds of people circumambulating the great stupa there every day, but are they really practicing Dharma? That’s the question. Of course, just looking from the outside at what somebody’s doing, just looking at somebody’s external actions, you can’t really tell if they are practicing Dharma or not, because actual Dharma practice is in the mind and depends principally upon the practitioner’s motivation. Many times we might decide to circumambulate the great stupa at Boudhanath just to see who else is there, to catch up with friends; or we might be circumambulating the stupa but paying more attention to what’s in the shops around the stupa; or we might be circumambulating the stupa so that others will see us and will think, “Oh, what a devoted practitioner; look at him circumambulating the stupa.” We might make prostrations to the stupa and think, “I hope people see me doing these prostrations; don’t I make great prostrations! Look how I make them perfectly according to how they’re supposed to be done, as explained in the texts. I hope other people see me and think how good I am at prostrating.” All sorts of negative motivation can creep into our practice and completely ruin it.

So, in the story, after Dromtönpa said to the man that circumambulating stupas was all well and good but wouldn’t it be better to practice Dharma, the man thought, “Well, if circumambulating stupas isn’t practicing Dharma, perhaps he means that I should be reciting texts.” So the next time Dromtönpa saw him, the man was sitting at the stupa, piously rocking backwards and forwards reciting texts, and again Dromtönpa said to him, “Reciting texts is all well and good, but wouldn’t it better if you practiced Dharma?”

Again, if you go to Tibet or Nepal, perhaps Dharamsala, you’ll see monks or lay people reciting texts in public with their hat out. So if they’re just out there reciting texts to get money for food and clothing, then it’s a worldly action, the cause of suffering. Of course, because of the power of holy objects—the power of stupas, the power of texts—there is definitely some blessing to be received by circumambulating or reciting, but if the motivation is simply a worldly one, then the whole action is really polluted. The thing is, it’s OK to accept money for reciting texts—we all have to eat—but the motivation should be, “I don’t care if I get money or not; I’m reciting this text in order to receive enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings.” It all depends on motivation.

So then the man thought, “Well, if reciting texts isn’t practicing Dharma, perhaps he means that I should meditate,” and the next time Dromtönpa saw the man, he was sitting in meditation. Well, we can also meditate for the wrong reasons. We can sit up meditating very nicely in our seven-point posture, with our back so straight and our eyes slightly open, like really good meditators are supposed to do, and think, “Oh, I bet people think I am great meditator. Look at me sitting here with a straight back and my eyes slightly open just like the Buddha; people are going to think I’m really good.” Again, this kind of motivation creeps in, uninvited but insistent, and it’s because we are so familiar with negative motivation, which arises automatically, and so unfamiliar with positive motivation, which can only be generated with conscious effort and exertion.

Meditation means making the mind familiar with positive objects, and in order to make our minds more naturally positive than negative, we have to meditate a great deal on positive objects. This starts by our consciously generating, as we do at the beginning of our sessions here, a positive motivation.

Anyway, once more, Dromtönpa said to this man, “Meditating is all well and good, but wouldn’t it be better if you practiced Dharma?” So then the guy really lost it, got very exasperated, and said, “Practice Dharma! Practice Dharma! What the hell do you mean, ‘Practice Dharma’?” Then Dromtönpa replied, “Renounce this life.”

So what he meant was, give up attachment to this life. He didn’t mean renounce this life by dying. We’ve renounced this life in that way countless times since beginningless time and we’re still in samsara, we’re still in cyclic existence, we’re still not Dharma practitioners. So “renounce this life” doesn’t mean go shoot yourself in the head; it means give up attachment to the happiness of this life. Therefore, you can’t judge the positivity or negativity of an action from its external appearance alone. You could be walking down the street by yourself and have a beggar approach you for money and tell that person roughly to go away, but on another occasion you might be walking down the street with someone you want to impress, and when a beggar asks you for money you give generously. That’s just giving to your ego; that’s just giving to enhance your worldly reputation, for others to think well of you. It’s not giving to benefit the other person; it’s giving to benefit yourself.

All these actions that we tend to think are Dharma—circumambulating, prostrating, reading texts, meditating, giving gifts—must be done with the motivation of reaching enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings. Actually, if you generate pure motivation, it’s natural that the worldly results will come of their own accord, which is why His Holiness the Dalai Lama talks about wise selfishness; he says if you’re going to be selfish, be smart about it.

What is selfishness? It’s wanting the best for yourself. Therefore, His Holiness says, if you want the best for yourself, if you want to be selfish, forget about yourself and totally devote your life to the happiness and welfare of others. The result of this will be that everything positive, up to enlightenment itself, will come to you. The more you cherish others, the less you cherish yourself, the quicker you’ll obtain the supreme state of enlightenment, and there is no greater benefit than that.

I remember after my first Kopan meditation course feeling that I really wanted to put my whole life into practicing Dharma but didn’t know how I’d be able to support myself. I said to one of the senior students, “You know, I really want to put my life into Dharma, but what will I do to generate an income? I don’t have that much money.” So she said, “Oh, if you give yourself to the Dharma, the Dharma will always look after you.”

This was a very important thing for me to hear, because I then decided, “OK, I’ll try it.” Now, I don’t really know how much I’ve given myself to the Dharma, but for more than thirty years now I’ve devoted myself to working for Lama Yeshe’s and Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s organization, and I’ve certainly been looked after in terms of receiving the things one needs to survive. Thus, from the point of view of my own experience, the Dharma really does work in that way. I can’t say, of course, that I’ve had pure motivation or anything like that, but in my case, just the attempt seems to have been enough, and if anybody else is so inclined, I can strongly recommend making the Dharma the main thing in your life.

Anyway, sometimes people think, “If I devote myself to the Dharma and don’t devote myself to earning an income, maybe I’ll go broke; maybe I’ll even die.” To counter such thoughts, we have what are called the ten innermost jewels of the Kadampas. Remember from our first session, Atisha’s followers were called Kadampas, and their ten most closely guarded possessions were 25

(a) Ignoring this life and devoting oneself wholeheartedly to the Dharma;

(b) Being prepared to become a pauper;

(c) Being prepared to die a pauper;

(d) Being prepared to die alone with no one to take care of one’s body;

(e) Being determined to practice Dharma, regardless of reputation;

(f) Being determined to keep all vows purely;

(g) Being determined to avoid discouragement;

(h) Being prepared to be an outcast;

(i) Accepting the lowest status;

(j) Attaining exalted buddhahood as a result of successful practice.

These thoughts and principles can guide our life and are based on constant recollection of impermanence and death and a clear discrimination between what’s Dharma and worthwhile and what’s not Dharma and therefore not worthwhile.

As Pabongka Rinpoche says,26

…make up your mind to ignore the eight worldly concerns, and you will receive this life’s comforts, happiness and fame as if you have courted them. So, if you yearn for the eight worldly concerns, you are a worldly person; if you ignore this life, you are a Dharma practitioner. Geshe Potowa asked Dromtönpa, “What is the fine dividing line between Dharma and non-Dharma?” Drom replied, “It is Dharma if it becomes an antidote to delusions; it is non-Dharma if it does not. If all worldly people do not agree with it, it is Dharma; if they do, it is not Dharma.”

The point here is that Dharma and worldly concerns are opposites and we should turn our back on worldly concern and devote ourselves fully to the Dharma, and, in case you’ve forgotten, all this is to do with the third disadvantage of not remembering impermanence and death, and how through not remembering, our practice of Dharma becomes impure.

4. The fourth disadvantage of not remembering impermanence and death is the disadvantage of remembering to practice Dharma but not practicing seriously or continuously; we’re unable to persevere in our practice and get easily distracted. We start off doing some practice—meditating, prostrating, studying and so forth—but soon get bored with it and leave it to do something we find more interesting, something worldly.

There was a geshe who had decided to spend the rest of his life meditating in a cave, and there was a thorn bush growing outside the cave in which he’d decided to spend the rest of his life. So every time he went out of the cave or went back in, the thorn bush would tear his clothes or scratch his skin. As the years went by, the thorn bush got bigger and bigger, obstructing the entrance to his cave more and more, and each time he went out and got scratched, he’d think, “I really ought to do something about that bush.” But then he’d think, “No. Life is impermanent and can finish any time, and there’s no guarantee that I’ll live long enough to return to my cave, so why waste time cutting this bush?” Then, when it came time for him to go back in, it would be the same thing. “Oh, I should really trim that bush. But life is short and can finish any time and there’s no guarantee that I’ll ever leave this cave again, so why should I waste my time cutting the bush?” In that way, his life passed, he spent more time in Dharma practice and none in cutting the bush, and he attained many realizations. We can apply this geshe’s experience to our own life and use our time less in extraneous activity and more in Dharma practice.

5. The fifth disadvantage of not remembering impermanence and death is that we make no effort to control our negative mind and easily create negative karma. When attachment arises to an object or another person, we should think, “Attachment is a negative mind. If I follow attachment I am going to leave a negative imprint on my consciousness, which can only lead to rebirth in the lower realms and other experiences of suffering. Therefore, since I can die at any moment, I should definitely not follow this attachment. There are enough imprints of attachment on my consciousness; I’ve already created enough negative karma in this and previous lives, why create more, especially since I’m going to die soon? If I die with more negative imprints on my consciousness, there’s no way that I’ll get a better rebirth; no way that I’ll be able to continue practicing Dharma in future lives; no way that I’ll be able to escape from samsara and attain liberation and enlightenment.” So by remembering impermanence and death in that way, you should stop yourself from creating the negative karma of attachment.

Similarly, when you get angry or see anger beginning to arise in your mind, you should again think, “This is terrible. Anger is one of the worst kinds of negative mind. If I die with the imprints of anger on my consciousness, I’ll reborn in hell, and since death can occur at any moment, the last thing I need is another angry imprint on my consciousness.” In that way, you can again protect yourself from the negative imprints of anger, pride, jealousy and all the other kinds of negative mind.

If you don’t remember impermanence and death, if you just let yourself go, thinking, “Oh, my life is long; there’s always the chance to purify, to do a three-month Vajrasattva retreat.” But of course, that time never comes, because you keep postponing your practice. “I’ll do it next year, I’ll do it next year, this year I have to do this and that.” Or you might think, “If I take time off to do retreat I might lose my job and then how will I earn a living?”

So there’s always this idea that we’re going to live for a long time, that we’re not going to die soon, and therefore, we constantly give in to attachment, anger and the other negative minds. So this is yet another shortcoming of not remembering impermanence and death: we allow ourselves to create more and more negative karma.

6. Then finally, the sixth disadvantage of not remembering impermanence and death is that when we do die, we die with much worry and regret.

Let me read you something that Lama Zopa Rinpoche said about this.27

If you don’t practice the good heart, loving kindness, compassion or bodhicitta, you finish up living with only delusions, attachment, anger, and so forth in a world of hallucination. It’s as if you’re asleep from birth to death, never seeing the reality of life. Then, all of a sudden, death comes. The day when you see yourself dying, your life has gone. There’s no longer any time to meditate, to develop the mind in the path. At that moment you see your life as incredibly short; you see the reality of life, its impermanent nature, but no matter how much fear you have, there’s no time to practice anything.

I’ve heard people say that at the time of death your life flashes before your eyes. All the negative things you’ve done come into your mind: the harm you’ve given to others, the ten non-virtuous actions you committed, and so forth. Then you feel great regret and fear.

Even people who don’t accept reincarnation, either intellectually or as a result of the teachings of another religion, feel afraid at the time of death. Your heart tells you that something horrible is going to happen and you have terrifying visions. Instead of going to the next life with incredible joy, peace and happiness, you go with great fear and terror. Instead of being reborn in a pure land, where even the word “suffering” does not exist, you get reborn in the three lower realms, where there’s barely a single happiness. This is what happens if you don’t practice Dharma during your life.

Pabongka Rinpoche describes this as being confronted by an enemy called “dying without having practiced Dharma.”28 That is the name of the enemy who confronts us at the time of death, the enemy called “dying without having practiced Dharma.” That’s when we see that all the wealth we’ve accumulated, our power, our position, our family, our friends, even our most cherished body, all these things we put all our life’s energy into, are of no use whatsoever. Far from helping us at this most important time of life, our death, these things turn into enemies; they harm us. Great attachment to them arises, as does the great sorrow that we have to leave them behind. And worst of all, strong regret for opportunities missed, the Dharma that we didn’t practice.

Our problem is that we’re afraid of death, therefore, we don’t think about it; therefore, we deny it; we ignore it; we push it out of our mind; we pretend that it doesn’t exist. Then, when death comes, as it inevitably must, we feel afraid; very afraid. What we should do with our fear of death is use it constructively, use it to understand death, use it to prepare for death. Then, when death comes, we won’t be afraid; we’ll die in a happy frame of mind. So, not remembering impermanence and death brings this sixth disadvantage of dying with much worry and regret.

Meditation

We’ve now come to the end of this session. I thought we’d also be able to cover the six advantages of remembering impermanence and death here, but since we’ve run out of time, we’ll deal with them next time. Meanwhile, before going on to the fourth session, please go to the meditation CD and do Meditation 2, which covers both the six disadvantages of not remembering impermanence and death and the six advantages of doing so.

Dedication

Finally, let’s dedicate the merit that we’ve created in this last session. We began by meditating on the breath and generating that most positive of motivations, bodhicitta. Then we recapped the place of impermanence and death in the lamrim and considered the six disadvantages of not remembering impermanence and death. Therefore, all in all, we’ve created a great deal of merit and should dedicate this in harmony with our motivation by simply thinking, “Because of this merit, may all our Dharma teachers live long and healthy lives, may the holy Dharma spread throughout the ten directions, and may all sentient beings quickly reach enlightenment.”

Thank you very much.

23 Great Treatise, p. 145. [Return to text]

24 Quoted in Liberation, p. 334. [Return to text]

25 Liberation, p. 336 and p. 800, n. 36. [Return to text]

26 Liberation, p. 337. [Return to text]

27 From Lotus Arrow, newsletter of Kurukulla Center, Boston, June-August 2003. [Return to text]

28 Liberation, p. 339. [Return to text]

Sources for these publications can be found on the References page.