Since the inception of Liberation Prison Project, a social services project of the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition, FPMT’s spiritual director, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, has received letters from people in prison, mainly in the USA.

The work of the prison project, named by Rinpoche in 2000, began in 1996 with a letter to Mandala, the foundation’s magazine, from a twenty-year-old Mexican-American, Arturo Esquer, at Pelican Bay, a top-security prison in northern California where he was serving out his three twenty-five-years-to-life sentences. At the time he was in isolation in the Security Housing Unit, where he spent twenty-three hours a day locked in his cell. He wrote that in the SHU library’s list of available titles he’d found a book by Lama Yeshe, the co-founder with Rinpoche of the FPMT. He said that he was moved by Lama’s teachings on compassion and wanted to learn more. Mandala’s address was in the book.

He explained that he’d been in gangs on the streets of Los Angeles since he was eleven years old and in prison since he was thirteen, first as a juvenile and then tried and sentenced as an adult at the age of sixteen. He received Buddhist books and spiritual guidance from the prison project. Word spread, and within a year forty inmates around the country were communicating with the project.

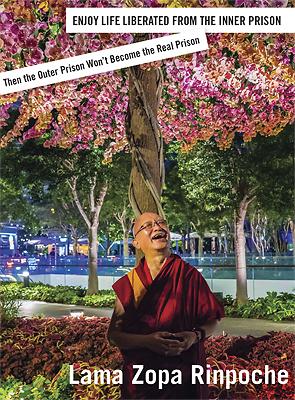

Many of the inmates, like Arturo, were serving long sentences and some were on death row. Some became serious practitioners and students of Buddhism, but all benefited from the friendship enjoy life liberated from the inner prison of mentors through the prison project—and continue to do so—often their only support.

Over the years Liberation Prison Project has helped some twenty thousand inmates, most in the USA, but also in other countries, including Australia, Italy, Spain, Mexico, Mongolia and New Zealand, where local projects have been established.

Some of the prisoners, inspired by the teachings in Rinpoche’s books or by what they’d read about him in the prison project newsletter, would write to Rinpoche personally—Arturo was the first to do so. Many requested him to be their spiritual teacher.

This book is a compilation of the one hundred-plus letters Rinpoche has written in response to the inmates over the years, integrated into a coherent narrative. Typically, he’d write three or four pages, but it was not uncommon for the letters to cover fifteen or twenty typed pages—one man received a letter of forty-five pages!

Rinpoche would spend a great deal of time dictating the letters, coming back to them again and again over many days, choosing carefully the most suitable practices and books for each person, finding creative ways to present the advice, and always encouraging them to never give up and to use their time in prison in the most beneficial way possible—always in terms of their spiritual growth.

All of Rinpoche’s advice is framed within the advanced levels of Mahayana Buddhism known as “mind transformation”—in Tibetan, lojong—the essential component of which is developing the brave attitude of welcoming the difficulties of life and interpreting them differently: seeing them as opportunities, advantages, not problems. Implicit in this approach to practice is the ultimate view of reality, that nothing has an intrinsic nature as pleasant or unpleasant, as this or that, which is the logical basis for our ability to see things differently.

Why would we want to see unpleasant experiences as good? Because, according to Buddha, contrary to our instinctive belief, the main cause of our suffering and happiness is not the thing itself—the person, the event, the place—but our interpretation of it.

We’re all driven by primordially deep attachment to getting only the nice things, addicted to the belief that they’re the source of happiness. The moment attachment is thwarted, the result is aversion and the various other disturbing emotions that ensue. And even when attachment does get what it wants, the pleasure doesn’t last, which again results in disappointment, anger, depression and the rest.

We thus spend our lives attempting to manipulate the outside world to make it just so, swinging hopelessly between the two extremes of happiness when the good things occur and unhappiness when they don’t.

On the face of it, learning to see being in prison as good makes no sense. But the approach is practical, not punitive or moralistic. Buddha says if we can change something, please change it.

But what if we can’t? This is the point at which the practice of lojong starts. And this is very much the situation for people serving long sentences in prison or on death row. They don’t have the luxury to change their situation. They can’t escape from prison.

But, as Rinpoche points out, they can escape from their inner prison—we all can—the prison of attachment, the prison of anger, the prison of the other disturbing and deluded states of mind that are the source of our suffering.

The result of this practice isn’t merely that we become less attached, less angry, less fearful, and therefore experience less suffering. It’s not passive. As a result of practice, just naturally we become more content, more courageous, more wise—in other words, we also experience more happiness. We stop being pulled from pillar to post by the vagaries of life. We become emotionally stable, fulfilled and, crucially, in charge of our internal lives.

And not only that. Just naturally, we become more open to others, more empathetic: we realize that we’re all in the same boat. Now, having helped oneself, we can help others.

The inmate’s environment, Rinpoche says, is a precious opportunity to develop this marvelous potential, which in the long term brings the achievement of their own buddhahood: the utter eradication from their mind of all delusions and the development to perfection of all wisdom, all goodness—the very meaning of the word “buddha.”

This internal work does not imply not acting to bring about external change, to fight for one’s freedom from prison, let’s say, or to help others in prison. You don’t become passive—on the contrary. Because you’re not overwhelmed by anger or despair, you’re capable of effective action. Arturo is a good example. As he developed his spiritual practice, he gave up his allegiance to gangs—the only world he’d known—got himself an education, and when the rules in California changed to allow inmates who, as juveniles, had been sentenced as adults the opportunity to apply for parole, with the help of a kind lawyer he was able to navigate the considerable bureaucratic obstacles and, after two-thirds of his life in prison, was released at the age of forty-one.

“No matter where you go in life, you bring yourself with you,” he wrote recently from Los Angeles, where he studied film production and found work. “If you have transformed yourself, you can face life in an open-hearted and courageous way.”

Gratitude

In the making of this book I’m grateful for the help of Geshe Thubten Sherab, Ven. Roger Kunsang, Ven. Holly Ansett, Ven. Jamyang Wangmo, Ven. Steve Carlier, Ven. Ailsa Cameron, Peter Iseli, Charmaine Hughes, Matt Bunkowski, Alessia Bulgari, John Castelloe, Nicole Mayo, Joona Repo, Tom Truty, Julie Cattlin, Gopa & Ted2 and Nick Ribush and his team, including Sandy Smith, at Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

– Robina Courtin