The sutra Do-de phal-po che,9 which contains teachings on bodhicitta, says, “The holy, altruistic mind of enlightenment, that purest of attitudes, is a treasury of merits.”

The Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life says, “How can one measure the merits one collects by generating the precious thought that is the cause of all happiness of all transmigratory beings and the medicine that cures the suffering of all sentient beings?”10

From where does every single happiness, both temporary and ultimate, of every single sentient being come? From bodhicitta. What is the one medicine for every suffering that sentient beings experience? That, too, is bodhicitta. Therefore, there’s no limit to the benefits of bodhicitta; there’s no way to realize how much merit you can collect with it. You can’t say it’s this much; it’s immeasurable. The merits you can collect with bodhicitta are numberless. That is the straight translation—“How can the merits collected by generating the precious thought that is the cause of the happiness of all transmigratory beings and the medicine for the suffering of all sentient beings be measured?”

With the mind of bodhicitta, each breath in and each breath out become a cause for the happiness of all sentient beings. With this purest of attitudes, bodhicitta, every breath you take benefits each sentient being and with each breath, with every action, you create skies of merit.

Therefore, if you want to accumulate the conditions necessary for attaining realizations on the path to enlightenment, you should put all your effort into developing your own precious mind of bodhicitta.

When you think of fulfilling your wishes, it’s not suffering you want. Normally, you don’t wish for suffering. What you wish for is happiness. Of course, the happiness that most of us wish for is actually suffering; what we usually think of as happiness is not pure happiness. However, as far as what we wish for is concerned, from the side of the wish, what we are looking for is happiness, not suffering.

That said, every single happiness—from that of full enlightenment, through liberation from samsara and the happiness of future lives, down to even the happiness of this life—depends on merit, good karma. Without good karma, nothing works. Without good karma, the cause of happiness, you can’t enjoy even the slightest happiness. Without merit, there’s no comfort; everything depends on merit. Realizations of the path, temporary happiness, even the work of this life, such as success in business—every single thing depends on merit. So, what’s the best way to collect extensive merit? It’s by practicing bodhicitta, meditating on bodhicitta.

Also, the merit you collect with bodhicitta is inexhaustible, unceasing. It doesn’t stop until you reach enlightenment, and even after you reach enlightenment it continues. You continuously experience the result; your mind remains in the state of peerless happiness. Not only that. As a result of the merits you collect with bodhicitta, you liberate numberless other sentient beings and bring them to full enlightenment. Without discriminating, you bring sentient beings equaling the sky, every single one, to the full enlightenment of buddhahood.

The teachings say that merits collected without bodhicitta are like a “water tree.” I think that means a banana tree—the fruit comes, you use it once and the tree no longer bears fruit. In other words, if merit is created without bodhicitta, you experience the result once and it’s finished. Merit collected with bodhicitta is completely different—you enjoy it all the time, lifetime after lifetime, and even after you achieve enlightenment, you keep enjoying it. Such merit is inexhaustible.

That’s why you should put all your daily life’s effort, everything you do, into developing bodhicitta. Whether you are happy or unhappy, whether you encounter problems or are problem-free, whatever your circumstances, favorable or unfavorable, whatever conditions you find yourself in, you must put every single effort into this, into living your life with the attitude of bodhicitta.

Now, when you do the Vajrasattva sadhana or other practices, even though they begin with bodhicitta motivation, when you come to the mantra recitation, again, just before you begin to recite the mantra, dedicate very precisely by thinking, “Each mantra I recite is for every hell being, each mantra is for every hungry ghost, each mantra is for every animal, each mantra is for every human, each mantra is for every sura, asura and intermediate state being.”

Even though you begin the practice with bodhicitta motivation, make sure that when you come to the actual recitation of the mantra it is directed more to the benefit of others than yourself. Make sure that instead of feeling in your heart that it is “I, me” for whom you are reciting the mantra, you feel that you are doing it for others. Make sure very precisely that each mantra you recite is for others, not yourself. Instead of filling your heart with “I,” fill your heart with others. Begin your mantra recitation like that; during the session, recite the mantra with as much bodhicitta as you can generate; and every now and then, check your motivation to make sure that your attitude is that of more concern for others than yourself. If it’s not, fix it.

If you want to be a lucky person, if you want good luck in your life, bodhicitta is the best way to create the good luck you desire. If you want to be lucky, put all your effort into practicing bodhicitta all the time. If you are a good hearted person you are truly lucky because gradually all your wishes get fulfilled—your wishes for your own welfare and your wishes for the welfare of others. You can stop all your defilements, your mental stains and errors, and accomplish all realizations, enabling you to liberate others from suffering and do perfect work for other sentient beings. Your good heart allows you to accomplish your own aims and those of others. That’s the definition of a really lucky person—one who has compassion for others, loving kindness, bodhicitta.

It also says in the Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, “Since merely thinking of benefiting others transcends making offerings to all the buddhas, what need is there to say how extraordinary it is to actually attempt to bring happiness to every single sentient being without exception?”11

Here Shantideva is saying that even thinking of benefiting others is much higher, more special, much greater and more extraordinary than making offerings to all the buddhas. Therefore, if you go beyond this extremely beneficial thought and actually try to bring happiness to all sentient beings without exception, actually work for their happiness, what need is there to say how extraordinarily beneficial this is, how far it surpasses making offerings to all buddhas?

Also, in his commentary to Maitreya Buddha’s teachings, Do-de-gyän [Mahayanasutralamkara], Arya Asanga says that benefiting one sentient being is more meaningful than making offerings to buddhas and bodhisattvas equaling in number the atoms of the world. How can it be that benefiting one sentient being is more meaningful than making offerings to not just one buddha but to buddhas equaling in number the atoms of the world?

This is incredible advice, similar to that given by Shantideva when he was talking about the benefits of bodhicitta, how extraordinary it is merely to think of benefiting others. For example, when we generate bodhicitta motivation, the thought of achieving enlightenment for sentient beings, the thought of benefiting sentient beings, merely this thought, just this wish, is greater than making offerings to all the buddhas.

Helping others is an offering to the buddhas

I mentioned before that when we help sentient beings we can also think of it as an offering to the buddhas. This is a very useful way to think.

There are many ways in which we can help sentient beings. I’m not just talking about our pet dogs and cats—and whether we keep them for their happiness or ours is also a question—but also insects. Actually, perhaps we should also keep insects as pets—mosquitoes, spiders... especially the ones we don’t like! Anyway, whatever sentient being we benefit—domestic animals, insects, hell beings, pretas, people—and whichever way we help them—for example, giving a Dharma talk to help somebody with depression or some other mental problem, medicine for illness or food or money to a beggar—sincerely trying to help either physically or mentally, we can always combine two things: making charity to that sentient being and an offering to all the buddhas.

If, for example, you give food or money to a beggar, you’re giving immediate help to that sentient being but at the same time it becomes the best kind of offering to the buddhas and bodhisattvas of the ten directions. Why? Because what the buddhas and bodhisattvas cherish all the time is sentient beings; nobody else. They are constantly working for sentient beings, cherishing only sentient beings. Therefore, when you help sentient beings you are helping the numberless buddhas and bodhisattvas. That’s the reality.

Even if you don’t think that your helping a sentient being is an offering to the buddhas and bodhisattvas, in fact it becomes the best kind of offering you can make, the most pleasing offering possible. As I also mentioned before, even though you don’t directly help the parents, when you help their children you make the parents happy, because what they cherish most in their lives, what they hold most dear in their hearts, is their children.

Similarly, if you harm a child you harm its parents, and in the same way, therefore, if you harm sentient beings you harm the buddhas and bodhisattvas; it displeases them greatly.

A child is like its parents’ life, or heart, and the buddhas and bodhisattvas cherish sentient beings in the same way. Therefore, if you do good things for sentient beings, if you benefit them, offer service to them, you are not only offering service to all the buddhas and bodhisattvas but the very best kind of service.

Thinking like this helps you practice tolerance, or patience. It helps you to not get angry at other sentient beings, to not arouse ill-will, to avoid hurting or harming them. It is very helpful. Inflicting pain upon a sentient being is like inflicting pain upon the buddhas and bodhisattvas. That’s not to say they experience pain in the same way that we suffering sentient beings do but it is certainly displeasing.

Therefore, when you offer service to a child or an old person, when you give things to others, for example, when you make charity to a beggar or even throw a party for others and offer them food and drink, remember that you are also making an offering to the buddhas and bodhisattvas. If you are aware of this, if when you give to the sentient being you also intentionally think you are making an offering to the buddhas and bodhisattvas, you combine two things. The sentient beings derive benefit from whatever you have given them and you collect merit by making an offering to the buddhas and bodhisattvas with your intentional thought.

If, at such times, you consciously think, “By helping this sentient being I am also making an offering to the buddhas and bodhisattvas,” if you remember that what you are doing with this sentient being also affects the buddhas and bodhisattvas, that doing something good pleases them, two things get done and you collect much more merit than you would have by simply making an offering, thinking of only the Buddha.

When you make charity, whether it’s an offering to monks, monasteries or refugees, homeless people or the sick, at that time remember that you are also making offerings to the buddhas and bodhisattvas; you are giving to sentient beings but offering to the buddhas and bodhisattvas. In this way you collect far more merit, an unbelievable amount.

The sutra Do-de phal-po che says, “The holy, purest thought of enlightenment is a treasury of merit (or fortune); from this come the buddhas of the three times.”

This means that numberless past, numberless present and numberless future buddhas have all come from bodhicitta, that holy, most pure thought of enlightenment. The text goes on, “From this [bodhicitta] comes the happiness of all the world’s transmigrators.”

The Tibetan phrase here is di-lä jig-ten dro-wa kun-gyi de-wa jung. Di-lä means “from this.” The next term, jig-ten, requires a little more explanation.

The meaning of “jig-ten”

The sense is “change,” but to make it clearer we should say “changeable aggregates.” We also have the term jig in one of the six root delusions, the one called five wrong views, ta-wa nga-ta ta-min nga. One of those is jig-tsog-la ta-wa, the view of the changeable aggregates. Here, jig is the same, meaning change. Ta-wa itself simply means view, but the implication here is wrong view, so together it becomes something like changeable wrong view. Jig-tsog-wa means changeable collection. What is that changeable collection? It is the five aggregates.

How does ignorance, the root of samsara, arise? How does that ignorance, which is the wrong view of the jig-tsog-la happen?

First, we have mig-kyen, the objective condition. The mind looks at the aggregates, which are impermanent and therefore changeable in nature, and labels them “I.” The thought thinks of the transitory aggregates and makes up the label “I,” the merely imputed I. But this I, which is merely imputed by that thought, doesn’t appear back to the mind as merely imputed. At that moment, you are not aware that the I is merely imputed by the mind.

Right after the I has been merely imputed by the mind, the negative imprints left on the consciousness by past ignorance, the concept of inherent existence, immediately project that the merely imputed I is inherently existent. Right after your mind merely imputes the I, just like imprints left on a film in a camera, the imprints left on the mental continuum by past ignorance—not just any ignorance, but the ignorance of inherent existence—immediately project the hallucination of inherent existence onto that merely imputed I . Buddhas cannot see this inherent existence; bodhisattvas who realize emptiness can’t see it; and when you analyze, even you can’t find it—because it doesn’t exist. What those buddhas and bodhisattvas see is a non-inherently existent I. That’s what they see.

However, with us, as soon as our thought merely labels I, in the very next moment, that merely imputed I appears back to the same continuity of thought as not merely labeled by mind, as existing from its own side. The very next moment of mind apprehends, “Oh, that’s true, that’s a real I there.” So, that real I appearing as true, seeing that real I appearing from there as true, is the wrong view, ta-wa.

Now you can understand the meaning of jig-tsog-la ta-wa a little better. Jig-tsog means changeable collection, in other words, the aggregates; ta-wa means view. When the next thought moment of the same continuity of the thought that merely imputed the I believes, or apprehends, that what is appearing to it is true, is something real from its own side, then at that time the jig-tsog-la ta-wa, the wrong view, happened. This wrong view is established on the aggregates, which are changeable by nature—like a table-cloth covering a table.

You can see the evolution, but since the wrong view is of the I, why does the term contain the aggregates, jig-tsog—the changeable collection (tsog means collection), the changeable aggregates? Why are they mentioned here, what’s the connection?

Well, by understanding the evolution of the wrong view, you can see why. By thinking of the aggregates, your mind labels I. First you think of the base and then you apply the label. The cause, or reason, for the mind applying a label has to come before the label; the reason, or cause, of the label has to come before the label. They don’t come together; the cause comes first. So, why is the particular label I chosen? Because first the base is identified, then the appropriate label applied

It’s the same with any phenomenon. By looking at the base, thinking of the base, seeing the base, hearing, touching, smelling or tasting the base, the mind that experiences the base and then creates the label, this or that. Depending on the base, the thought makes up the label and that’s how all phenomena come into existence, happen.

Abbreviating jig-tsog-la ta-wa, the view of the changeable aggregates, we say jig-ta. Jig means change and ta means view, but although literally it comes to changeable, or transitory, view, that’s not what it means. It is not the view that is changeable or transitory; the view is of the I. Change refers to the aggregates; the view is to do with the I.

Why am I describing ignorance here? Why, along with the wrong view, are the aggregates brought up? If you think of the evolution, you can understand. But now I should finish discussing the quotation from the sutra.

“From this comes the happiness of all the world’s transmigrators”—the term here is jig-ten dro-wa, so perhaps it should be translated as “transmigratory beings dependent on change,” since jig-ten means dependent on change.

It means that the I , the being, exists by depending on the aggregates. That’s what the “change” refers to. It means aggregates, which are transitory in nature, jig-ten. It really depends on the context. Actually, jig-ten is a general term that means both the world and its inhabitants—not only the place but also the beings that live there. It depends on the context. Usually it means suffering beings, jig-ten; samsaric beings, jig-ten-lä de-pa and jig-ten-pa—“those beings who are beyond dependence on change” and “those beings who are dependent on change,” respectively. In this context, jig-ten-pa means samsaric beings, “those who are dependent on change,” and jig-ten-lä de-pa means “those who have gone beyond samsara and are not suffering beings dependent on the aggregates,” which are changeable in nature, suffering in nature, that is, samsara. So jig-ten-lä de-pa means those who are beyond jig-ten

Here, ten means dependent on something; those who are dependent on change, which means the aggregates, transitory in nature, but also suffering in nature—that means samsara. Thus, jig-ten-pa means beings that are dependent on change, which means the aggregates. The aggregates are changeable in nature, suffering—that’s samsara. The aggregates are samsara.

“From this, the happiness of all the transmigratory beings dependent on change”—jig-ten dro-wa, dependent on change. That describes the aggregates, samsara. Beings who are dependent on the aggregates, which are changeable and suffering in nature—that’s samsara, the continuity of which circles from one life to the next. Beings that are dependent on that are called samsaric beings, circlers.

The next line says, “From this, all good things, all goodness praised by the victorious ones comes” or “From this, one receives all the goodness praised by the victorious ones.” It can be translated either way.

From bodhicitta, there is no doubt that you can become a buddha, one who is the victor over, who has conquered, defeated, destroyed, not only the delusions but even the subtle negative imprints of delusion. So, “From this, there is no doubt that you can become the principal victorious one”—amongst holy beings, the principal one, buddha, the most perfect of beings.

The next line: “With this, the defilements of all the jig-ten will cease.” Here, the jig-ten can mean all worldly beings. You can say, “All the defilements of worldly beings will cease,” but to my mind—I don’t know how it sounds to others—worldly has the connotation of “not being free from worldly concern, attachment clinging to this life.” Such beings are worldly beings, those who have not renounced attachment to this life. To me, “worldly being” has more this meaning than “samsaric being,” although here, worldly means samsaric. The Tibetan is di-ni jig-ten kun-gyi drib-pa se-par-gyur—“With this [bodhicitta], the defilements of all the jig-ten will cease” is the word-for-word translation—the meaning is the defilements of all samsaric beings or, you can say, the defilements of all the beings dependent on change, which means the aggregates, as we discussed above. All these defilements will cease.

On the other hand, I’m not completely sure what jig-ten refers to because even arya beings, like arhats, higher bodhisattvas and buddhas as well, exist by depending on aggregates. Even those who are free from samsara but still have subtle defilements—like arhats and higher bodhisattvas—exist in dependence upon aggregates. Not aggregates that are suffering in nature but those that are changeable in nature. Those who are free from samsara, arhats, don’t experience suffering, but they do depend upon changeable aggregates, jig-ten. So I’m not sure how widely the term jig-ten extends. Usually it means just samsaric beings but perhaps it can also cover those who still have subtle defilements—arhats and higher bodhisattvas.

The benefits of your own bodhicitta

While this quotation from Do-de phal-po che explains the incredible benefits of bodhicitta in general, you can also use it to think of the extensive benefits that come from your own bodhicitta. Thus, your own holy mind of bodhicitta is the treasury of all merit. Of course, you can’t relate the buddhas of the three times to your own bodhicitta, but they all do come from bodhicitta in general. Like numberless past, present and future buddhas arose from Guru Shakyamuni Buddha’s bodhicitta—not all, but numberless—you can relate to it like that. The happiness of numberless transmigrators dependent on change comes from your bodhicitta.

The happiness of all migratory beings comes from bodhicitta in general, but with your bodhicitta, you can still bring much happiness—the happiness of this life, future lives, liberation and enlightenment—to numberless sentient beings. Your bodhicitta can cause numberless hell beings, numberless hungry ghosts, numberless animals, numberless humans, numberless suras, numberless asuras and numberless intermediate state beings to experience all happiness up to enlightenment. All that comes from your bodhicitta, is caused by your bodhicitta.

You can even think very specifically. For example, your, one person’s, bodhicitta causes numberless ants to experience all temporary and ultimate happiness up to enlightenment. Think how many ants you can find at just one spot, how many thousands there are in a nest under a rock. There are so many more in a field or on a mountain. There’s no question how many more there are in one country. Like that, if you expand from one spot and think how many ants there are in this world, this universe, numberless universes, you can realize how many there are and how your bodhicitta brings them all happiness up to enlightenment.

Think how your, one person’s, bodhicitta brings all happiness to numberless other insects, numberless fish in the water, numberless shellfish on the rocks, on the piles supporting piers, in this world, in this universe, in numberless universes. If you think by elaborating in this way—the numbers of shellfish, for instance, are unbelievable, countless, and your bodhicitta, the bodhicitta of one person, you, can bring all happiness to all of them—it’s incredible.

Think of other sentient beings one by one. The worms in the ground—your bodhicitta brings all happiness to numberless worms. Caterpillars, those hairy ones that walk in such long, well-disciplined straight lines—uncountable, numberless caterpillars in just one spot, let alone this universe, numberless universes—your bodhicitta brings every happiness to them all. Or on the beach there are so many tiny crabs—you can see them when the tide goes out. They make all these little holes in the sand and when they come out looking for food the seagulls try to eat them. Think how many there must be in this universe, in numberless universes. The bodhicitta of you, one person, can bring them all happiness up to enlightenment. Think how unbelievable that is.

Even without thinking about the numberless hell beings, hungry ghosts, humans and so forth but merely thinking about the different kinds of animal and how each type is numberless, it is incredible that your, one person’s, bodhicitta can cause them to experience all happiness up to enlightenment and, as it says here, “With this [bodhicitta], the defilements of all those dependent on change [jig-ten, all the samsaric beings] will cease.” The bodhicitta of you, one person, can eradicate the defilements of each of the numberless animals, of whom even each type is numberless. Your bodhicitta can eradicate not only their suffering but also their two types of defilement. It’s unbelievable. There are so many different kinds of animal and even in this world, each one is numberless. When you think how many there must be in numberless universes and what one person’s realization of bodhicitta, the good heart, can do, how much it can benefit others, it’s really unbelievable.

Think how many flies there must be. Even on one cowpat there are thousands upon thousands of tiny flies keeping themselves busy, and that’s just on the ground. In the air there are so many more. You don’t notice them when the sun’s not shining but when it’s out you can see these huge clouds of flies in the air; uncountable numbers of tiny flies. From these few examples from the animal realm, just these few kinds of insect, you can understand how many suffering sentient beings there are.

Here I’m just talking about one spot on the ground but you should think of this world, then of numberless universes—how many unimaginable numbers of sentient being are suffering. Therefore if you, one person, have bodhicitta, it can stop all their gross and subtle defilements and put an end to all their suffering. That’s incredible.

The only solution to suffering

There are many animals, such as snakes, tigers, leopards and so forth, whose only food is other animals. They don’t eat plants; they don’t live on potatoes or carrots; they don’t grow vegetables. All they eat is other sentient beings. Snakes eat mice, frogs and so forth. There are many sentient beings whose only food is other sentient beings; who, due to karma, depend on killing others for their very survival. If you keep such animals as pets you have to feed them other sentient beings. For them, not eating others is suffering because they can’t survive in any other way and killing others is also suffering, since by harming others they create negative karma. Tigers in zoos, for example, have to be fed goats. Anyway, there are many sentient beings like this.

A while back in Singapore, where we frequently liberate many animals—frogs, fish and so forth—we bought five snakes from a restaurant in order to liberate them. When we opened the sack they were in they couldn’t crawl away immediately because they’d been sedated. It was as if they were drunk or on drugs! The thought came, if we release them, they’ll eat mice, but if we hadn’t freed them, they’d have become the restaurant’s evening special. Either way, it’s a problem. What we have to do is to free them from samsara; that’s the only solution—free them from delusion and karma. Until that happens, either mode of existence in samsara—killing others or not killing others—is a problem. The only solution is to free them from samsara.

The importance of the Dharma center

Therefore we ourselves should practice Dharma as much as possible and, if we can, spread Dharma and help other people understand it. If we can help those sentient beings who have precious human bodies understand the teachings and get them to practice Dharma as much as possible, we can effect that solution right away, right now. You can’t explain Dharma to snakes; you can’t teach them to meditate! You can’t start a meditation center for snakes, mice or tigers. You can’t establish a retreat center for mosquitoes, organize retreats for mosquitoes! There’s no way they can understand Dharma. Not even dogs or cats can understand it.

It’s important for you to practice Dharma as much as possible yourself, to actualize the path, and to help other people, those sentient beings who have human bodies, understand Dharma; to get others to practice Dharma. Actually, it’s unbelievably urgent, an emergency. The only sentient beings you can really help to understand Dharma, the path to liberation and enlightenment, are other human beings. In this way, they can avoid being reborn in the lower realms, as hell beings, hungry ghosts or animals. They don’t have to be reborn as mosquitoes. They can be saved from rebirth as snakes, tigers or other harmful animals. You can liberate people from rebirth in the lower realms, where you’re in danger if you try to survive and in danger if you don’t.

Who can you help right now? Human beings. The only way you can help animals is by taking them around holy objects or purifying them with blessed water. You can give them a little help like that but there’s no way that you can make them understand and practice Dharma. It’s only human beings you can help right now.

Therefore, you should make every effort to help human beings purify their past negative karma and protect their present karma by living in vows, by abstaining from negative karma. In that way they can liberate themselves from rebirth as, for example, those harmful animals we’ve been talking about. Not just that, but also free themselves from samsara and bring themselves to full enlightenment.

It’s essential that you practice Dharma yourself as much as you possibly can. And thus we see how very important the Dharma center is; how it plays a crucial role in saving, liberating, rescuing human beings from reincarnating back into the lower realms. The Dharma center is an emergency rescue operation, like when police go in with all that noise—sirens blaring, red and blue lights flashing, helicopters whirling—to rescue people in distress! Like that, the meditation center plays a very important role in the emergency rescue of people, human beings, using the seat belt and life jacket of the lamrim—meditation on refuge and karma immediately saves you from falling into the lower realms again. Then, on the basis of that, the center helps bring people to liberation from samsara and enlightenment. The meditation center, the Dharma organization, plays a very important role in this. This is the way to empty the lower realms, to ensure through Dharma that no more harmful sentient beings get born—doing sincere work with pure motivation solely for the benefit of others.

Numberless beings depend on you

Thus your bodhicitta is unbelievable. It’s unbelievable how much benefit you can bring to numberless sentient beings in each realm. Therefore, now, you can see how crucial it is—how the happiness of numberless sentient beings depends on you, how it’s in your hands. That means it depends on how much you practice bodhicitta, how much effort you exert trying to realize bodhicitta. It is crucial, most urgent, that you realize bodhicitta, train your mind in this.

Thus, the practice of bodhicitta becomes very important in your daily life. In all activities, under any circumstances—when you are happy, when you’re experiencing problems—at all times, never separate from bodhicitta. Never stop wishing that all sentient beings be happy. Never lose your determination for sentient beings equaling the extent of space to have all happiness and to be free from all suffering and, in this way, to lead them all to enlightenment.

If you live your life with this attitude constantly in mind, then, if you have taken the bodhisattva vow, you are able to protect it, by the way. Even though there are many different vows enumerated, if you live your life with this attitude, you take care of all those different vows. This attitude encompasses all those vows. If you never separate from bodhicitta in all your activities, each merit you create contains the three types of bodhisattva morality and the other paramitas as well.

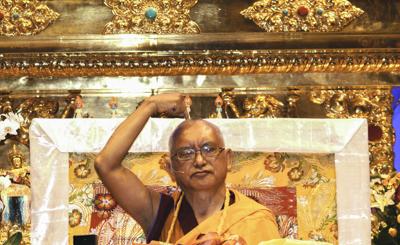

Lama Zopa Rinpoche gave this teaching 7 March 1999.

Notes

9. Buddhavatamsaka Sutra [Return to text]

10. Chapter 1, verse 26 [Return to text]

11. Chapter 1, verse 27 [Return to text]