This book brings together several motivations taught by Lama Zopa Rinpoche to be used first thing each morning to generate a bodhicitta motivation and, on the basis of that, train the mind in the bodhisattva attitude.

The motivations were first taught during the opening days of a series of experiential lamrim retreats called Light of the Path, highlighting at the very outset of the teachings the importance of motivation in our daily lives and activities. Several of the motivations were subsequently re-taught at various locations around the world and then collected together here.1

We can all understand the importance of motivation and attitude and how they affect the quality of our work and the result that can be achieved. Rinpoche particularly emphasizes the need for us to have a very clear direction and purpose in life. The real meaning of our lives is to bring both temporary and ultimate happiness to all sentient beings and to do this we need to achieve enlightenment. Enlightenment depends on first generating bodhicitta, and training our minds in these motivations and in the bodhisattva attitude helps us to do that.

In the introductory chapter of this book, Everything Depends on Your Attitude, Rinpoche explains why the mind plays such a crucial role in our lives and why having a good heart wishing to benefit all living beings is so essential. The following chapters contain two bodhicitta motivations that can be alternated each morning in our daily practice. The first and longest, Cutting the Concept of Permanence (chapter 3), is from sutra. The second and shorter, Give Up Stretching the Legs (chapter 4), is from tantra. A third motivation, Four Wrong Concepts (chapter 6), is specifically for taking the eight Mahayana precepts.

Each of these motivations is a guided lamrim meditation aimed at directing our minds into at least an effortful thought of bodhicitta. On the basis of that, we can then train in the bodhisattva attitude (chapter 5). What is it, this bodhisattva attitude? It is the spirit of total and uncompromising dedication to the welfare of others—almost inconceivable in the vastness and courageousness of its prayer and aspiration to be and to do whatever is necessary to benefit every single living being. It is, of course, the attitude exemplified by Rinpoche himself. It is also the attitude Rinpoche seeks to cultivate in his students, centers and those around him.

The bodhisattva attitude is beautifully expressed in a selection of verses composed by the great bodhisattva Shantideva in A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life.2 Rinpoche’s advice is to recite and reflect upon these verses each morning after generating a bodhicitta motivation and then use them throughout the day as a guide and inspiration for how to think and behave differently.

In some ways, these Bodhisattva Attitude verses are reminiscent of the famous prayer attributed to St. Francis,3 which directs our lives to selflessness and altruism. Similarly, this bodhisattva attitude opens our hearts to others and directs our minds towards enlightenment. Rinpoche explains that it is “totally against the ego and totally opposite to the self-cherishing thought.” There is only the wish to be used by others for their happiness.

The result of this way of practicing bodhicitta is deep happiness, peace, joy and satisfaction. How can this be so? Well, all of us seek happiness, yet we mostly fail to grasp the simple fact that happiness comes from cherishing others rather than perpetuating an ignorant and self-centered over-concern with ourselves.

Rinpoche puts it quite simply:

In the West, millions of people suffer from depression, but if you dedicate your life in the morning to numberless sentient beings, you will have unbelievable joy and happiness the whole day. Cherishing the I opens the door to all suffering, while cherishing others opens the door to all happiness. When you live your life every day for others, the door to depression, relationship problems and all such things is closed and instead there is incredible joy and excitement.

With the bodhisattva attitude you become wish-fulfilling for others. All sentient beings have been wish-fulfilling and kind to you since beginningless rebirths and now you become wish-fulfilling for them. From this, all your wishes for happiness will be fulfilled, even your wish to achieve liberation and enlightenment and to benefit others by causing them to have happiness in this and future lives, liberation and enlightenment. You will become the cause of all this for others. This is how to overcome all problems.

Clearly, the bodhisattva attitude is a total and radical change from our habitual way of following the selfish mind and negative emotional thoughts and cultivating it requires determined and sustained effort. The goal of this book is to inspire and provide materials for anyone who wishes to do so.

THE IMPORTANCE OF GENERATING A BODHICITTA MOTIVATION

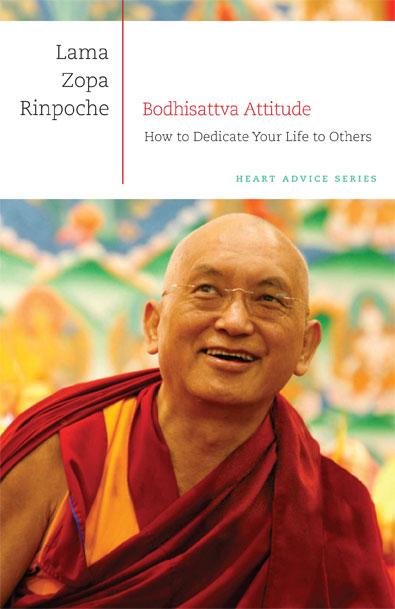

Anyone who has ever met Lama Zopa Rinpoche will know that he embodies every quality of love and compassion. His joyful laughter, kindness and generosity are legendary; it is quite obvious that everything he does is for others. His own life is a powerful display of bodhicitta in action.4 Not surprisingly then, in all of his teachings and practices Rinpoche emphasizes bodhicitta—from generating an extensive bodhicitta motivation at the beginning to making extensive bodhicitta dedications at the end.

Why is motivation so important? To understand this, we need to first be aware of how happiness and suffering come from our own minds. This is introduced in the opening talk, Everything Depends on Your Attitude, using a quotation from Lama Tsongkhapa’s Mind Training Poem:

White and black actions depend on good and bad thoughts:

If you have good thoughts, even the paths and grounds are good;

If you have bad thoughts, even the paths and grounds

are bad. Everything depends on your attitude.

In Buddhism it is the mind and particularly the motivation that is the key factor in determining whether our actions become virtue and a cause of happiness or not. Rinpoche uses Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche’s example of four people reciting the Twenty-One Praises to Tara prayer to illustrate this:5

The first person recites the Tara prayer with a motivation to achieve enlightenment for sentient beings and that person’s prayer becomes the cause to achieve enlightenment and a cause of happiness for sentient beings.

The second person recites the prayer not to achieve enlightenment for sentient beings but only to achieve their own liberation from samsara, so that person’s prayer does not become the cause to achieve enlightenment, but only to achieve liberation.

The third person recites the prayer not with a motivation to achieve enlightenment or liberation but just to achieve the happiness of future lives, samsaric happiness. That person’s action does not become a cause to achieve enlightenment or liberation from samsara, but only for the happiness of future lives.

Up to now, all three people’s action of reciting the Tara Praises has become Dharma. But the fourth recites the Tara prayer with a motivation only to achieve happiness for this life and this person’s prayer does not become Dharma. It does not become holy Dharma but only worldly dharma. This is what we have to understand. That action is non-virtuous because the motivation is only for the happiness of this life and therefore the result will be only suffering.

There are four levels of happiness described here and in each case it is the motivation of the person reciting the prayer that determines which level is achieved. Normally, we might think that the action of reciting a prayer is enough to create virtue, but this is not so—it is our attitude that makes all the difference.

Rinpoche comments on this story by warning us:

There is a similar story about two people who did Yamantaka retreat and one was reborn as a preta because his motivation was not Dharma.

There is a danger for this to happen to us. That is why it is extremely important to examine the motivation at the beginning of any action, and if it is not Dharma to make it Dharma. This is how to practice. When your motivation is Dharma, your actions become Dharma and the result is happiness. Otherwise you cheat your whole life because you believe you are practicing Dharma but you are not.

Therefore, if we want happiness, we have to pay very close attention to our minds and our intention. The whole point of setting a correct motivation from the very beginning of the day when we wake up is to make sure that all of our actions from morning to night do actually become virtue and a cause of happiness and none are wasted.

The best motivation is bodhicitta. Why? Because bodhicitta is the direct cause of enlightenment and the gateway to the Mahayana path. Training our minds in bodhicitta collects the inconceivable merit from which all other happiness comes and easily purifies unimaginable negative karmas.6 In Cutting the Concept of Permanence, Rinpoche describes bodhicitta as the “very essence of Dharma and the best way to make this life meaningful.”

Therefore, if we let our actions be guided by bodhicitta they will all become Dharma, and the happiness of this and future lives will come by the way without even seeking it. On the other hand, if our motivation is simply the happiness of this life, there is no guarantee we will succeed. Of course, most people are simply not aware that there is any happiness beyond this life and therefore their whole lives are spent seeking only that. Since they have no understanding of the correct cause of happiness, it is hard to say if they will ever find it.7

Knowing how to practice Dharma

There are two types of motivation, the motivation before the action—the “motivation of the cause”—and the motivation while engaging in the action—the “motivation of the time.” In a teaching given at Tushita Meditation Centre, Rinpoche recalls that the first question he ever asked Kyabje Chöden Rinpoche was, “For an action to become virtue, which is more important—the motivation of the time or the motivation of the cause?” To which Chöden Rinpoche replied, “The motivation of the cause.”8

The example of the four people reciting Tara prayers shows us that it is the motivation for doing the action that determines whether it becomes virtue, not the action itself. Bodhisattvas, for example, can engage in actions that appear non-virtuous, yet they are transformed into virtue through the force of their pure bodhicitta motivation, just as a peacock can transform poisonous plants into nourishing food. Rinpoche often cites the story of the Bodhisattva Sea Captain,9 a previous life of Guru Shakyamuni Buddha, who out of great compassion killed a trader who was planning to take the lives of five hundred merchants on board his ship.The captain could see with his immaculate clairvoyance the trader’s evil intention and, unable to bear the suffering it would cause everyone involved, he took upon himself the negative karma and consequences of killing one person in order to save all the others. However, because his motivation was one of great compassion, the action became positive instead of negative.

If we can make both the motivation before the action and the motivation during the action bodhicitta by generating a bodhicitta motivation in the morning and maintaining it throughout the day, all our actions will become a cause of enlightenment and bring the greatest benefit and happiness to ourselves and others. That means not only our “virtuous” actions of studying Dharma, meditating, reciting mantras and so forth, but even what are normally regarded as the “ordinary” actions of eating, walking, sitting, sleeping and working. This is extremely important and one definition of what is meant by “knowing how to practice Dharma.10

One very powerful technique to keep our minds focused on bodhicitta is to use a set of bodhicitta mindfulness practices frequently taught by Rinpoche and included in the back of this book.11 At the end of each motivation we generate the strong intention that all our actions become the cause of enlightenment and then use these mindfulness practices to keep that focus. Throughout his teachings, Rinpoche explains many ways to integrate bodhicitta into every activity of our lives. We have to use whatever method helps—our goal is not only to start the day with bodhicitta but also to live our lives with bodhicitta all the time. Rinpoche advises,12

Even though you have generated a motivation of bodhicitta right at the very beginning of an action, still when you engage in that action it is very important to feel in your heart that you are doing it for sentient beings. For whom are you doing the action—for you or for sentient beings? For sentient beings! The main concern should always be sentient beings. It is very, very good to try to feel this.

And,

My general advice is to try as much as you can to live your life with a bodhicitta motivation whatever it is you are doing, whether you are working, studying Dharma, doing meditation or praying. Then you become a most unbelievably fortunate person. You are able to achieve enlightenment quickly, to be liberated from samsara quickly, and to quickly liberate and enlighten other sentient beings.

Even if we are unable to maintain a bodhicitta motivation throughout the day, if we have at least generated bodhicitta first thing in the morning, it will make a huge difference to our lives. When bodhicitta is our “motivation for life,” as Rinpoche calls it, it transforms our actions into Dharma and the cause of enlightenment not only in this life but in future lives as well. Through the power of habituating ourselves to bodhicitta now, our future lives will again be drawn to bodhicitta and we will continue to practice in this way. If our present actions of eating, walking, sitting, sleeping, working and so forth are done with the thought to benefit all sentient beings, that will gradually bring us to the realization of bodhicitta, then up through the various pure and impure bodhisattva grounds to enlightenment. All these realizations start by training our minds in these bodhicitta motivations right now and then trying to live with bodhicitta all the time.

The most important thing is to make sure that our lives are not lived just to gain happiness and avoid suffering for one sentient being (oneself) but for all the numberless sentient beings. For many of us, this is a total and radical shift from habitual self-centeredness to limitless altruism that may at first be difficult to grasp. To give us a “picture” of what the mind of bodhicitta would be like, Rinpoche gives this example:13

There are numberless universes and in even one universe, one country, one area, one mountain or forest, there are numberless ants, an unbelievable number of ants. Can you imagine living your life for them? Dedicating your life to serve them, to free them from suffering and bring them happiness? Not only temporary happiness but also liberation from samsara and enlightenment. What could be better than that? There is no happier way to live life than with this bodhicitta attitude.

And, of course, when our motivation for life is bodhicitta, we are cherishing not just numberless ants but all sentient beings and living our lives only for them. Nobody is left out. In the Bodhisattva Attitude, Rinpoche says,

The bodhisattvas’ attitude is to always totally dedicate their lives day and night to be used by other sentient beings for their happiness. This is what they are seeking and wishing for all the time. You have to know that. If you feel like that, there is the opportunity to gradually become closer and closer to bodhicitta and have the realization. If you are able to change your mind into an attitude wishing to be used by others for their happiness, this is exactly what the bodhisattva attitude is.

Correcting mistakes in our practice

By understanding how everything depends on the mind, it becomes clear that we cannot judge whether an action is virtuous or not by its appearance. Therefore, we need to be constantly vigilant in our practice and not become complacent. Each of these motivations guides us through key points of the lamrim—which Rinpoche calls “the real meditation”—and they are full of warnings about what happens when Dharma is not practiced correctly.

In Cutting the Concept of Permanence, we are told that if we live our lives with the concept of permanence, we will never be able to give up attachment to the happiness of this life—which is the very beginning of Dharma—and without that, none of our actions will become holy Dharma, only worldly dharma. Our lives will then be full of endless problems and expense:

If the mind training in the meditation of impermanence is missing, look how much danger your life is in! There is no difference between a person who has met and studied Dharma and somebody who has not, between somebody who is a Buddhist and who is not, between somebody who has studied the philosophical or lamrim teachings extensively and who has not. It is like that.

You have to understand the point: sometimes there could be even more problems. Sometimes a person who has met Buddhism could have even more problems than one who is not a Buddhist, because although there is greater education and more learning, the basic practice has not been done, and since the basic practice is missing, the problems could be even bigger.

In Give Up Stretching the Legs, we are told of the danger of not putting effort into renunciation:

The world is full of examples showing how if you get attached to samsara and its pleasures thinking they are real happiness, you are totally cheated and suffer. In meditation, use as many of these examples as possible to get a clear understanding of the need to give up thinking samsara is good and engaging in it. This is very, very important.With this way of thinking, you can continuously practice Dharma. Otherwise, even if you try to practice, it doesn’t really become Dharma, a cause to achieve liberation; it just becomes another cause of samsara because the motivation is attachment.

Throughout the teachings, Rinpoche warns what happens if we don’t practice bodhicitta. For example, in the Bodhisattva Attitude:

I often hear people say,“Oh, these people are just using me!” Even sometimes at meetings in our centers I hear this.That is because they are not practicing bodhicitta. One time I wrote a letter to a center saying, “Bodhisattvas want to be used by sentient beings.” That is what the bodhisattvas’ attitude is.They actually accept it.The worldly mind thinks that being used by others is bad, the worst thing, but bodhisattvas are most happy to accept this.

In many ways, these motivations are not only to help us set up a bodhicitta motivation but also to examine, correct and heal any mistakes in our practice and lives that are causing problems. In Cutting the Concept of Permanence, Rinpoche says:

Like using a telescope to see something very far away or a microscope to see atoms or tiny sentient beings, similarly, here you use the Dharma to see your life and go beyond. By using Dharma wisdom you can see what is mistaken and what is correct; what is useless and what is useful; what is meaningless and what is meaningful; what is to be abandoned and what is to be practiced; what brings suffering and what brings happiness. It is all to do with the mind.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

The Verses

The first section of this book contains the verses on the Bodhisattva Attitude. They were composed by the great bodhisattva Shantideva in A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life14 and arranged into a prayer that appears at the end of the great lama Kachen Yeshe Gyaltsen’s chöd practice. Rinpoche translates the verses from this prayer, so there is a variation in one of the lines.15 Rinpoche also adds a concluding verse from the dedication chapter of Shantideva’s Guide.

The verses are to be read each morning on the basis of one of the bodhicitta motivations to remind us how we are going to dedicate our lives to others. They can also be recited and contemplated throughout the day. The point is to try to remember and live in their meaning.

There are elaborate and abbreviated ways of reciting the Bodhisattva Attitude. The longer version consists of reciting all the verses; the shorter way is to recite just the last three or two verses, which cover everything. It all depends on time. There is a commentary to the verses in chapter 5 and a meditation combining the verses and Rinpoche’s commentary in chapter 10.

The Teachings

The second section contains teachings on the motivations. In order to generate bodhicitta we need to train our minds in stages using a variety of methods and there is no better way to do this than by meditating on the lamrim. With these motivations we train our minds in the whole path to enlightenment and particularly in the three principal aspects of the path—renunciation, bodhicitta and the wisdom realizing emptiness—which are the very heart of all the Buddha’s teachings. Each of the motivations emphasizes a different aspect of these three principal aspects and each one has a different technique for bodhicitta, focusing mainly on the instructions for exchanging self for others.

Cutting the Concept of Permanence is the first and longest motivation. It begins with a meditation on impermanence and death and equalizing the eight worldly dharmas. Here the main emphasis is on counteracting our habitual ingrained belief that we are going to live for a long time, which is an obstacle to taking up serious Dharma practice. At the time of death our lives will appear to us like a flash of lightning that passed and finished so quickly, but up to that point ignorance blinds us with a false concept of permanence that makes us think we will live for a long time. If we do nothing to cut through this mistaken concept we will waste the precious opportunity we have to practice Dharma and secure the happiness of future lives up to enlightenment. How do we cut this concept? We need to understand that death can come at any time by training ourselves constantly in the thought that it can. On the basis of this, we then try to feel how precious this human life is and make the strong determination to engage in continual intensive Dharma practice—which means constantly integrating the three principal aspects of the path into our lives and living in vows.

In this motivation, having realized that we could die today, we decide that the most important practice for this and future lives is bodhicitta, and then train in the practice of exchanging self for others and taking and giving while reciting OM MANI PADME HUM.

The second motivation, Give Up Stretching the Legs, is shorter and based on a verse sung by the dakas and dakinis to awaken the tantric yogi from the sleep of clear light.Again, it begins with a reflection on impermanence and the need to give up attachment to this life and practice Dharma. However, the main emphasis in this motivation is on giving up attachment not just to this life but to all of samsara and its pleasures. This is extremely important because the stronger we can generate renunciation of our own suffering, the easier it will be when we turn our attention to others to generate aversion to their suffering as well and give rise to a strong bodhicitta intention.

We easily misunderstand what samsara is, thinking that it refers to all the pleasures of this life, which are real happiness. This makes it very difficult for us to want to achieve liberation. Therefore, Rinpoche begins by precisely defining samsara in a way that makes clear that it is only in the nature of suffering. There are three types of suffering—the suffering of pain, the suffering of change and pervasive compounding suffering. The suffering of pain is easy to understand—even animals can recognize this and want to be free from it. Most human beings, however, are totally unaware that their lives are afflicted by the other two sufferings and therefore have no thought of seeking liberation from them. Rinpoche focuses on the suffering of change, using a verse from the Guru Puja—“Samsara is extremely unbearable like a prison; please bless me to give up looking at it as a very beautiful, happy park”—to illustrate how our wrong belief that samsara and its pleasures are real happiness cheats us and keeps us continually circling in samsara, where every type of rebirth is pervaded by suffering.

In this motivation, we generate bodhicitta by contemplating a powerful Kadampa thought training advice:

I is the root of all negative karma; it is to be instantly thrown very far away.

Others are the originator of my enlightenment; they are to be immediately cherished.

“No matter what they do to you,” Rinpoche says, “sentient beings are always the originator of your enlightenment.”

In the next chapter there is an explanation of the Bodhisattva Attitude since these verses are to be recited following the previous two motivations. In all of these motivations, we are reminded how kind and precious other sentient beings are; the stronger we are able to feel this, the more natural it will be to cherish and want to serve them—which is what the bodhisattva attitude is all about. Our goal here is to generate the wish to totally sacrifice our lives for others—not just through prayer and reflection but also through our attitude and actions; not just to one or two people we like but to all; not just when we are in a good mood but also when we are depressed; not just now but forever. The stronger we are able to generate this bodhisattva attitude, the deeper will be our own sense of well being and joy and the quicker we will achieve enlightenment.16

The final motivation, Four Wrong Concepts, is for taking the eight Mahayana precepts. It has a very succinct teaching on emptiness as well as a reflection on the specific sufferings of each of the six realms that complement the previous motivations. The four wrong concepts are the four mistaken ways of viewing the world that have kept us trapped in samsara and suffering since beginningless time. The first two of these—viewing impermanent phenomena as permanent and suffering as happiness—have already been dealt with in Cutting the Concept of Permanence and Give Up Stretching the Legs. This chapter focuses on the main wrong concept and originator of the others, which is ignorance—the self-grasping of the person and self-grasping of the aggregates. In this motivation, Rinpoche guides us through a short, powerful meditation on emptiness and explains how to correctly identify the object to be refuted—the truly existent I.

This time when generating bodhicitta we reflect on sentient beings’ kindness in the following way:

It is amazing how kind sentient beings are. They are kinder even than Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, because Buddha, Dharma and Sangha came from the kindness of sentient beings.

By seeing that sentient beings are the most precious, kindest and dearest ones in our life, we are unbelievably happy to do anything we can to help them.

As for the lineage of these motivations, Rinpoche received Give Up Stretching the Legs from His Holiness Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche and Four Wrong Concepts from His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Cutting the Concept of Permanence and the Bodhisattva Attitude seem to originate from Rinpoche himself.

The introduction to the motivations, Everything Depends on Your Attitude, sets up several major themes that run through Rinpoche’s teachings, such as the importance of the mind and attitude, rejoicing, impermanence, bodhicitta, the urgent need to meditate on the lamrim and the importance of continual purification and accumulation of merit.

At the very heart of the introduction is Rinpoche’s story of his early life studying philosophy at Buxa refugee camp and how he met with the first ordained Westerners of the Tibetan tradition at a young age. It is hard not to draw a comparison between the appalling conditions and hardships endured by the Tibetan monk exiles in the refugee camp at Buxa, who persevered with their studies and subsequently became great teachers able to spread the light of Dharma throughout the world, and the first Western nun who died tragically in a landslide in Darjeeling due to not heeding the call to immediately leave her cottage because she was busy packing money into a briefcase.

In Four Wrong Concepts, Rinpoche remarks:

We have such unbelievable comfort and pleasure that we can’t imagine it. We are totally spoiled and pampered—yet we are still unable to practice Dharma!

Rinpoche’s own life-story calls upon us to reflect on the very root of the lamrim teachings, the qualities and kindness of the spiritual master. These heart advice teachings are a wake up call to immediately put all that we have learned into practice.

The Motivations

The third section comprises the actual motivations. These contain the key-points extracted from Rinpoche’s teachings. Each motivation is set up according to Rinpoche’s advice and keeps closely to his words. Most have a long and a short version. Readers can use these to familiarize themselves with the key points and integrate them into their lives.

The Appendices

Finally, the appendices contain material to support the motivations and the bodhisattva attitude.

There is a set of Morning Mantras (appendix 3) to be recited before or after the motivations to increase the effect of all our actions and the benefit they bring others and ourselves. I have also included a concise version of Rinpoche’s Bodhicitta Mindfulness instructions (appendix 4). This is a collection of slogans and yogas compiled by Rinpoche to help us maintain mindfulness on bodhicitta with each action that we do—walking, sitting, washing, sleeping, eating and so forth.The mindfulness practices are a very important tool for keeping our mind focused on the bodhisattva attitude. Both of the teachings in these two appendices were given at the same time as the bodhicitta motivations and the way of integrating these teachings is explained in How to Start the Day with Bodhicitta (appendix 1).

There is also a meditation on the stages of the path to enlightenment (appendix 2), Rinpoche’s adaptation of the Prayer of St. Francis (appendix 5) and some useful reflections on the shortcomings of the self-cherishing thought, the advantages of cherishing others (appendix 6) and the great need for compassion (appendix 7).

Most of the transcribing in this book is my own, except in cases where the original audio recordings were missing. The main teachings used for each chapter are listed in the footnotes.

The principal teachings referred to in this book are: Light of the Path Retreat, September 2009 (Archive number 1792) and 2010 (1838), Black Mountain, North Carolina, USA; Most Secret Hayagriva Retreat, March 2010, Tushita Meditation Centre, Dharamsala, India (1801); and two talks on motivation given at Shedrup Ling Center, October 2010, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (1844). Additional material and support was drawn from the 100 Million Mani Retreat, May 2009, Institut Vajra Yogini, Lavaur, France (1783); Guru Puja Commentary, February 2010, Jakarta, Indonesia (1796); Lama Tsongkhapa Guru Yoga Commentary, February 2010 (1795) and 2011 (1850), Amitabha Buddhist Centre, Singapore; Refuge and the Twelve Links, June 2010, Hong Kong (1817 & 1820); Milarepa Retreat, September 2010, Milarepa Center, Vermont, USA (1840); Sutra of Golden Light Transmission, December/January 2010/2011, Kopan, Nepal (1855); Three Principal Aspects of the Path, February 2011, San Francisco, USA (1856); Sutra of Golden Light Transmission, March 2011, San Jose, USA (1859); Lama Zopa Rinpoche Australia Retreat, April 2011, Atisha Centre, Bendigo, Australia (1861).17

All translations are based on Rinpoche’s own words and excerpted from the teachings unless otherwise indicated. In every case they are meant to convey the essence of Rinpoche’s commentary rather than be a precise translation of the original Tibetan or Sanskrit.Throughout the text I have tried to preserve Rinpoche’s voice. Rinpoche’s comments on the translation of Tibetan terms have been put as footnotes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book began as a private project as I was inspired by the beauty of the Bodhisattva Attitude. In the first teachings I ever received from Rinpoche, he taught on this prayer to become like “the earth, water, fire and wind” for sentient beings.18 That was many years ago, when I had never seen or heard of such a thing before, and since Rinpoche so clearly embodied the prayer, it deeply moved me.

Therefore, from beginning to end, I have nobody to thank but Rinpoche. I pray that the collective effort to publish this book may in some way repay his kindness in giving these teachings, act as a cause for his perfect health and long life and support his enlightened activity.

Many people were kind to and supportive of me as I worked on these teachings and I am extremely grateful to them all. Particularly I would like to thank Rowena Meyer in Santa Fe and Dr. Chiu Nan Lai, Ven. Chosang and family for helping me in Crestone. Thank you to Lynne Ingram and Nick Jablons; to Ale Almada, Jim and Cherie Sutorus; and to Amy Cayton and Annie Moon. Also Fabienne Pradelle, Heidi Oehler and everyone at Vajrapani and Denice Macy and everyone at Land of Medicine Buddha; both of these centers provided a place for me to work on the book, as did my dear friend Mary-Beth Harhen. Sarah Shifferd was always very generous with her editorial help and for technical assistance I relied on the patience, wisdom and kindness of Ven. Stephen Carlier, Ven. René Feusi, Ven. Tenzin Dekyong and Charles Smith. Ven. Jangchub, Ven. Yangchen, Ven. Jampa Michele and Miranda Reyna-Metzler also read the manuscript and gave valuable suggestions. Thank you to Ven. Kunsang for recording the teachings and Ven. Joan Nicell for typing the initial simultaneous transcripts.

The students at Amitabha Buddhist Centre, Singapore, sponsored the first booklet of Bodhisattva Attitude19 for Chinese New Year 2011 and also funded this current book. I thank them all for their kindness, especially Tan Hup Cheng, Cecilia Tsong, Lim Cheng Cheng, Ng Swee Kim, Kennedy Koh and Shirley Ong, who took care of me during my visits to Singapore.

My deep thanks also to Dr. Nicholas Ribush, Wendy Cook, Jen Barlow and all at the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. “Dr. Nick”—as we know him—along with Ven. Robina Courtin and Ven. Ailsa Cameron, has worked so hard for years to preserve, edit and publish Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s teachings.

Thank you, Nick, for all your editorial work and patient support as well as your encouragement and vision to create the Heart Advice Series.

Sarah Thresher

Lama Tsongkhapa Day

Crestone, Colorado

December 2011

NOTES

1 See Technical Note for a full list of teachings used in the book and how to access the original audio, video and transcripts at the LYWA website or FPMT Online Learning Center. [Return to text]

2 See chapter 1. [Return to text]

3 See appendix 5 for Rinpoche’s adaptation of this prayer. [Return to text]

4 Ven. Roger Kunsang, Rinpoche’s long time assistant, has described Rinpoche as “bodhicitta in a human form.” [Return to text]

5Light of the Path, 14 September 2009. Pabongka Rinpoche cites this in Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, Part One, p. 141. [Return to text]

6 For more on the benefits of bodhicitta, see Liberation, Part Three, pp. 99–120. [Return to text]

7 See Light of the Path, 13 September 2010.There are four levels of happiness—the happiness of this life, future lives, liberation and enlightenment. The happiness of this life is not a goal in the path to enlightenment teachings and seeking it is not a Dharma action, but nonvirtue. However, it is explained that the happiness of this life comes naturally as a by-product of working for the other three levels of happiness. See The Door to Satisfaction, ch. 4. [Return to text]

8 Most Secret Hayagriva Retreat, 14 March 2010. Kyabje Chöden Rinpoche is an outstanding scholar, yogi and master of Sera Je Monastery and one of Rinpoche’s gurus. [Return to text]

9 For example, in Door to Satisfaction, pp. 45–46. [Return to text]

10 Rinpoche’s definition of “knowing how to practice Dharma” is either knowing all the different meditations involved with a practice such as Lama Chöpa Jor Chö in order to purify and collect merit as extensively as possible, making the practice most effective, or knowing how to make all our actions, spiritual and worldly, virtuous. (Sutra of Golden Light Transmission, 20 March 2011).[Return to text]

11 See appendix 4. Rinpoche collected and translated these bodhicitta mindfulness practices to be used in retreat and daily life. [Return to text]

12 8 February 2010, Lama Serlingpa Bodhicitta Study Group, Jambi, Sumatra. [Return to text]

13 16 February 2010, Amitabha Buddhist Centre, Singapore. [Return to text]

14 See note 21. [Return to text]

15 See note 80. [Return to text]

16 Rinpoche: “Whoever has stronger compassion for sentient beings and is able to sacrifice their life from the heart to others can achieve enlightenment quickest.” This is illustrated by the story of Maitreya and Shakyamuni Buddha. Maitreya generated bodhicitta first, but in a previous life, when they were both princes and saw a starving tigress, although both had compassion, Buddha’s compassionwas stronger and he was able to offer his body to the hungry tigress. Therefore Shakyamuni Buddha became enlightened before Maitreya. (Lama Zopa Rinpoche Australia Retreat, 14 April 2011). [Return to text]

17 To access the original teachings, go to LamaYeshe.com and search for the Archive number (the number in brackets, above) using the “Search the Archive Database” link on the home page. Some of these teachings—such as Light of the Path—are also available in audio, video and transcript form along with related study modules at the FPMT Online Learning Center, onlinelearning.fpmt.org [Return to text]

18Fifteenth Kopan Course, November 1982 (Archive number 95). [Return to text]

19 Copies of this may still be available from ABC and LYWA. [Return to text]