Atisha’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment

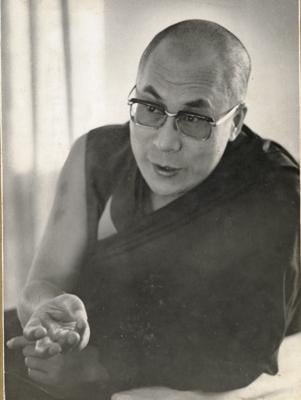

In terms of the lineage of the teachings of the two texts we will be following here, I first received the transmission of Lama Tsongkhapa’s text, Lines of Experience, from Tathag Rinpoche at a very early age, and later from my most venerable tutors, the late Kyabje Ling Rinpoche, who was also the master for my full ordination as a monk, and the late Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche.

The transmission of Atisha’s text, A Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, was quite hard to find at one point, but I received it from my late teacher, Rigzin Tenpa, who may have received the lineage from Khangsar Dorje Chang. Later I received a teaching on it from the late Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche, who gave the transmission in conjunction with Panchen Losang Chögyen’s commentary, which he was able to present almost exclusively by heart.

Lamp for the Path: Verse 1

Homage to the bodhisattva, the youthful Manjushri.

I pay homage with great respect

To the conquerors of the three times,

To their teaching and to those who aspire to virtue.

Urged by the good disciple Jangchub Ö,

I shall illuminate the lamp

For the path to enlightenment.

The line, “Homage to the bodhisattva, the youthful Manjushri,” is a salutation written by the translator who originally translated this text from Sanskrit into Tibetan. At the end of the first verse, the author states his intention for composing this text.

A Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment was composed in Tibet by the Indian master, Atisha Dipamkara Shrijnana. During the reign of the Ngari kings Lhalama Yeshe Ö and his nephew Jangchub Ö, tremendous efforts were made to invite Atisha from India to Tibet. As a result of these efforts, Lhalama Yeshe Ö was imprisoned by a neighboring anti- Buddhist king and actually lost his life, but Jangchub Ö persevered and was finally successful. When Atisha arrived in Tibet, Jangchub Ö requested him to give a teaching that would be beneficial to the entire Tibetan population. In response, therefore, Atisha wrote A Lamp for the Path, which makes it a unique text, because although it was written by an Indian master, it was composed in Tibet specifically for Tibetans.

The meaning of the title

The title, A Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment has profound meaning. The Tibetan term for enlightenment is jang-chub, the two syllables of which refer to the two aspects of the Buddha’s enlightened qualities. Jang connotes the enlightened quality of having overcome all obstructions, negativities and limitations. Chub literally means “embodiment of all knowledge” and connotes the quality of Buddha’s realization and wisdom. Therefore, jang-chub means the Buddha’s enlightened quality of having abandoned and overcome all negativities and limitations (purity) combined with the perfection of all knowledge (realization). Jang-chub chen-po, “great enlightenment,” is an epithet for the Buddha’s enlightened state. The title, A Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, suggests that this text presents the method, or process, by which we can actualize this state of enlightenment.

When we speak about enlightenment and the path leading to it, we are naturally speaking about a quality, or state, of mind. In the final analysis, enlightenment is nothing other than a perfected state of mind. Enlightenment should not be understood as some kind of physical location or rank or status that is conferred upon us. It is the state of mind where all negativities and limitations have been purified, and all potentials of positive qualities fully perfected and realized.

Since the ultimate objective is a state of mind, the methods and paths by which it is attained must also be states of mind. Enlightenment cannot be attained by external means, only through an internal process. As we develop and improve our states of mind, our knowledge, wisdom and realization gradually increase, culminating in our attainment of enlightenment.

The metaphor of the lamp is used because just as a lamp dispels darkness, the teachings in this text dispel the darkness of misunderstanding with respect to the path to enlightenment. Just as a lamp illuminates whatever objects lie in its sphere, this text shines a light on all the various elements and subtle points of the path leading to full enlightenment.

The objects of salutation

The objects of salutation in this verse—the “conquerors of the three times”—are the Three Jewels of Refuge. It is important to pay homage to the Buddha not as just some noble object but in terms of the meaning of jang-chub. The Sanskrit term for jang-chub is bodhi, which conveys a sense of awakening—a state where all knowledge and realization have been perfected. Therefore, when explaining the meaning of awakening, or enlightenment, we can speak about both the process by which this awakening takes place and the state to which awakening brings us; in other words, the means and the fruition.

When we understand enlightenment as a resultant state, we are primarily referring to the enlightened quality of purity—the perfected state where all negativities and limitations have been purified. There is another aspect to this purity, which is the primordially pure nature of the enlightened state. The reason why enlightenment is a perfected state where all obscurations have been purified is because natural purity is its fundamental basis.

When we understand enlightenment as a process, or instrument, by which awakening is experienced, we are referring to the Buddha’s enlightened quality of wisdom. This is the dharmakaya, the buddha-body of reality, the “wisdom body,” or “wisdom embodiment,” of the Buddha, and it is this wisdom that brings about the perfection and purification.

Thus we can understand the significance of the explanations of the different types of nirvana in the scriptures. For example, we speak of “natural nirvana,” “nirvana with residue,” “nirvana without residue,” and “non-abiding nirvana.” Natural nirvana refers to the fundamentally pure nature of reality, where all things and events are devoid of any inherent, intrinsic or independent reality. This is the fundamental ground. It is our misconception of this fundamental reality that gives rise to all the delusions and their derivative thoughts and emotions.

No matter how powerful the false perceptions of reality may be at any given time, if we subject them to scrutiny we will find that they have no grounding in reason or experience. On the other hand, the more we cultivate the correct understanding of emptiness as the nature of reality (and relate this understanding to actual reality), the more we will be able to affirm and develop it, because it is a correct way of perceiving the world. Flawed perceptions lack grounding, experience and reasoning, whereas grounding, experience and reasoning support the understanding of emptiness. Thus we will come to understand that this highest antidote—the wisdom of emptiness—can be developed and enhanced to its fullest potential. This is the understanding of natural nirvana, which makes possible the attainment of the other nirvanas.

What is this natural nirvana that serves as the basis for attaining such purity and perfection? On what grounds do we know that such an ultimate nature of reality exists? We can answer these questions from everyday experience. We are all aware of the fundamental fact that there is often a gap between the way we perceive things and the way things really are. This disparity between our perception of reality and the actual state of affairs leads to all kinds of problems and confusion. However, we also know that our perception sometimes does correspond to reality accurately.

If we go further, we will see that there are two levels of reality. At one level—that of conventional, or relative, reality—worldly conventions operate and our perception and understanding of things and events is based purely upon the way that things appear to us. However, when we question the ultimate status of things and events and the way that they really exist, we enter another realm, or level—that of ultimate reality.

The two truths

Buddhism discusses what are known as the two truths—the truths of conventional and ultimate reality. The concept of two levels of reality is not unique to Buddhism. It is a common epistemological approach in many of the ancient Indian schools. Followers of the non-Buddhist Samkhya school, for example, explain reality in terms of twenty-five categories of phenomena.4 The self [Skt: purusha Tib: kye-bu] and the primal substance [Skt: prakriti; Tib: rang-zhin] are said to be ultimate truths, while the remaining twenty-three categories of phenomena are said to be manifestations, or expressions, of this underlying reality. However, what is unique in Mahayana, particularly in the Madhyamaka, or Middle Way, School, is that conventional and ultimate truths are not seen as two unrelated, independent entities but as different perspectives of one and the same world.

According to the Middle Way School of Buddhism, the ultimate truth, or the ultimate nature of reality, is the emptiness of all things and events. In trying to understand the meaning of this emptiness, we can turn to the teachings of the Indian master, Nagarjuna, who brought together all the various understandings of emptiness into the single statement that emptiness must be understood in terms of dependent origination.

When we talk about emptiness, what we are negating or denying is the possibility of things or events having inherent existence. This suggests that all things and events come into being purely as a result of the gathering of causes and conditions, regardless of how complex the nexus of these causes and conditions may be. It is within this nexus of causes and conditions that we can understand the complexity and multiplicity of the world of experience.

There is great diversity in the everyday world of experience, including our own immediately relevant experiences of pain and pleasure. Even pain and pleasure are not independently existent real experiences; they also come into being as a result of causes or conditions. No thing or event possesses the reality of independence and is, therefore, thoroughly contingent, or dependent. The very existence of all phenomena depends upon other factors. It is this absence of independent status that is the meaning behind terms such as “emptiness” and “the emptiness of inherent existence.”

If we examine the nature of reality more deeply, we will find that within this complex world, there are things and events that have a certain degree of permanence, at least from the point of view of their continuum. Examples of this include the continuity of consciousness and the mind’s essential nature of luminosity and clarity. There is nothing that can threaten the continuity of consciousness or the essential nature of mind. Then there are certain types of experiences and events in the world that appear evident at a particular point but cease to exist after contact with opposing forces; such phenomena can be understood to be adventitious, or circumstantial. It is on the basis of these two categories of phenomena that the teachings of the Four Noble Truths, such as the truths of suffering and its origin, become relevant.

When we further examine this dynamic, complex and diverse world that we experience, we find that phenomena can also be categorized in three ways:

1. The world of matter.

2. The world of consciousness, or subjective experience.

3. The world of abstract entities.

First, there is the world of physical reality, which we can experience through our senses; that is, tangible objects that have material properties.

Second, there is the category of phenomena that are purely of the nature of subjective experience, such as our perception of the world. As I mentioned earlier, we are often confronted by a gap between the way we perceive things and the way they really are. Sometimes we know that there is a correspondence; sometimes we know there is a disparity. This points towards a subjective quality that all sentient beings possess. This is the world of experience, such as the feeling dimension of pain and pleasure.

Third, there are phenomena that are abstract in nature, such as our concept of time, including past, present and future, and even our concepts of years, months and days. These and other abstract ideas can be understood only in relation to some concrete reality such as physical entities Although they do not enjoy a reality of their own, we still experience and participate in them.5 In Buddhist texts, then, the taxonomy of reality is often presented under these three broad categories.

Out of this complex world of reality that we experience and participate in, how do the Four Noble Truths directly relate to our experiences of pain and pleasure? The basic premise of the Four Noble Truths is recognition of the very fundamental nature we all share—the natural and instinctual desire to attain happiness and overcome suffering. When we refer to suffering here, we do not mean only immediate experiences such as painful sensations. From the Buddhist point of view, even the very physical and mental bases from which these painful experiences arise—the five aggregates [Skt: skandha] of form, feeling, discriminative awareness, conditioning factors and consciousness — are suffering in nature. At a fundamental level, the underlying conditioning that we all share is also recognized as dukkha, or suffering.

What gives rise to these sufferings? What are the causes and conditions that create them? Of the Four Noble Truths, the first two truths—suffering and its origin—relate to the causal process of the suffering that we all naturally wish to avoid. It is only by ensuring that the causes and conditions of suffering are not created or, if the cause has been created, that the conditions do not become complete, that we can pre vent the consequences from ripening. One of the fundamental aspects of the law of causality is that if all the causes and conditions a re fully gathered, there is no force in the universe that can prevent their fruition. This is how we can understand the dynamic between suffering and its origin.

The last two truths—cessation of suffering and the path to its cessation— relate to the experience of happiness to which we all naturally aspire. Cessation—the total pacification of suffering and its causes— refers to the highest form of happiness, which is neither a feeling nor an experience; the path—the methods and processes by which cessation is attained—is its cause. Therefore, the last two truths relate to the causal process of happiness.

The Three Jewels: Buddha, Dharma and Sangha

There are two principal origins of suffering—karma and the emotional and mental afflictions that underlie and motivate karmic actions. Karma is rooted in and motivated by mental defilements, or afflictions, which are the primary roots of our suffering and cyclic existence. Therefore, it is important for practitioners to cultivate three understandings:

1. The fundamental nature of consciousness is luminous and pure.

2. Afflictions can be purified—separated from the essential nature of mind.

3. There are powerful antidotes that can be applied to counter the defilements and afflictions.

You should develop the recognition of the possibility of a true cessation of suffering on the basis of these three facts. True cessation is what is meant by the Jewel of Dharma, the second of the Three Jewels. Dharma also refers to the path to the cessation of suffering—the direct realization of emptiness.

Once you have this deeper understanding of the meaning of Dharma as true cessation of suffering and the wisdom that brings it about, you will also recognize that there are different levels of cessation. The first level of cessation is attained on the path of seeing, when you directly realize emptiness and become an arya. As you gradually progress through the further levels of purification, you gain higher and higher levels of cessation. Once you have understood Dharma in terms of both cessation and the path, you can recognize the possibility of Sangha, the practitioners who embody these qualities. And once you have understood the possibility of Sangha, you can also envision the possibility of someone who has perfected all the qualities of Dharma. Such a person is a Buddha—a fully enlightened being.

In this way, you will be able to gain a deeper understanding of the meaning of the Three Jewels: the Jewel of Buddha, the Jewel of Dharma and the Jewel of Sangha. Furthermore, you will recognize the possibility of attaining this state of perfection yourself, and a deep yearning or aspiration to do so will arise in you. Thus, you will be able to cultivate faith in the Three Jewels; faith that is not simply admiration, but something that arises from a deep understanding of the teachings of the Four Noble Truths and the two truths and enables you to emulate the states of the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.

In terms of an individual practitioner’s sequence of realization, first and foremost is the Jewel of Dharma. When you actualize Dharma within yourself, you become Sangha—an arya being. As you develop your realization of Dharma, you reach higher and higher levels of the path, culminating in the attainment of the full enlightenment or Buddhahood. Dharma is the true refuge, Sangha comes next, and finally Buddha.

In the historical context, Buddha came first because Shakyamuni Buddha came into being as an emanation body [Skt: nirmanakaya] and then turned the wheel of Dharma by giving the scriptural teachings. By practicing the Buddha’s teachings, some of his disciples realized the Dharma and became Sangha. Although historically Dharma comes second, in terms of an individual’s sequence of realization, it comes first.

Lama Tsongkhapa’s Lines of Experience

This text, which is also known as the Abbreviated Points of the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment, is the shortest of Lama Tsongkhapa’s lam-rim commentaries expounding the teachings of Atisha’s Lamp.

The style and structure of the genre of teachings known as lam-rim, which can be translated as “stages of the path” or “graded course to enlightenment,” follow the arrangement of Atisha’s Lamp, and the way they are set up allows any individual, regardless of his or her level of realization, to put into practice the appropriate teachings. All the steps of the meditation practices are arranged in a logical, sequential way, so that the practitioner can traverse the path step by step, knowing what to practice now and what to practice next.

The reason that this text is sometimes called Songs of Experience is because Lama Tsongkhapa has distilled all his experience and understanding of the lam-rim teachings into these verses and expressed them in the style of a spontaneous song of spiritual realization.

The term lam-rim has great significance and suggests the importance of the following three points:

1. The practitioner has correct recognition and understanding of the nature of the path in which he or she is engaged.

2. All the key elements of the path and practices are complete.

3. The practitioner engages in all the elements of the practices in the correct sequence.

With respect to the first point, the need for correct understanding of the nature of the path, let us take the example of bodhicitta, the altruistic intention. If you understand the altruistic intention to mean solely the aspiration to bring about the welfare of other sentient beings, your understanding of this particular aspect of the path is incomplete and inadequate. True bodhicitta is a non-simulated, spontaneous and natural experience of this altruistic intention. This is how you may mistake a mere intellectual understanding of bodhicitta for a true realization. It is, therefore, very important to be able to identify the nature of specific aspects of the path.

The second point, that all the key elements of the path should be complete, is also critical. As I mentioned before, much of the suffering we experience arises from our complex psychological afflictions. These emotional and mental afflictions are so diverse that we need a wide diversity of antidotes. Although it is theoretically possible for a single antidote to counteract all our afflictions, in reality it is very difficult to find such a panacea. Therefore, we need to cultivate a number of specific antidotes that relate to specific types of afflictions. If, for example, people are building a very complex structure such as a spacecraft, they need to assemble an enormous variety of machines and other equipment. In the mental and experiential world, we need an even greater diversity of means.

With respect to afflictions of the mind and flawed ways of perceiving and relating to the world, Buddhist texts speak of four principal false views:

1. The false view of perceiving impermanent phenomena as permanent.

2. The false view of perceiving events, our own existence and the various aggregates as desirable when they are not.

3. The false view of perceiving suffering experiences as happiness.

4. The false view of perceiving our own existence and the world as self-existent and independent when they are utterly devoid of self-existence and independence.

In order to counteract these false views, we need to cultivate all the various elements of the path. This is why there is a need for completeness.

The third point is that we’re not just accumulating material things and collecting them in a room; we’re trying to transform our mind. The stages of this transformation must evolve in the right order. First, we subdue gross negative emotions, then the subtle ones.

There is a natural sequence to Dharma practice. When we cultivate a path such as bodhicitta, gross levels of understanding, such as the simulated, deliberately cultivated ones, arise sooner than spontaneous, genuine experiences and realizations. Similarly, we need to cultivate the practices for attaining higher rebirths and other favorable conditions of existence before cultivating those for attaining enlightenment.

These three points—correct understanding of the nature of the path, its completeness and practicing its various elements in the right sequence—are all suggested in the term “lam-rim.”

The origin of the lam-rim teachings: the greatness of the authors

A great number of commentaries came into being on the basis of Atisha’s root text, A Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment. Among these is the genre of writings by the Kadampa masters known as ten-rim, or Presentation of the Stages of the Path, as well as Lama Tsongkhapa’s lam-rim works. These teachings present different skillful means for teaching the Dharma, but they are all grounded in the writings of authentic Indian masters. In the texts of some of the early Indian masters, we find what is known as “the five methods of teaching” or “the five aspects of the skillful means of teaching.”

Later, at Nalanda Monastic University,6 a unique tradition of presenting the Dharma to students developed— the skillful means of “the three purifications” or “the three pure factors”:

1. Ensuring that the teaching being given is pure.

2. Ensuring that the teacher giving the teaching is pure.

3. Ensuring that the students receiving the teaching are pure.

With respect to the second pure factor, even though the teaching being given may be pure, if the teacher giving it lacks the necessary qualities and qualifications, there will be shortcomings in the presentation. It thus became a tradition that before teaching the Dharma, teachers had to receive permission to do so from their own masters. With respect to the third pure factor, even though the teaching and the teacher may be pure, if the students’ minds are not properly prepared, then even an authentic teaching may not bestow much benefit. Therefore, the third pure factor means to ensure that the motivation of the listeners is pure.

Later on, when the Buddhadharma underwent a period of decline in the Nalanda area, it began to flourish in Bengal, particularly at Vikramashila Monastery, where a new tradition in the style of teaching emerged. Here it became customary to begin a teaching by talking about the greatness of the person who composed the text, the greatness and quality of the teaching itself, and the procedure by which the teaching and the listening of that teaching would take place, before moving on to the fourth skillful means, teaching the actual procedure for guiding the disciple along the path to enlightenment.

In those days, the majority of the people sustaining and developing the Dharma in the land of the noble beings, ancient India, were monastics, most notably monks from monasteries like Nalanda and Vikramashila. If you look at the masters from these great centers of learning, you will understand how they upheld the Buddhadharma. They were not only practitioners of the Bodhisattvayana, having taken bodhisattva vows, but also practitioners of the Vajrayana. Nevertheless, the daily life of all these practitioners was very much grounded in the teachings of the vinaya—the teachings on monastic ethics. The vinaya teachings of the Buddha were the actual foundation upon which these monasteries were established and maintained. Two stories illustrate how seriously these great institutions took their monastic discipline.

The great Yogachara thinker and highly realized master Dharmapala, who became the main source of the great inspirational teachings of the Sakya lam-dre—path and fruition—teachings, was a monk at Nalanda Monastery. In addition to being a monk, he was also a great practitioner of Vajrayana and later became known as the mahasiddha Virupa. One day, while the disciplinarian of the monastery was on his rounds, he looked into Dharmapala’s room and saw that it was full of women. In fact, this great mystic tantric master was emanating dakinis, but since monks were not allowed to have women in their room, Dharmapala was expelled from the monastery. It didn’t matter that his infraction was a display of high levels of tantric realization; the fact remained that Dharmapala had broken the codes of monastic discipline and had to go.

There is a similar story about the great Indian master Nagarjuna, founder of the Middle Way School, whom all Mahayana Buddhists revere. At one time, the entire Nalanda area was experiencing a terrible drought and everybody was starving. Through alchemy, Nagarjuna is said to have transformed base metals into gold to help alleviate the famine, which had also affected the monastery. However, the practice of alchemy was a breach of the monastic code and Nagarjuna, too, was expelled from the monastery.

Lines of Experience: Verse 1

I prostrate before you, (Buddha), head of the Shakya clan. Your enlightened body is born out of tens of millions of positive virtues and perfect accomplishments; your enlightened speech grants the wishes of limitless beings; your enlightened mind sees all knowables as they are.

As we have seen, it is traditional first to present the greatness of the author in order to explain the validity and authenticity of the teaching and its lineage. Therefore, the first verse of Lama Tsongkhapa’s Lines of Experience is a salutation to the Buddha. There is a Tibetan saying that just as a pure stream of water must have its source in pure mountain snow, an authentic teaching of the Dharma must have its origin in the teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha. That is why there is such emphasis placed on the lineage of the teachings.

In this verse, then, the author reflects upon the qualities of the Buddha’s body, speech and mind. The qualities of Buddha’s body are presented from the point of view of the perfection of the causes that have created it. The qualities of the Buddha’s speech are presented from the point of view of the perfect fruits of his speech, the fulfillment of the wishes of all sentient beings. The qualities of the Buddha’s enlightened mind are presented from the point of view of its nature and attributes.

In this way, Lama Tsongkhapa pays homage to Shakyamuni Buddha, who was born into the Shakya family and is chief among all humans. When he writes, “I prostrate before you,” he is saying “I bow and touch my head to the lowest part of your body.”

One of the reasons for stating the causes and qualities of the Buddha’s body is to suggest that the Buddha’s enlightened body has not existed since beginningless time. It was not there right from the start but has been created and acquired. The Buddha’s enlightened body did not come into being without cause; it was attained through causes and conditions that are compatible with the actual enlightened state. A detailed explanation of the causal relationship between the various practices and the Buddha’s enlightened embodiments can be found in Nagarjuna’s Precious Garland (Ratnavali).7

The second sentence describes the quality of the Buddha’s enlightened speech as fulfilling the wishes of limitless sentient beings. This explains the actual purpose of attaining enlightenment, which is to benefit other sentient beings. When we become fully enlightened, it is our duty to serve all sentient beings and fulfill their wishes. There are countless ways in which enlightened beings serve sentient beings, such as using their enlightened minds to discern the tremendous diversity of sentient beings’ needs and to display miraculous powers, but the primary medium used by fully enlightened beings to fulfill the wishes of sentient beings is their enlightened speech. The term “limitless beings” suggests that the Buddha uses his enlightened speech in limitless skillful ways.

We also find this respect for the diversity of practitioners’ mental dispositions in the teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha. For example, in acknowledgement of the multiplicity of practitioners’ motives, courage and ethical commitment, we find the three vehicles: the Hearer Vehicle (Shravakayana), the Solitary Buddha Vehicle (Pratyekabuddhayana) and the Bodhisattva Vehicle (Mahayana). Then, from the point of view of the wide range of philosophical inclinations, we find the Buddha’s teachings on the four main schools: Vaibhashika, Sautrantika, Cittamatra (Mind Only) and Madhyamaka, or Middle Way.

According to the Mahayana scriptures, we can understand the teachings of the Buddha in terms of what are known as the “three turnings of the wheel of Dharma.” 8 The first turning of the wheel was at Sarnath, near Varanasi, and was the first public sermon that the Buddha gave. The main subject of this teaching was the Four Noble Truths, in which the Buddha laid the basic framework of the entire Buddhadharma and the path to enlightenment.

The second turning of the wheel of Dharma was at Vulture Peak, near Rajgir, in present-day Bihar. The main teachings presented here were those on the perfection of wisdom. In these sutras, the Buddha elaborated on the third Noble Truth, the truth of cessation. The perfection of wisdom teachings are critical to fully understanding the Buddha’s teaching on the truth of cessation, particularly to fully recognizing the basic purity of mind and the possibility of cleansing it of all pollutants. The explicit subject matter of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras (Prajnaparamita) is the doctrine of emptiness. Then, as the basis for the emptiness teachings, these sutras present the entire path in what is known as the hidden, or concealed, subject matter of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, which is elaborated in a very clear and systematic way in Maitreya’s Ornament of Clear Realization (Abhisamayalamkara).

The third turning of the wheel is a collection of sutras taught in different times and places. The principal sutras in this category of teachings are the source material for Maitreya’s Uttaratantra. Not only do they present emptiness as taught in the second turning of the wheel but they also present the quality of the subjective experience. Although these sutras do not talk about the subjective experience in terms of the subtleties of levels, they do p resent the subjective quality of wisdom and the levels through which one can enhance it and are known as the Tathagatagarbha (Essence, or Nucleus, of Buddhahood) Sutras. Among Nagarjuna’s writings there is a collection of hymns along with a collection of what could be called an analytic corpus, such as his Fundamentals of the Middle Way. The analytic corpus deals directly with the teachings on emptiness as taught in the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, whereas the hymns relate more to the Tathagatagarbha Sutras.

The last line in this verse, “Your enlightened mind sees all knowables as they are,” presents the quality of the Buddha’s enlightened mind. The reference to “all knowables” refers to the entire expanse of reality, which encompasses both conventional and ultimate levels. The ability to directly realize both levels of reality within a single instant of thought is said to be the mark of an enlightened mind. This ability is a consequence of the individual having overcome and cleansed not only the afflictions of thought and emotion but also the subtle traces and propensities of these afflictions.

Lines of Experience: Verse 2

I prostrate before you Maitreya and Manjushri, supreme spiritual children of this peerless teacher. Assuming responsibility (to further) all Buddha’s enlightened deeds, you sport emanations to countless worlds.

In this verse, the author makes salutations to Maitreya and Manjushri and states that they are the two principal disciples of Shakyamuni Buddha. According to the Mahayana scriptures, when the Buddha taught the Mahayana sutras, Maitreya and Manjushri we re the principal disciples present. In the Mahayana tradition, we list eight main bodhisattva disciples of Shakyamuni Buddha.9 However, we should not understand these bodhisattvas as having a physical presence at the Buddha’s teachings but rather as being present on a subtler level of reality. The significance of singling out Maitreya and Manjushri is that Maitreya is regarded as the custodian and medium of the Buddha’s teachings on skillful means and Manjushri is regarded as the custodian and medium of the Buddha’s teachings on the profound view of emptiness.

Lines of Experience: Verse 3

I prostrate before your feet, Nagarjuna and Asanga, ornaments of our Southern Continent. Highly famed throughout the three realms,10 you have commented on the most difficult to fathom “Mother of the Buddhas” (Perfection of Wisdom Sutras) according to exactly what was intended.

In this verse, the author makes salutations to Nagarjuna and Asanga, who became the custodians and progenitors of the two aspects of the Buddha’s teaching: Asanga was the progenitor of the path of skillful means and Nagarjuna was the progenitor of the path of the profound view of emptiness. Lama Tsongkhapa pays homage to these Indian masters as great revitalizers of the Buddha’s teachings. Historically, Nagarjuna came to earth around four hundred years after the death of the Buddha, and Asanga about two hundred years after the death of Nagarjuna. In light of this distance of time between them, the question immediately arises as to the continuum, or lineage, between the Buddha and Nagarjuna and Asanga.

We can understand the continuity of the teachings through successive living masters in human form, such as the lineage of the transmission of the vinaya teachings of ethical discipline, but the transmission of the lineage can also be understood on a more subtle level. For example, the celestial form of the bodhisattva Manjushri had a special connection with Nagarjuna, and Maitreya had a special connection with Asanga. Thus, the great bodhisattvas may sometimes directly inspire the lineage.

When we look at the transmission of the Buddha’s teachings in this way, it obviously raises questions about the status of the historical Buddha. In the Buddhist tradition, there are generally two perspectives on this. One views Shakyamuni Buddha in conventional terms. At the initial stage, he is seen as an ordinary being who, through meditation and practice, attained enlightenment in that very lifetime under the bodhi tree. From this point of view, the instant before his enlightenment, the Buddha was an unenlightened being.

The other perspective, which is presented in Maitreya’s Uttaratantra, considers the twelve major deeds of the Buddha as actions of a fully enlightened being and the historical Buddha is seen as an emanation body. This nirmanakaya, or buddha-body of perfect emanation, must have its source in the subtler level of embodiment that is called the sambhogakaya, the buddha-body of perfect resource. These form bodies (rupakaya) are embodiments of the Buddha that arise from an ultimate level of reality, or dharmakaya. For this wisdom body to arise, however, there must be an underlying reality, which is the natural purity that I referred to before. Therefore, we also speak about the natural buddhabody (svabhavikakaya). In the Mahayana teachings, we understand Buddhahood in terms of the embodiment of these four kayas, or enlightened bodies of the Buddha.

Maitreya makes the point that while immutably abiding in the expanse of dharmakaya, the Buddha assumes diverse manifestations. Therefore, all the subsequent deeds of the Buddha, such as becoming conceived in his mother’s womb, taking birth and so forth are each said to be deeds of an enlightened being. It is in this way that we can understand the connection between the lineage masters of the Mahayana sutras.

Due to the complexity of this evolution, questions have been raised as to the authenticity of the Mahayana sutras. In fact, similar questions arose even in Nagarjuna’s time. In his Precious Garland, there is a section where he presents various arguments for the validity of the Mahayana scriptures as authentic sutras of the Buddha.11 Similarly, in Maitreya’s Ornament of the Mahayana Sutras (Mahayanasutralamkara), there is a section that validates the Mahayana scriptures as authentic sutras. Subsequent Mahayana masters have also written validations of the Mahayana scriptures.

One of the grounds upon which the authenticity of the Mahayana sutras has been disputed is the historical fact that when the Buddha’s scriptural discourses were originally collected and compiled, they did not include any Mahayana sutras. This suggests that Mahayana scriptures such as the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras were not taught by the Buddha in a conventional public context but were taught to a select group of practitioners at a higher and purer level of reality. Furthermore, although there are a few cases where the Buddha taught tantra while retaining his appearance as a fully ordained monk, he taught many of the tantras by assuming the identity of the principal deity of the mandala, such as Guhyasamaja when teaching the Guhyasamaja Tantra. There is no reason, therefore, why these tantras had to have been taught during the time of the historical Buddha.

To understand many of these issues from a Mahayana point of view, it is important to understand Buddhahood in terms of the embodiment of the four kayas. Lama Tsongkhapa, for example, was born three hundred years after the death of the great Atisha. Once when Lama Tsongkhapa was at Retreng, the monastery of Atisha’s most famous disciple, Dromtönpa, he engaged in the deep study and practice of Atisha’s Lamp for the Path. According to his biography, during this period he had vivid encounters with Atisha and Atisha’s two principal disciples, as if face-toface. This didn’t happen just once or twice but several times over a period of months. During this time, Lama Tsongkhapa spontaneously wrote the verses for the lineage masters of the lam-rim teachings.

It is said that it is possible for individuals who are karmically ready and receptive to have encounters with great beings because, even though their physical bodies may have disappeared, their wisdom embodiment remains. Even in our own lifetime there have been practitioners who have had deep, mystical encounters with masters of the past. Only by understanding the nature of buddhahood in terms of the four kayas can we make sense of these complex issues.

Lines of Experience: Verse 4

I bow to Dipamkara (Atisha), holder of a treasure of instructions (as seen in your Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment). All the complete, unmistaken points concerning the paths of profound view and vast action, transmitted intact from these two great forerunners, can be included within it.

In this verse, Lama Tsongkhapa makes salutations to Atisha Dipamkara Shrijnana. Atisha was an Indian master from Bengal, which is near pre sent-day Dhaka in Bangladesh. He had many teachers, but the principal among them was Serlingpa, who came from the island of Serling, the “Land of Gold.” Although there seems to be a place with the same name in the southern part of Thailand, according to Tibetan sources it took eighteen months for Atisha to reach the island by boat from India, which suggests that it was much further away than Thailand. There seems to be a great deal more evidence for Serling having been located somewhere in Indonesia, probably around Java, and, in fact, some reference to the master Serlingpa that has been found in that area.12

Atisha received the instructions on the practice bodhicitta from this master. He then received many teachings on the profound view of emptiness from another master, Rigpa’i Khuchug (Vidyakokila the younger, or Avadhutipa). The general understanding is that until Atisha’s time, wisdom and method (or emptiness and skillful means) were transmitted as two distinct lineages, even though the masters practiced them in union. It was Atisha who unified the two, and the profound view and vast practice were transmitted together from then on.13

From Atisha’s principal student and the custodian of his teachings, Dromtönpa, there evolved three main lineages of the Kadam order.14 The first was the Kadam Shungpawa, the “Kadampa Treatise Followers,” which was handed down through Dromtönpa’s disciple, Potowa, and emphasized study of the major Indian treatises. The second was the Kadam Lamrimpa, the “Kadampa Lamrim Followers,” where emphasis was placed on a gradual approach to the path to enlightenment, relying more on middling versions of the treatises rather than the great ones. Then, a third lineage evolved, the Kadam Mengagpa, the “Kadampa Instruction Followers,” which relied more on actual instruction from the teacher and emphasized the immediate practice of visualization and analytical meditation.

Potowa’s principal student was Sharawa, a very famous master highly respected for his learning of the great treatises. One of Sharawa’s c o ntemporaries was Patsab Lotsawa, the great translator of Chandrakirti’s texts from Sanskrit into Tibetan. It seems that before Patsab Lotsawa’s time, Chandrakirti’s works were not available in the Tibetan language. In fact, when Atisha taught Madhyamaka in Tibet, he used mainly Bhavaviveka’s texts, such as the Heart of the Middle Way (Madhyamakahridaya) and Blaze of Reasoning (Tarkajvala). During Sharawa’s time, however, Patsab Lotsawa began his translation of Chandrakirti’s Supplement to the Middle Way (Madhyamakavatara).

It is said that when Patsab Lotsawa finished the first draft, he presented the manuscript to Sharawa and asked for his opinion. Although Sharawa did not understand Sanskrit, he made critical annotations in key areas of the text and put forward a number of suggestions and corrections. Later, when Patsab Lotsawa compared Sharawa’s comments to the original Sanskrit that he had used for the translation, he discovered that Sharawa had noted the exact areas that needed revision. Patsab Lotsawa was so impressed that he praised Sharawa’s tremendous depth of knowledge of Middle Way philosophy.

Later, after Sharawa received the revised copy of the Madhyamakavatara, he often publicly acknowledged the great contribution made by Patsab Lotsawa in bringing this new literature to Tibet. At one of Sharawa’s teaching sessions, a devotee made an offering of a small piece of brown sugar to each member of the audience. It is said that Sharawa picked up a handful, threw it up into the air and said, “May this offering be to the great Patsab, who made the tremendous contribution of bringing Chandrakirti’s works to the Tibetan people.”

It seems that the Tibetan translators working from Sanskrit sources were tremendously learned and courageous individuals. They were also extremely faithful to the original texts. So much so that even today, modern scholars praise the accuracy of the Tibetan translations. Even though the population of Tibet is fairly small, the teachings of the Buddha have flourished there for almost 1,500 years, and over this time, many highly learned Tibetan masters have composed spiritual texts; not just monks, but lay practitioners as well.

There is a commentary on the Hundred Thousand Verses of the Perfection of Wisdom in the Tengyur, the canon containing all the translated Indian treatises. When Lama Tsongkhapa scrutinized this text, he found so many Tibetan expressions and peculiarly Tibetan ways of saying things, that he concluded that it was not an Indian treatise but an original Tibetan work. He then found corroboration of his conclusion in a catalogue, which listed this text as having been composed by the eighth century Tibetan monarch, Trisong Detsen.

In the salutation in Verse 4, Lama Tsongkhapa refers to Atisha as a “holder of a treasure of instructions.” This is a reference to Atisha’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment. Although the Lamp is quite a short text, it is extremely comprehensive in its subject matter and contains ve ry profound instructions. According to traditional explanations, it is regarded as the instructions of Maitreya’s Ornament of Clear Realization in distilled form.

The main source for Atisha’s Lamp is a section in the second chapter of Maitreya’s text. In stating the sequence of the path and practices, Maitreya talks about cultivating faith in the Three Jewels and the altruistic intention. He goes on to describe taking the bodhicitta vow and engaging in the path by embodying the ideals of the bodhisattva through the practice of the six perfections,15 and then explains how to engage in the cultivation of wisdom where there is a union between calm abiding (shamatha) and penetrative insight (vipashyana). This is how the Tibetan tradition understands the source of inspiration for Atisha’s text.

Lines of Experience: Verse 5

Respectfully, I prostrate before my spiritual masters. You are the eyes allowing us to behold all the infinite scriptural pronouncements, the best ford for those of good fortune to cross to liberation. You make everything clear through your skillful deeds, which are moved by intense loving concern.

In this verse, Lama Tsongkhapa makes salutations to the lineage masters responsible for maintaining and transmitting the practices of the lam-rim teachings. There is a saying attributed to one of the Kadampa masters: “Whenever I teach lam-rim, the great scriptures shudder and say, ‘This old monk is extracting our heart.’”

Lama Tsongkhapa died about six hundred years ago. Of his three main lam-rim texts, the Great Exposition of the Stages of the Path is the most important, but in all three, he presents the elements of the path to enlightenment—the profound view of emptiness and the vast practice of skillful means—in varying degrees of detail, introducing the essential points of these practices in a systematic way such that even today, we can study, contemplate and implement them in our meditation practice.

Regardless of whether the term “lam-rim” or “stages of the path” is used, all traditions of Tibetan Buddhism—the old translation school, the Nyingma, and the new translation schools, such as the Sakya and Kagyü—have equivalent teachings that emphasize the foundational practices. Furthermore, the teachings of all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism can be validated by tracing their origins back to the writings of authentic Indian masters. In the tradition of the Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism, for example, there is the genre of teachings known as terma, or “texts of revelation,” and another known as kama, or “scriptural teachings.” However, even teachings of the revealed tradition must be grounded in those of the scriptural category. In fact, the Nyingma tradition states that the teachings of the revealed texts should be regarded as more for simply channeling one’s focus and sharpening one’s practice.

The greatness of the lam-rim teachings

Lines of Experience: Verses 6 & 7

The stages of the path to enlightenment have been transmitted intact by those who have followed in order both from Nagarjuna and Asanga, those crowning jewels of all erudite masters of our Southern Continent and the banner of whose fame stands out above the masses. As (following these stages) can fulfill every desirable aim of all nine kinds of being,16 they are a power-granting king of precious instruction. Because they collect the streams of thousands of excellent classics, they are indeed an ocean of illustrious, correct explanation.

These teachings make it easy to understand how there is nothing contradictory in all the Buddha’s teachings and make every scriptural pronouncement without exception dawn on your mind as a personal instruction. They make it easy to discover what the Buddha intended and protect you as well from the abyss of the great error. Because of these (four benefits), what discriminating person among the erudite masters of India and Tibet would not have his or her mind be completely enraptured by these stages of the path (arranged) according to the three levels of motivation, the supreme instruction to which many fortunate ones have devoted themselves?

These two verses present the greatness and quality of the lam-rim teachings. Verse 6 explains the nature and lineage of the teaching, while Verse 7 explains its benefits.

1. There is nothing contradictory. One of the greatnesses of the lam-rim tradition is that these teachings enable you to recognize that there are no contradictions in any of the teachings of the Buddha. If you look at the diversity of teachings in the Mahayana scriptures, you will find that certain practices are sometimes prohibited while at other times they are encouraged. If you understand the significance of this diversity, however, you will understand that these teachings are contingent upon the different levels or capacities of the practitioners to whom they have been given. Atisha organized the entire teaching of the Buddha into the three “capacities,” or “scopes,” according to the abilities of different practitioners. Therefore, practices that are restricted for some are encouraged for others. If you don’t bear this in mind, you may develop misconceptions, which occasionally happened in Tibet.

At one time in Tibet, there were practitioners who denigrated and rejected Vajrayana because of their tremendous devotion to and focus on the vinaya, while others, because of their great admiration and enthusiasm for Vajrayana, neglected the practice of ethical discipline. If you understand Atisha’s explanation of how the teachings of the Buddha are organized according to practitioners’ different levels of mind, you will protect yourself from such grave errors.

2. Every scriptural pronouncement without exception [will] dawn on your mind as a personal instruction. The second greatness of the lam-rim is that all the teachings of the Buddha will “dawn on your mind as a personal instruction.” If your understanding of the Buddha’s teachings is limited, there is the danger that you will discriminate between the scriptures, regarding some as relevant to your practice and others as relevant only for academic study. If your understanding is more profound, however, you will realize that the way of the intelligent is to have an overview of the entire Buddhist path. This allows you to appreciate which teachings are relevant at a particular stage in your practice and which are not, while understanding that all the scriptures are instructions that will ultimately be relevant to your own personal practice at some point.

3. Easy to discover what the Buddha intended. The third greatness is that you will easily realize the Buddha’s ultimate intention; that all the Buddha’s teachings can actually converge in your practice. This will allow you to fulfill your spiritual aspirations, whatever they are—higher rebirth, liberation from cyclic existence [Skt: samsara] or complete enlightenment.

4. Protect you…from the abyss of the great error. The fourth greatness of the lam-rim is that it protects you from the “abyss of the great error,” the great mistake of abandoning the Dharma. If you realize that all the Buddha’s scriptures and teachings are relevant to your own personal practice, there is no room for discarding some and adopting others because you realize that actually, you need them all. Therefore, you will not abandon any of the Buddha’s teachings.

This point also relates to the issue of sectarianism. Practitioners sometimes harbor sectarian sentiments because of differences between the four Tibetan Buddhist traditions. If you can understand the unique features of each tradition—their methods of approach, teaching and various types of practices—you will appreciate the value and importance of this variety. It is, in fact, possible for a single individual to integrate all these diverse teachings into his or her personal practice. As the Kadampa masters used to say, “One should know how to uphold the entire teaching of the Buddha, like lifting a square piece of cloth all at once.” 17

Some Mahayana practitioners make distinctions between the Lesser Vehicle and the Great Vehicle, tending to dismiss the Lesser Vehicle teachings, particularly the Theravada. One of the consequences of this is that Theravadins then begin to question the authenticity of the Mahayana tradition. In fact, however, the Pali tradition, from which the Theravada teachings arose, should be regarded as the source of the Mahayana as well, particularly the teachings on the Four Noble Truths and the thirty-seven aspects of the path to enlightenment.18

These are really the foundation and cornerstone of Buddhist practice. To these you add the practices of the six perfections and so forth in the manner of refining certain aspects of these foundational practices, and finally you add the practice of Vajrayana Buddhism. Therefore, even though you can add to it from the bodhisattva and Vajrayana teachings, the Pali canon is really a complete set of teachings in itself. Without the foundational teachings of the Lesser Vehicle, the Paramitayana and Vajrayana teachings are incomplete because they lack a basis.

Question and answer period

Question. If there is a natural nirvana and a luminous, pure, fundamental nature, then what originally leads us to deviate from the pure luminosity for us to suffer from karma, defilements, obscurations and afflictions? How come we do not retain the state of pure luminous natural nirvana through the cycle of births and rebirths?

His Holiness. When Buddhism speaks of the luminous and fundamentally pure nature of mind, or consciousness, what is being suggested is that it is possible for the defilements to be removed from the basic mind, not that there is some kind of original, pure state that later became polluted by defilements. In fact, just as the continuum of our consciousness is without beginning, our delusions are also without beginning. As long as the continuum of consciousness has existed, so too has there been the continuum of delusion—the perception of inherent existence. The seeds of delusion have always been there together with the continuity of consciousness.

Therefore, Buddhist texts sometimes mention innate, or fundamental ignorance, which is spontaneous and simultaneous with the continuum of the individual. Only through the application of antidotes and the practice of meditation can these delusions be cleansed from the basic mind. This is what is meant by natural purity.

If you examine the nature of your own mind, you will realize that the pollutants, such as afflictive emotions and thoughts rooted in a distorted way of relating to the world, are actually unstable. No matter how powerful an affliction, when you cultivate the antidote of true insight into the nature of reality, it will vanish because of the power of the antidote, which undermines its continuity. However, there is nothing that can undermine the basic mind itself; nothing that can actually interrupt the continuity of consciousness. The existence of the world of subjective experience and consciousness is a natural fact. There is consciousness. There is mind. There is no force that can bring about a cessation of your mental continuum.

We can see parallels to this in the material world. According to Buddhism, the ultimate constituents of the macroscopic world of physical reality are what we call “space particles,” which constitute the subtlest level of physical reality. It is on the basis of the continuum of these subtle particles that the evolution of the cosmos is explained. The universe evolves out of this subtlest level of physical reality, remains for a certain period of time, then comes to an end and dissolves. The whole process of evolution and dissolution arises from this subtlest level of physical reality.

Here we are talking about a perceptible and tangible world of physical reality that we can directly experience. Of course, in this world of everyday concrete reality, there will be forces that undermine its existence. The subtle level of physical reality, however, is regarded as something that is continuous—without beginning or end. From the Buddhist point of view, there is nothing that can bring an end to the actual continuum of the subtle level of reality.

Similarly, there are various manifestations of consciousness. These include the grosser levels of thought, emotion and sensory experience, whose existence is contingent upon a certain physical reality, such as environment and time. But the basic continuum of consciousness from which these grosser levels of mind arise has neither beginning nor end; the continuum of the basic mind remains, and nothing can terminate it.

If defilements had a beginning, the question would arise, where did they come from? In the same way, Buddhism does not posit a beginning to consciousness itself, because to do so raises more questions about what led to its creation. As to the question why there is no beginning of consciousness, one can argue for this on the basis of its ever-present continuum. The real argument, however, stems from a process of elimination, because if we posit a beginning of consciousness, what kind of beginning could it be and what could have caused it? Arguing for a beginning of consciousness undermines the fundamental Buddhist belief in the law of causality.

In some Buddhist texts, however, we find references to the Buddha Samantabhadra—the ever-good and ever-pure primordial Buddha. But here we have to understand the concept of primordiality in relation to individual contexts. In this understanding, the fundamental innate mind of clear light is seen as the original source of the macroscopic world of our experience. When the Vajrayana literature describes this evolution process, for example, it speaks of a re verse cycle and a forward cycle.

In both cases, the world of diverse consciousness and mental activity arises from a subtler level of clear light, which then goes through what is known as the “three stages of appearance.” Through this process, there is an understanding that everything arises from this basic nature of clear light mind and is then dissolved into it. So again, our understanding is that this originality is in the context of individual instances, not some kind of universal beginning.

Question. Your Holiness, you spoke of monasteries like Vikramashila, where there was a strict code of ethics and where even highly realized masters could be expelled for breaking a vow. Today, certain rinpoches and high-level masters have been involved in different types of scandals. How come the code of ethics is different today?

His Holiness. One thing that needs to be clearly understood is that the individuals to whom you refer are no longer in the monastic order. People who have broken their vows, particularly one of the four cardinal rules—falsely proclaiming spiritual realizations, committing murder, stealing, and engaging in sexual intercourse—will automatically be expelled from the monastery. They will be expelled even if there are strong grounds for suspicion that they have broken their vows. This applies today as much as it did in the past. However, some of those who have broken their vows still find very skillful and devious means of retaining some kind of dignity and stature.

I always remind monks and nuns, therefore, that the moment they have transgressed their vinaya vows, they should no longer wear their monastic robes. This applies equally to members of all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism: Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyü and Gelug. Within the Tibetan tradition, however, there are two institutions of practitioners— the monastic institution of practitioners with monastic vows and the institution of lay practitioners, who wear different colored robes, don’t shave their heads and have taken only lay precepts, or pratimoksha vows.