It was 1972 and I was traipsing along South-East Asia’s hippie trail having too much fun when, in Thailand, I stumbled into Buddhism. I was an Australian physician who for various reasons had taken a four-year break from medicine to travel the world looking for I’m not sure what, but it certainly wasn’t anything spiritual. Nevertheless, in Thailand I encountered some of the external manifestations of Buddhism, such as temples and monks begging daily for alms, so as a dutiful tourist, I decided to read up on the culture.

The book I happened to pick up was a Penguin paperback called, simply, Buddhism, written by an English high court justice named Christmas Humphries. This was by no means a profound tome and I wouldn’t even recommend it to anyone today, but some of the things I read stirred my heart in the strangest way and I knew I had to look into Buddhism more deeply. One thing that the author stressed was the importance of meditation, and I made a mental note to find out more about this later.

Traveling on through Laos, Burma and India, a couple of months later I found myself in Kathmandu, Nepal, where a Brazilian acquaintance from the trail told me about a one-month meditation course given by a couple of Tibetan lamas that was about to begin at nearby Kopan Monastery. I signed up. Thus began the rest of my life.

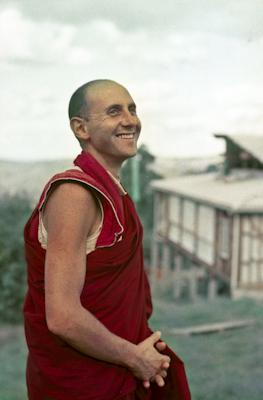

The main teacher was a young monk in his twenties, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, the incarnation of a famous yogi who had meditated for many years in the high Himalayas of Nepal, not far from Mount Everest and Tibet. His guru, Lama Yeshe, a great master who has played a major role in the transmission of Buddhism to the West, also taught. Here’s a bit of what I learned.

The main thing studied in Buddhism is the mind, but not the mind in general so much as one’s own mind. Actually, I found the learning process extremely scientific and not particularly at odds with my medical training. The teacher would lay out the principles of Buddhist philosophy and psychology and we would then think about them, subject them to critical analysis, and meditate on them, using these teachings as a mirror for our own mind. Day in and day out for thirty days we got up early, meditated, listened to teachings, meditated, discussed, listened to more teachings, meditated and went to bed. By the end, while still not accepting everything I’d heard, I knew I had to stay to find out more.

I found out that the mind and the body are interrelated but completely different in nature. The body is physical, made of atoms; it has shape and color. The mind is formless, clear light in nature, and has the ability to perceive objects; there’s no way it can come from the brain. The body starts at conception; the mind is beginningless. At conception, the consciousness, which comes from the previous life, enters the fertilized egg. Each individual’s previous lives are infinite in number and it is one’s own discrete stream of consciousness that passes through them all. Thus, our present mind is the result of everything we have ever been and done, and our future mind and lives depend upon what we do today. This is the same for all of us.

The good news is that all sentient beings have the potential to reach enlightenment, the highest possible state of mind, everlasting, blissful happiness, because we all have clear light nature of mind. Enlightenment is what the Buddha himself attained way back in India more than 2,500 years ago, what he shared with his disciples, and what has been taught by a succession of Indian, Tibetan and other masters in an unbroken lineage going back to the historical Buddha himself.

A sentient being is a being whose mind is ignorant; a buddha is a being who was once a sentient being but became enlightened by totally purifying his or her mind of ignorance and fully imbuing it with the qualities of compassion and wisdom. Buddhist meditation teaches us to cleanse our own minds of ignorance and the other delusions that spring from it, such as attachment, jealousy, pride and hatred - which obscure our mind’s clear light nature and are the actual cause of all the suffering we experience - and to develop desirable attributes such as love, compassion, tranquility, concentration and divine intelligence, which are the cause of all happiness.

Generally speaking, Buddhist meditation is of two types - analytical and concentrative. In analytical meditation, we use our powers of logical reasoning to examine the teachings to determine for ourselves whether or not they are true, to eradicate doubt, and to come to a clear and unshakable conclusion about the way in which things exist. In concentrative meditation we learn to focus our mind single-pointedly on a mental object until our mind can rest effortlessly on that object for hours or even days at a time. Although they are quite different in nature, these two types of meditation assist and support each other. The better we can analyze, the greater our conviction for practicing concentration and trying to overcome the obstacles to success; the better our concentration, the stronger our powers of logical deduction and the clearer the conclusions we reach.

So, what’s the point of all this? Why make all this effort? Well, we all want to be happy and none of us wants to suffer or experience any kind of problem, but obviously, our wishes alone are not enough to bring all this about. We rarely find the happiness we desire and when we do, it doesn’t last and usually isn’t as good as we’d hoped it would be. Furthermore, we’re constantly experiencing one problem after another - running into undesirable situations, not finding what we want or losing what we have, not to mention getting sick, aging and, at the end of it all, dying. To understand Buddhism’s explanation of why our lives are like this and what we can do to improve them, we need to understand the Buddhist world view.

As I mentioned before, there are two kinds of being with mind - sentient beings, whose minds are ignorant, and enlightened beings, from whose minds every last trace of ignorance has been eradicated. Sentient beings are also of two types, those in cyclic existence (Skt. samsara) and those free of it. Within cyclic existence, there are six realms, three lower - the animal, hungry ghost and hell realms - and three upper - the human, demigod and god realms. Most sentient beings have been in cyclic existence, dying in one realm and being reborn in another, since beginningless time. Beyond this wheel of life, there are two states of existence - individual liberation and the full enlightenment of buddhahood. The point of Tibetan Buddhist meditation, the ultimate point of all Buddhism, in fact, is for all sentient beings to attain enlightenment. But enlightenment can be attained only through individual effort; we have to do it for ourselves. God or Buddha cannot do it for us. The way to enlightenment is to follow the path that leads to it.

The first thing to understand is that it all begins with motivation. Whether an action becomes positive karma, the cause of happiness, or negative karma, the cause of suffering, depends on why it is done. All actions done with attachment to the happiness in this life alone, actions done simply for the comfort of this life, are negative. The karmic imprints such actions leave on the consciousness eventually ripen into an experience of suffering. Actions done with the motivation of experiencing happiness in a future life, actions done with detachment from this life, are positive. The imprints they leave ripen into happiness.

There are three kinds of positive action, three levels of positive motivation. The first is that seeking happiness in a future life within cyclic existence - rebirth in the upper realms or ordinary, temporary samsaric happiness of one kind or another. The second is seeking complete liberation from cyclic existence for oneself alone. The third is seeking enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings, understanding that in the final analysis, all happiness comes from other sentient beings and that it is one’s individual responsibility to lead them all to the highest happiness of enlightenment. Actions done with any of these three levels of motivation plant the seeds of harmonious results.

Tibetan Buddhist meditation always stresses the importance of the third, or highest, level of motivation, which is known by its Sanskrit name, bodhicitta. Everything we do should be motivated by the supreme altruism of wanting to see all sentient beings enlightened. If it is, we ourselves automatically also experience good results. This paradox - if you want to experience the greatest happiness, forget about yourself and devote yourself solely to the happiness of others - is what the His Holiness the Dalai Lama calls “wise selfishness.” Since we’re going to be selfish, we might as well be smart about it.

Thus, the benefit of our actions is not determined by the action itself but by our motivation for doing it. If, for example, we meditate for selfish reasons or for some mundane goal such as tranquility now, even though it might look as though we’re doing something spiritual, in fact, because of the worldly motivation behind it, that action will leave a negative imprint on our mind and is therefore the cause of suffering. Thus, Tibetan Buddhism teaches us to do everything with compassion, thinking about the suffering of others and wanting to alleviate it. In this way, too, even everyday actions such as sleeping, eating and working can be transformed into the cause of enlightenment.

Analytical meditation is usually practiced on teachings from the graduated path to enlightenment. This path structure is another feature of Tibetan Buddhism, wherein all the teachings of the Buddha have been arranged in a logical, step-wise order that makes them easy to understand and practice. When I saw the steps of the path laid out, like a mental road map to spiritual perfection, I thought, “Now I’ve witnessed a miracle.” To think that every step on the way to developing our minds to their fullest potential has been so clearly explained and that by generating these realizations in our minds we can become, essentially, one with God, was mind-blowing. I don’t have room to outline this path here, but I would encourage those who are interested in these teachings to look more deeply into them. You will discover how to make life meaningful and fulfill the purpose of having been born human this one precious time.

Concentrative meditation usually starts with learning to focus on the breath. This is an important technique, akin to stretching before physical exercise. The ideal, recommended meditation posture has seven features:

- Sit cross-legged on the floor, preferably in the full- or half-lotus position, with a cushion beneath your buttocks.

- Keep your back straight, with your vertebrae one above the other like a pile of coins.

- Keep your shoulders level and parallel with the floor.

- Hold your arms slightly rounded and away from your body, with your hands in your lap, palm upwards, right on top of the left, tips of the thumbs touching.

- Bend your neck slightly forward, with your chin tucked in a little.

- Close your eyes lightly or open them slightly, with your gaze down the line of your nose.

- Also close your lips and teeth lightly, with the tip of your tongue touching the roof of your mouth just behind your top teeth.

Once you are seated comfortably, generate bodhicitta meditation, thinking, “I am going meditate on my breath in order to reach enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings.” Then bring your attention to your breath, focusing your mind on the entrance of your nostrils, where you can feel the air entering and exiting your body. Breathe normally; the difference being that now you are paying full attention to your breath. Keep your mind on your breath but don’t think, “I’m breathing” or something like that. Just let go and let be. However, if it helps you focus, you can count the breaths, seeing how high you can go before you discover that you have lost concentration and your mind has gone off on something else. At that point, drop whatever distracted you like a hot potato and immediately come back to your breath. This is the way to begin practicing meditation.

This is all we have space for here, but if you are interested in looking into this subject further, please read How to Meditate, by Kathleen McDonald (Wisdom Publications, 1984, 2005). The best book detailing the path to enlightenment is Pabongka Rinpoche’s Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand (Wisdom, 1991, 2006). These two books are available from Wisdom Publications. Also recommended is Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s Teachings from the Vajrasattva Retreat (Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive, 2000).