THE SUPREME MIND

How incredible that we are here now, with this unbelievable opportunity! We not only have this human existence, but we also have what in Tibetan Buddhism is called a perfect human rebirth, a rebirth in which we enjoy the eight freedoms and the ten richnesses1 that make this the very best time to develop our mind along the path to enlightenment, the one path that will guarantee us not just complete freedom from all suffering but the ability to help all other beings to that same blissful state.

This perfect human rebirth we have now gives us such a unique position, but besides being extremely difficult to find it is also extremely fragile, because we can die at any time. In any other rebirth, in the lower realms or the god realms,2 we will be totally unable to create any virtue and so plant the seeds for future happiness. And even if we were to be reborn as a human being, it is very easy to see how few other humans share our good fortune in being free from poverty, illiteracy, oppression or any of the many other sufferings that plague our world. The most amazing thing of all is that we have met the teachings of the Buddha and we have the inclination to study and follow them. We need to see the uniqueness of this opportunity we now have and to make the most of it by following the Buddhadharma, the method that will definitely lead us from happiness to happiness.

All of the Buddha’s teachings are solely to lead us out of suffering and into the peerless happiness of liberation and full enlightenment. All 84,000 teachings are summarized in his teaching on the four noble truths, the first discourse he gave after he became enlightened under the bodhi tree in Bodhgaya, over 2,500 years ago. Everything we study about Buddhism comes into these four noble truths: the truth of suffering, the truth of the origin of suffering, the truth of the cessation of suffering and the truth of the path leading to the cessation of suffering. Furthermore, it can all be summed up in the Buddha’s wonderful quote:

Do not commit any nonvirtuous actions,

Perform only perfect virtuous actions,

Subdue your mind thoroughly—

This is the teaching of the Buddha.

With the first two noble truths the Buddha showed suffering in its entirety and the origin of that suffering. The third noble truth is the truth of cessation, where he showed that it is certainly possible to cease this seemingly never-ending round of contaminated birth after contaminated birth. The fourth noble truth is the truth of the path that leads to cessation. Every word the Buddha uttered is purely to lead to the cessation of suffering, so this fourth noble truth encompasses the entire Buddhist path. We refrain from harming others by not committing any nonvirtuous actions and we help them by performing only virtuous actions, and this is all done through subduing our deluded mind. This is what is called the Dharma. Whenever we follow his teachings by renouncing nonvirtue or by creating virtue, we are practicing the Dharma, whether we call it that or not, whether we consider ourselves Buddhist or not.

In Tibetan Buddhism these incredible teachings have been classified into a system that makes them easy to study and actualize, called the graduated path to enlightenment (Tib: lamrim). There are three main areas we need to develop: renunciation of samsara, bodhicitta, which is the altruistic intention to become enlightened in order to enlighten all sentient beings, and right view, the understanding of emptiness. In the lamrim, these three areas are set out in a progressive series of teachings, from the need for a spiritual guide at the very beginning to the most subtle minds that are needed for enlightenment at the very end. In the lamrim we will find everything we need to take us all the way to the ultimate state of enlightenment.

In fact, I can definitely say that the lamrim is the very quintessence of the Dharma. When the great Indian teacher Atisha went to Tibet from the Buddhist university of Nalanda in India in the eleventh century, he condensed everything the Buddha taught into this graduated path, with nothing missing. After that, the great Tibetan teachers such as Lama Tsongkhapa wrote commentaries on the lamrim, and to study these commentaries is to see just how the lamrim presents the whole picture.

Without studying the lamrim it is very difficult to appreciate how precious and rare our current situation is. Perhaps we try to meditate, perhaps we pray or read sutras, perhaps we call ourselves a Buddhist, but without a good background in the lamrim it is unlikely we will be able to grasp how crucial it is to practice Dharma and do nothing but practice Dharma. It’s the most important thing in life. And of all the aspects of the Dharma, the very heart is bodhicitta.

There are many things we can develop in order to progress on the path, such as equanimity, the wisdom of how things exist, an understanding of karma and so forth, but the greatest thing we can strive for is the peerless mind called bodhicitta. “Bodhicitta” is a Sanskrit word that just means the mind of enlightenment, with bodhi meaning “awakened” or “awakening” and citta meaning “mind.” This is the mind that strives for complete enlightenment in order to best be able to benefit all sentient beings. It is the mind that completely, spontaneously, continuously works for nothing other than the benefit of all living beings. A person who possesses such a priceless mind is called a bodhisattva.

From countless rebirths until now we have only ever done things for our own happiness, often at the expense of others. With bodhicitta, we put self-interest aside and work solely for others. The “happiness” our self-cherishing has sought for us has in fact been a fantasy, and, as we can see when we study subjects like the four noble truths, any mental state poisoned with attachment to sense pleasures—what we would normally consider worldly happiness—is actually suffering, in that there is an underlying dissatisfaction that will lead to future grosser suffering. On the other hand, when we put that selfish mind aside and start working for others, we effortlessly attain, as a byproduct, a real sense of happiness that will never let us down. Not only that, we are developing our mind toward its ultimate potential, the fully awakened mind of enlightenment. As I often say, real happiness begins when we start cherishing others.

This perfect human rebirth we have is incredibly rare. We need to be aware of how rare and fragile our situation is and determine to not waste even a second of this life we have. By seeing that attachment to the pleasure of this life is still in the nature of suffering, we need to renounce it all. Like honey on a razor blade, it may seem sweet and desirable, but if we try to grab at it we will only experience suffering. It is a matter of recognizing samsaric pleasure as suffering and firmly renouncing it.

Each of the three principal aspects of the path is vital. We can develop single-pointed concentration, we can renounce the whole of samsara, we can even realize the emptiness of all phenomena without developing bodhicitta, but we can’t become fully enlightened unless we have bodhicitta. Without bodhicitta we can’t enter the Mahayana, the Great Vehicle, that allows us to become free from not only the gross defilements but even the subtle obscurations to knowledge that block us from full enlightenment. Only with this can we free ourselves from even the most subtle suffering.

Releasing ourselves alone from suffering is not enough. There are infinite sentient beings having to endure incredible suffering. How can we just work for ourselves when they are helplessly drowning in the great ocean of samsaric suffering? They have benefited us, not just in this life but in all our previous lives. They have been our mothers, our fathers, our friends—we have had every possible relationship with every being—so we can’t turn our backs on them now. In order to repay them for the great kindness they have shown us we must guide them out of their suffering. We must help them find true happiness and especially the happiness of full enlightenment. But we can’t do that until we ourselves are enlightened. Therefore, the motivation we must start every day with, every action with, is this wonderful bodhicitta motivation, to attain enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings.

Bodhicitta is the fuel that propels our rocket to the goal of enlightenment as quickly as possible. We must not waste a moment because every moment we delay, not only are our kind mother sentient beings suffering, but we could also lose this most precious life at any time. Every causative phenomenon—anything that is a product of causes and conditions—is in the nature of impermanence, and our body is no exception. We all know we will die one day, but for most of us that day seems too far in the future to worry about. That is entirely wrong. We could die at any moment. Tens of thousands of people who woke in their bed this morning will not return to it this evening, dead for some reason or other, and very few of them had any notion of what awaited them during the day. Our next inhalation might not be followed by an exhalation. That is a fact. That is how fragile this life is, whether we deny it or not. Therefore, we must not waste a second of this precious life. And the very best use we can make of this life is to develop bodhicitta.

A bodhisattva becomes a buddha based on bodhicitta. Training the mind in bodhicitta is the best method to quickly and extensively purify the negative imprints on our mindstream that currently block us from attaining any of the realizations we need to develop toward buddhahood. Even if we knew all the scriptures by heart and even if we were experts at practicing the Highest Yoga Tantra meditations of both the generation and completion stages, none of this would be the cause of attaining enlightenment without bodhicitta.

There are many stories of meditators who spent their life meditating on tantra, generating themselves as a deity such as Yamantaka, but who, due to their unskillful tantric practice, were reborn as a hungry ghost in an aspect similar to their visualized deity. This happened because they focused only on the tantra and forgot the lamrim practices of renunciation, bodhicitta and emptiness.

To waste even one second of this perfect human rebirth is a loss far greater than losing diamonds equaling the number of atoms of this world. Even if we had wealth equaling that of all the human and god realms combined, that wealth would do nothing to assure our genuine happiness or the happiness of others. One brief moment of a mind of bodhicitta will do that, however, and hence it’s far more valuable than any worldly object. We need to consider our life in light of this, examining whether what we do every day brings us closer to enlightenment or whether we are just chasing after worldly goals such as career and possessions that consequently tie us further to the suffering of samsara. If we are still unable to separate from the self-cherishing attitude that places our own interests above those of others, we need to consider the terrible disadvantages of self-cherishing and the wonderful advantages of cherishing others and we need to see what an incredible loss such a self-centered life is.

When our mind is attached to worldly pleasures no matter what we do, it will be wasted. It will not be a Dharma action, a virtuous action that leads us from suffering and toward true happiness. It will only lead to more attachment, more aversion, more ignorance, more dissatisfaction, more suffering. Even though we try to do a spiritual action, such as meditating, saying prayers and so forth, it will still not be Dharma because it will be tainted by self-cherishing. No action can be a Dharma action and a worldly action at the same time, and unless it is a Dharma action it will surely lead us into further suffering.

No matter how privileged our life is, how many possessions and friends we have, how many enjoyments we are able to experience, no matter how pleasant our future life will be, this is all in the nature of suffering. It is still in bondage to suffering, and because we are locking ourselves more and more into self-cherishing it can only lead to terrible suffering in the future, probably to rebirth in one of the lower suffering realms as an animal, a hungry ghost or a hell being.

On the other hand, bodhicitta is the best method to attain our own wishes and the wishes of all other sentient beings, those infinite other sentient beings from whom we have received all our past, present and future happiness. They have been responsible for every happiness we have ever experienced, no matter how big or how small, and the best way to repay that kindness, the only real way, is to become enlightened ourselves and to then be perfectly equipped to guide them from suffering to perfect enlightenment. This is why we must train in the lamrim path and especially study bodhicitta.

Of the two aspects of the Buddhist path, wisdom and method, the wisdom side is understanding the nature of reality, which generally means understanding emptiness, and the method side is mainly to do with developing ways of attaining this most precious mind of bodhicitta. Love, compassion, equanimity, morality—whatever positive aspect of our mind we develop leads us to bodhicitta. These methods come from Guru Shakyamuni Buddha and were expounded by the unsurpassable teachers like Manjushri, Lama Tsongkhapa and Shantideva.

In A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, the great bodhisattva Shantideva says,

[1:7] Having checked for many eons what is most beneficial

To bring sublime happiness to infinite sentient beings,

Shakyamuni Buddha and all the buddhas have discovered,

It is to have a mind imbued with bodhicitta.

There are two profound methods for developing bodhicitta. The first is the seven points of cause and effect—seeing all beings as our mother, recalling their kindness, determining to repay their kindness, love, compassion, the special intention to take responsibility for their happiness, and bodhicitta itself—and the second is equalizing and exchanging the self with others. Only by practicing these Mahayana techniques can we not only overcome our own problems but also be able to perfectly work for the happiness of others. We see that all sentient beings are suffering in samsara and how unbearable that is, and from the great compassion that arises with this thought we generate the supreme mind of bodhicitta.

VERSES OF INSPIRATION FROM KHUNU LAMA RINPOCHE

The supremacy of bodhicitta is the message of the wonderful book written by Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen Rinpoche, called The Jewel Lamp: A Praise of Bodhicitta.3 It is quite similar to Shantideva’s Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, not in its content (Shantideva leads us through the six perfections of a bodhisattva), but in its ability to inspire us to try to achieve the mind of bodhicitta. The Jewel Lamp is a collection of verses all in praise of bodhicitta, and Khunu Lama Rinpoche’s sole message is that bodhicitta is the very best mind to have. With bodhicitta, all other realizations will come; without it, we can only progress so far. Developing bodhicitta is the best, the most sublime method, and it is the cause for great joy to understand this and see we all have the potential to realize such a mind.

This book is all about the skies of merit we receive from bodhicitta, a subject I never tire of telling people about. The benefits of bodhicitta are boundless; if we tried to explain them all the explanation would never end. We should read books like Khunu Lama Rinpoche’s and Shantideva’s again and again. The first chapter of A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life is purely about the benefits of bodhicitta and it is utterly inspiring.4 Every single benefit brings skies of merit and there are countless benefits.

Reading these verses about bodhicitta is very inspirational for ourselves or others. The verses might not reflect a person’s culture or religion, but they could never alienate anybody. A good heart is everybody’s religion. Bodhicitta is all about cherishing others, giving our life to others. The message these verses give, as all teachings on bodhicitta do, is that the self-cherishing attitude is one that harms others to get what we want, but ultimately that harms us too, whereas the attitude cherishing others brings great joy to others and as a byproduct to ourselves. There is no other way to true happiness.

Therefore, it is extremely beneficial to read the verses that Khunu Lama Rinpoche wrote in The Jewel Lamp and Shantideva wrote in A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life. These are gems, bright lamps that light our way, reminding us constantly that there is no mind more beneficial, more crucial than the mind of bodhicitta.

New Year or a birthday is a time to think of the future. Rather than getting drunk it’s much better to make a strong determination to use every means possible to bring true peace and happiness to our mind by renouncing selfishness and only cherishing others. That is the only New Year’s resolution that makes sense; that is the only worthwhile birthday present. Instead of singing Auld Lang Syne or Happy Birthday, we can recite some of these wonderful verses.

Because bodhicitta is all about benefiting others, every single benefit of bodhicitta only comes about by relying on other sentient beings. Sentient beings are the root of all our good qualities. From them we develop qualities such as patience, generosity, love and so forth. Every single realization a bodhisattva has on the path to enlightenment is purely from the kindness of other sentient beings. Therefore, this precious mind of bodhicitta is supreme in that all good qualities flow from it.

Because there could be no bodhicitta if there were no other sentient beings, we owe every happiness we have to all other sentient beings. When a mosquito bites us, we can feel angry and try to kill it or we can realize that the mosquito, like all other beings, has been our mother again and again in our countless previous lives and has helped us in innumerable ways, and that even now, even as it is biting, it is allowing us to develop patience and that it is merely trying to feed itself and its children. One tiny prick that itches for a little while is not a great sacrifice to make. This is the kind of choice we need to make all the time when we choose between the narrow mind of self-interest and the huge mind of bodhicitta. One brings untold suffering in exchange for a little temporary relief and the other brings untold happiness and skies of merit, rocketing us toward the completely awakened mind of enlightenment.

KHUNU LAMA RINPOCHE’S BIOGRAPHY

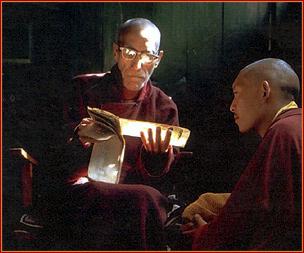

Before we look at some of the verses from Khunu Lama Rinpoche’s book, I would like to mention something of his holy actions, just to get some small idea of his practice.

His life history is amazing, something that we can’t imagine. Even just understanding a little about how he lived can generate incredible devotion. He was a yogi who didn’t have even one single atom of attachment. Whatever action he did—speaking, eating, even just walking—was completely free from even the smell of attachment.

Khunu Lama Rinpoche, Tenzin Gyaltsen, was born in 1894 in the Kinnaur region of Himachal Pradesh, northern India, which shares a border with Tibet. The people there revered him and called him “Khunu” Rinpoche (meaning “precious one from Kinnaur”). When I met Rinpoche in the 1970s, he told me he was not Padampa Sangye5 but his first incarnation was a disciple of Padampa Sangye.

From a very early age, Khunu Rinpoche studied the scriptures, memorizing the Diamond Cutter Sutra as a young boy. He quickly became learned in all aspects of Buddhism, including teachings in Vajrayana, something which is not common at all with Tibetan lay people. At that stage he hadn’t received many tantric teachings, but he had received many Mahayana Sutrayana teachings, including on Shantideva’s Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life.

He spent a long time in Tibet, studying and teaching. This great bodhisattva was exactly like the ancient pandits of the Six Ornaments,6 Nagarjuna, Chandrakirti and so forth, who wrote all the major commentaries on the sutras, the teachings of the Buddha. He even looked similar physically. In Tashi Lhunpo, the seat of the Panchen Lama, and in Lhasa, he studied subjects such as grammar and poetry rather than the traditional texts. Then, in Kham, he studied the most important Buddhist scriptures as well as Sanskrit, and after that he went to Varanasi, the sacred town on the River Ganges in India, to complete his Sanskrit studies. I heard he was an amazing Sanskrit scholar, as well as knowing other Indian languages. I think he even knew a few words of American! He certainly knew the three American states of California, Washington and New York.

Whatever he studied he could remember perfectly. Anything from anywhere, any Buddhist teachings, sutra or tantra, any teachings from other traditions such as Hinduism—nothing was forgotten in the slightest.

When he was living in India in the early years he was exactly like a sadhu, naked except for a piece of red cloth wrapped around his middle, living the simplest possible life. Rinpoche lived among the sadhus and they liked him very much, sometimes offering him food. Even though he lived with them in caves and on the street and looked like them, and even though he obviously had great respect for them, his practice was nothing like theirs.

He had realizations, the experience of the path. He was incredibly rich inside, a great holy being. Day and night, all the time his heart practice was bodhicitta. For us, for myself and ordinary people, the heart practice is the self-cherishing thought, but for beings such as Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen Rinpoche, day and night, the heart practice is bodhicitta. Even though the quality of his knowledge of sutra and tantra, of all the teachings, of the complete path to enlightenment, was as extensive as the sky, still he practiced bodhicitta with his whole heart, renouncing the self and cherishing others. And if Rinpoche gave advice to anybody who came to see him or take blessings from him, this was the main advice.

When Rinpoche traveled from Varanasi to Bodhgaya, he went to the only Tibetan monastery there at the time. I think it had been there since the time when Tibet was independent. He asked for a place to stay, but because they didn’t know him and he looked like a sadhu they didn’t give him a room and so he slept outside on the cement floor. If you have been to a Gelug monastery, you will know that the standard layout is a gate leading to a garden situated in front of the actual monastery, and around the garden is a cement balcony. This is where Rinpoche slept for many days.

Before he was given a room in Bodhgaya by the Tibetan monastery, Khunu Lama Rinpoche often sat in the street and recited texts aloud, in order to benefit the people by purifying their negative karma. He used to sit where people came to circumambulate the Mahabodhi stupa, the great stupa that marks the place where the Buddha was enlightened.

Once, when I was in Mongolia, I visited a traditional Mongolian doctor, somebody who uses urine as a treatment. While there, I noticed an old text on his desk. I was curious and asked if I could see it. The first line said that whoever heard this text would have their negative karma purified. I thought it would be very useful to borrow the text and go outside and read the text aloud for all the beings there, in the same way that Khunu Lama Rinpoche did. Whenever I went into the marketplace with the text and a cushion to sit on, however, it was always filled with shoes. It was a huge area, as big as a central square in a European or American city, but it was completely filled with shoes: Mongolian shoes, Mongolian boots, all sorts of footwear. I couldn’t find one place to sit down. I then thought of doing it outside the doctor’s house but so few people passed by somehow it didn’t happen. I suspect Khunu Lama Rinpoche reciting the texts aloud around the Mahabodhi temple was far more effective.

Throughout his whole life he led an ascetic life, a very pure monastic life, never keeping possessions, no matter how much people offered him. There was no distinction in Rinpoche’s mind with what was offered, whether it was garbage or gold. If he didn’t give it straight back, the offering just went under his bed, like it had no owner. Rinpoche always gave anybody who came to see him Guru Shakyamuni Buddha’s mantra to recite. When Rinpoche lived in Bodhgaya and went to circumambulate the stupa, he used to pick up bodhi seeds and give them as a blessing to the people.

When His Holiness the Dalai Lama went to Bodhgaya, he knew Khunu Lama Rinpoche was there and asked him for teachings on Shantideva’s Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, showing devotion to him as a virtuous friend, as a guru. He received an extensive commentary on it from Rinpoche. I think also His Holiness Ling Rinpoche and His Holiness Trijang Rinpoche studied some poetry and Sanskrit from Khunu Lama Rinpoche.

After Khunu Lama Rinpoche had given teachings to His Holiness the Dalai Lama he immediately become very well known to the Tibetans, just like turning on an electric pump causes a fountain to shoot into the air. Before, nobody had come to receive blessings from him, but afterwards people realized what a great being he was and came to him for blessings in their hundreds, forming long lines from the guest room connected to the monastery that Rinpoche had been given all the way along the street.

People judge by external appearances. Before, people had disregarded him, thinking he was nothing more than a useless sadhu without checking what wisdom he had. If he had had a tall, elegant body and a long, white beard and had worn a smart, long robe they might have decided he was a learned master and a great guru and respected him without His Holiness’ endorsement. They waited days to see Rinpoche but he rarely left his room, not even to eat his one meal a day—he didn’t have a proper kitchen at all—and maybe just coming out for the toilet. I heard he only went for pipi once a day.

There was one monk who was still unable to see him after waiting for many days, so when he saw the monk serving Rinpoche enter his room with his food he snuck in behind the monk. He was kind of angry about being kept waiting for a long time and asked Rinpoche why he had made it hard for him. Rinpoche replied that people who got to see him probably had a relationship with him in previous lives, whereas people who weren’t previous lives’ disciples or who didn’t have a connection with him (or were even angry with him) weren’t able to see him easily.

Although he was not a monk and Rinpoche said in teachings to Tibetans that he lived in the eight lay precepts, actually in practice he kept the 253 precepts of a fully ordained monk. He lived in the precepts perfectly, like a great yogi. In a public place like a market Rinpoche walked looking straight ahead, utterly undistracted by the confusion around him, just as Shantideva recommends in his Guide.

He studied all four traditions of Tibetan Mahayana Buddhism: Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyü and Gelug. I think this happened mainly due to the different presentations of the teachings he received from the lineage lamas. The essential path is the same, the goal is the same; the different teachings all talk about the base, about samsara, about true suffering, and the true cause of suffering. His writings were very sweet, like wonderful poetry. Like the previous great pandits, he was knowledgeable in the five great qualities or excellences, such as diagnosis, hygiene, logic and so forth.

Rinpoche was not only an expert in Buddha’s teachings but also in other religions such as Hinduism. He could explain them all incredibly well, incredibly clearly. Usually when Rinpoche began teaching, if there was time, he would introduce those other religions to show the distortions in their views and how their path didn’t lead to nirvana. Then Rinpoche would start talking about the Buddha’s teaching, about the Dharma and about the four traditions with their different presentations.

Rinpoche had received teachings on emptiness from lamas from all the traditions and although he himself was from the Nyingma tradition he would explain emptiness according the perspectives of all the other traditions and not just his own. In that way he explained it completely correctly. His audience was often composed of lamas from all traditions, although mostly Gelug geshes and incarnate lamas. Rinpoche would not only explain the teachings from one school’s point of view but would also show very clearly each school’s side in his presentation, saying things like, “It is this way according to this school and that way according to that school.” Because his explanations were very clear, without any confusion, everybody was completely satisfied. It was incredible to be learned not only in one school but in all four.

His holy mind was like a vast library, like those they have in the great Tibetan monastic university libraries, with thousands and thousands of volumes. All the teachings that came from the holy mouth of Shakyamuni Buddha were collected into the Kangyur and all the commentaries on his teachings by the great Indian and Tibetan pandits into the Tengyur, with hundreds of volumes in each collection. Rinpoche could remember them perfectly. Even when he was quite old, his mind was still very sharp and clear. Ordinary people like us suffer terribly as we get old; our mind becomes dull and confused and we can no longer remember even the few things we have learnt in our life, and certainly not the more subtle points of the Buddha’s teachings, but Rinpoche could remember and explain any point perfectly.

If Rinpoche’s practice was like a sky at night full of bright constellations, my practice is like stars in the daytime. I requested a commentary on A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life but he didn’t give it; instead he gave me an oral transmission alone in my room. He was so focused that when the postman banged on the door he didn’t even look around but just kept on with the text. The postman knocked quite loudly for a long time. When Rinpoche reached the ninth chapter on wisdom, I think I didn’t have the karma to hear it because I immediately fell asleep. Before I was not even sleepy, but as soon as Rinpoche started to give a commentary on the wisdom chapter, sleep came. That’s how thick my ignorance was. It happened only at that time. I think that there was a lot of negative karma to be purified and consequently it became an obstacle to realizing emptiness. There’s no doubt that I need to do many years of purification.

Later, I was fortunate enough to receive the commentary of A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life from Khunu Lama Rinpoche at the Bodhgaya monastery where the incarnate lamas used to give teachings. At one time, very early on, I lived there with many other incarnate lamas or geshes. I received an oral transmission of Rinpoche’s own Jewel Lamp a couple of times, as well as Atisha’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment when I was in Nepal. I first received the lineage of the Third Dalai Lama’s Essence of Refined Gold from Rinpoche. I remember at that time Rinpoche explained the very difficult concept of dependent arising by simply using his fingers. When he held up his middle and ring fingers, the middle finger was long and the ring finger short, but then he changed the positions of the fingers and the ring finger was then long. Thus, all things depend on all other things. This was simple and marvelous, and that was Rinpoche’s incredible skill at teaching.

At that stage, there were very few Dharma books translated into English, just His Holiness’s Opening the Wisdom Eye and a few more, therefore Rinpoche later advised me to translate A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life into English. He said that teaching bodhicitta would never cause any confusion in people’s minds. Unlike other subjects, it’s a subject that even people with no interest in the Dharma will agree on. Somebody else translated Shantideva’s book before I could start, however.

The last time I saw Rinpoche was in Kathmandu. It was much smaller then, much more primitive, with lots of open fields and fewer houses, and not many monasteries around Boudhanath stupa. He offered me some fruit, taking it from under his table, and advised me that the monks at Kopan Monastery should subdue their minds. (There was no nunnery at that time.) I’m very pleased that after that Kopan has had many excellent teachers who have been able to help the Sangha there do just that, people like Khen Rinpoche Lama Lhundrup, who was a very qualified teacher and a disciple of Lama Yeshe, with incredible knowledge and incredible bodhicitta. Under his guidance the teaching program at Kopan developed quickly, and now Kopan even has its own geshes.

Khunu Lama Rinpoche advised us to always recite Praise to Shakyamuni Buddha.7 This is a prayer that His Holiness the Dalai Lama does daily. This has become a tradition not only at Kopan but in all the FPMT centers, all because of Rinpoche.

After some time, Rinpoche left for the Padmasambhava site in India, where Padmasambhava was born from the lotus in the lake.8 I really wanted to go there and take teachings and commentary on thought training but I hadn’t created the karma. Later, returning to the place where he was born, Rinpoche passed away. He was in meditation when he passed away and stayed in meditation for quite a few days.

The Jewel Lamp

The Jewel Lamp: A Praise of Bodhicitta was written by Khunu Lama Rinpoche as a kind of daily diary, writing a verse a day for about a year. He wrote it in 1959, the year the Chinese invaded Tibet and His Holiness the Dalai Lama fled to India.

Understanding and constantly reminding ourselves of the skies of benefits that bodhicitta brings is unbelievably worthwhile. This is the overall purpose of Khunu Lama Rinpoche’s book, to cause us to feel inspired and joyful that such a mind is possible. For that reason, back in the early 1970s in the courses I led at Kopan Monastery in Nepal, I often used to start the day’s teachings with a quote from The Jewel Lamp. This is where the teachings in this book come from.

The English translation of the book is called Vast as the Heavens, Deep as the Sea: Verses in Praise of Bodhicitta. This is an excellent title, reflecting what Rinpoche says of this precious mind:

[123] Just as the heavens are vast

This bodhicitta is vast.

Just as the seas are deep

This bodhicitta is deep.

Notes

1 Buddhist terms used in this book can be found in a comprehensive glossary on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website. [Return to text]

2 There are six realms in cyclic existence: the three lower realms of the hell beings, the hungry ghosts and the animals and the three upper realms of the humans, demigods and gods. [Return to text]

3 Translated into English as Vast as the Heavens, Deep as the Sea. [Return to text]

4 See Part Two of this book. [Return to text]

5 Padampa Sangye, was a wandering Indian yogi and spiritual master who brought Indian Buddhist teachings to China and Tibet. He lived at the time of Milarepa and taught in the Tingri region of Tibet and is quoted as saying that by holding the guru as more exalted than the buddhas all realizations will come. Lama Zopa Rinpoche says he transformed into a flower as he waited for Milarepa in the Tibet-Nepal region to see if Milarepa would still recognize him, which of course he did. (Rinpoche also cites Milarepa becoming the flower to test Padampa Sangye.) He is author of The Hundred Verses of Advice, published with commentary by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche as The Hundred Verses of Advice: Tibetan Buddhist Teachings on What Matters Most. [Return to text]

6 The six great Indian scholars are Nagarjuna, Aryadeva, Asanga, Vasubandhu, Dignaga and Dharmakirti. [Return to text]

7 See FPMT Essential Prayer Book, 2021, pp. 69–71. [Return to text]

8 Tso Pema, a sacred lake in Himachal Pradesh, India. [Return to text]