Dear LYWA Friends and Supporters,

Thank you for your interest in and support of the Archive.

FPMT News

I have just returned from Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s amazing retreat in North Carolina beautifully organized by the FPMT’s Kadampa Center. You can see and hear the teachings here, incredibly, in English, French, Spanish or Chinese. Transcripts should be posted within a couple of months. Rinpoche’s teachings were truly wonderful.

In the meantime, Mandala Magazine continues to tell the story of the FPMT with its latest issue, just out, on FPMT education. This is the third of four issues detailing FPMT history. You can get copies of the print edition by becoming an FPMT member or sign up for the Mandala e-zine.

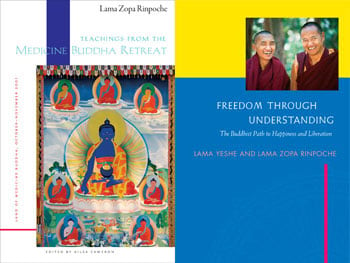

Our New Books Have Arrived Our new books are now in! Teachings from the Medicine Buddha Retreat ($20) which contains extensive teachings from the 2001 retreat at Land of Medicine Buddha covering an amazing range of topics; and Freedom Through Understanding (free) contains Lama Yeshe's and Lama Zopa Rinpoche's first-ever teachings in Europe, September 1975.

Our new books are now in! Teachings from the Medicine Buddha Retreat ($20) which contains extensive teachings from the 2001 retreat at Land of Medicine Buddha covering an amazing range of topics; and Freedom Through Understanding (free) contains Lama Yeshe's and Lama Zopa Rinpoche's first-ever teachings in Europe, September 1975.

Both books will be sent automatically to all LYWA members and FPMT centers. LYWA benefactors will automatically receive Freedom Through Understanding. As usual, the books can also be ordered online. The DVD of Freedom Through Understanding is still in preparation.

New Online Teachings and Audio

Listen online to Rinpoche's teachings during an Amitabha and White Tara retreat at Shakyamuni Center in Taiwan. During these teachings Rinpoche gave the lung of the Amitayus Mantra and the Long Life Sutra. As always, you can read along with the unedited transcripts.

We've made a number of additions to Rinpoche's Online Advice Book. We've added many advices to Lamrim Topics including the section on Guru Devotion, Lamrim Study and Practice, and Preliminary Practices.

Read a teaching from Rinpoche about The Benefits of Having Many Holy Objects, and you can also read many new advices from Rinpoche related to Relics and Holy Objects in the Online Advice Book.

You can read Rinpoche's Praises to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, offered at a long-life puja in 1996. There are also new advices posted regarding His Holiness in the Online Advice Book.

Last month we shared with you excerpts from a forthcoming volume on Karma being produced through our Publishing the FPMT Lineage project. This month we've posted additional excepts from the work-in-progress volume on karma.

And finally, we continue to add to our offerings for Amazon's Kindle reader. The latest title to be added was Rinpoche's Virtue & Reality, bringing the total number of LYWA titles on Kindle to nine.

Educating World Citizens

His Holiness the Dalai Lama will be at the upcoming Mind and Life seminar, Educating World Citizens for the 21st Century, in Washington DC, October 8–9. Student concessions to this wonderful event are available. Please try to make it.

Thank you so much. Please let us know if we can do anything for you. This month we leave you with a talk on the nature of the mind from Lama Yeshe’s last teachings in the West. These were originally published by Wisdom Publications as a transcript entitled Life, Death and After Death but we are preparing a new, complete edition along with DVDs of this special teaching event.

Much love,

Nick Ribush

Director

Some Characteristics of Mind  Each human being has a mind and that mind has three divisions: gross, subtle and most subtle. Similarly, we have a body and that too has three divisions: gross, subtle and most subtle.

Each human being has a mind and that mind has three divisions: gross, subtle and most subtle. Similarly, we have a body and that too has three divisions: gross, subtle and most subtle.

The gross consciousness comprises the five sensory consciousnesses that we use every day. The subtle consciousness can be things like intuitive ego and intuitive superstition. They’re subtle in the sense that we can’t see or understand them clearly. The gross mind is so busy that it obscures the subtle. When the gross mind is no longer flashing, or functioning, the subtle mind has a chance to arise. And that’s one of the functions of Tibetan Buddhist tantra: to eliminate the gross concepts and make space to allow the subtle mind to function. That’s the business of tantra.

Also, the gross mind has no strength, no power. Even though it understands something, it’s relatively weak. The subtle mind has much more power to penetrate and comprehend.

What meditation does is cut the gross, busy mind and allow the subtle consciousness to function. In that way meditation performs a similar function to that of death. Of course, to do the kind of meditation that leads us through the death process we need strong single-pointed concentration.

As you know, Buddhism explains emptiness [Skt: shunyata], the nature of universal reality. We experience emptiness when elimination of the gross, superficial, conventional mind allows it to manifest. Even people who have never heard of emptiness and have no idea of what it is experience a great emptiness in their mind during the death process when all their busy minds dissolve. The moment your gross, crowded concepts stop you feel some space, an emptiness. There’s nothing you actually empty but because your concepts are so crowded, because your mind is so full, when all that content disappears you have an experience of emptiness.

Sometimes when Buddhist philosophers describe shunyata, “blah, blah, blah, blah, blah,” it sounds so complicated. And it’s true; Buddhist philosophy is very sophisticated. Ordinary people don’t understand. “How can I possibly understand shunyata? Nagarjuna says, ‘blah, blah, blah’; Chandrakirti says, ‘blah, blah, blah.’” But when we really bring it back down to earth, all we’re saying is, when you cut your crowded superstitions, the experience comes; when you eliminate all your busy concepts, the experience of shunyata arises, as it does in the death process.

At the moment we’re normally far from reality—from the reality of ourselves; from the reality of all that exists—because we’re enveloped by a heavy blanket of superstition. One blanket of superstition; two blankets of superstition; three blankets of superstition…this blanket, that blanket, another blanket…. All these gross blankets, gross minds, completely built up, like Mt. Meru, like Mt. Everest—so heavy that you can’t shake them off.

Now, I don’t know what methods you normally use, but our business this weekend is to look at the Buddhist method of slowly, slowly removing these blankets one by one: meditation. And in order to do that, we have to understand the characteristic nature of our own mind.

First of all, the mind is not a material substance; it has no shape or color. It’s a kind of formless, colorless energy: the energy of thought or consciousness. Therefore its nature is clean clear and it takes the reflection of phenomena inside. Even thoughts you consider to be heavy and negative still have their own essence, their own clarity, in order to perceive reality or reflect projections.

Also, consciousness, or mind, is like space. The essence of space is its own nature, unmixed with pollution or clouds. The nature of clouds, the nature of pollution and the nature of space are different. Even though pollution pervades space.

The reason why I’m mentioning the negative mind is that we humans have a normal tendency to preconceptions such as, “I’m a bad person, my mind is bad, I’m too negative.” We’re always criticizing ourselves in a dualistic way. Buddhism says that that’s wrong. The characteristic nature of space is not pollution; the nature of pollution is not space. Similarly, the nature of the consciousness is not negative. In fact, the Buddha himself said that buddha, or tathagata, nature lies within each of us and the nature of that is pure, clean and clear.

Also, Maitreya explained that if you put a diamond in kaka, its nature remains different from that of kaka and the nature of the kaka remains different from that of the diamond.

It’s important to know this. A clean clear mind exists within us; the fundamental nature of our consciousness is pure. But while our mind has its own essence of clarity, it’s covered by a contaminating heavy blanket of concepts. Nevertheless, its nature is still clean clear; our consciousness is clean clear. Therefore we have to recognize, “My nature, the essence of my consciousness, is not totally negative. The pure, clean clear nature of my mind exists within me right now.”

Actually, our consciousness has two characteristics: relative and absolute. And the nature of the relative is not negative, not superstition.

Christians might say that the human soul is pure, not negative. It is free of ego conflict, craving desire, hatred and jealousy. Similarly, the relative human consciousness can go from whatever level it’s currently at all the way up to enlightenment. That doesn’t mean ego conflict goes all the way to enlightenment; the dissatisfied, emotionally restless mind never goes through the first, second, third and other bhumis to the tenth and then enlightenment. That doesn’t happen.

The essence of the human consciousness or, we can say, the essence of the human soul continuously goes up, up and up. The negative blanket of superstition never goes up. Each time we clear our negativities they just disappear, disappear, disappear….

So, that’s the relative. With respect to the absolute nature of the human consciousness, or soul, it is totally nondual. In the nonduality of the human mind there’s no mixed up confusion or emotional disturbance. No such thing exists; its nature is always clean clear. Therefore we should all understand that the nuclear essence of each of us our consciousness and that consciousness is not mixed with negativity. It has its own nature, both relative and absolute.

Sometimes we liken the mind to the ocean, where ego conflicts are like waves upon the surface. Concepts arise like waves, shake things up a bit and then subside back into the ocean of consciousness. So the consciousness of each of us is clean clear in nature and our craving desire, hatred and ignorance are like waves upon the surface.

That means we have the capacity not to shake our consciousness. We can hold it without shaking. To some extent we’re capable of that. That’s what meditation does.

Negative motivation is also like a wave. It creates all the confusion, dissatisfaction, pain and misery we experience. All that comes from the negative motivation part of our mind. The root of all our human problems is that wrong place within our mind. It’s most worthwhile to investigate this directly for yourself.

Still, we should understand that our own nature is not totally negative, not totally hopeless. We should respect our own nature, our own purity, our own characteristics. If we do, we’ll then begin to respect others. If you interpret yourself as a big hassle, selfish, totally hopeless and negative, you’ll interpret others in the same way. That’s dangerous.

Also, when you meditate, it’s not your sense perception or sense consciousness that’s meditating. Western people sometimes get confused as to this because they’re so used to the sense world being their only reality; out of habit, the Western mentality is that reality is limited to what you can see, touch and so forth. But the sense consciousness is foolish. It does not have the intelligence to discriminate between right and wrong. That’s why as soon as we open our eyes we’re distracted by sense objects and the flashing of dualistic concepts.

To avoid these foolish old habits of the senses I always recommend that you meditate with your eyes naturally closed.

You can see why. Your mind always wants to see beautiful things; it has already decided. Say you’re planning to go to the market. Before you leave home you start visualizing, “Pears are beautiful this time of year. Apples would be good too.” So when you get to the market and see the pears and apples they appear beautiful because of your preconceptions.

Sense perception is like the Swiss population; consciousness is like the Swiss government. The Swiss government decides, “These people are good; those are bad.” The decision is made. The consciousness is like that. Our preconceptions decide ahead of time what objects are good or bad, so when the sense consciousness contacts those objects it sees them as good or bad. That’s why I say that sense perception is foolish—it doesn’t have its own strength and discrimination.

Also, sense perception sees only the gross reality. It has no way of understanding totality. Modern science tries to understand things by looking at them with ever more powerful microscopes but they can never penetrate their essence that way. Buddhism knows well that you can never understand emptiness in that way.

So, this afternoon we are going meditate on our own consciousness.

Don’t be afraid. “How can I meditate? I don’t know what my consciousness is. This monk’s telling me to meditate on my consciousness, but my problem is that I don’t know what it is. How can I meditate on it?”

Well, say, for example, you’re in a room where you can’t see the sun directly but you can see its rays coming in through the window. From seeing the rays we understand that the sun exists. Similarly, from experiencing our thoughts and motivations we understand that our consciousness underlies them.

Looking at or simply being aware of your thoughts and motivation is good enough for you to be meditating on your own consciousness. Is that clear? I’ll say it again. One way of meditating on your consciousness is simply to be aware of your mind’s view. When you look at your own mind’s view, when you are aware of your own mind’s view, that’s good enough. I call that meditation on your consciousness.

Another way of doing this is to be aware of the essence of your own thoughts. You know the moment you close your eyes some kind of thought is going to arise—just be aware of its essence. I also call that meditation on your consciousness.

Don’t worry whether your thoughts are good or bad—the essential aspect of both is clear, because both good thought and bad reflect phenomena.

When I say “meditation” I don’t mean that you should squeeze yourself. These days there are a lot of misconceptions about what meditation is, especially in the West. Some people think it means you should squeeze yourself; others think it means [Lama shows and example]. Both are wrong. With one, you’re completely distracted; with the other you’re completely sluggish.

Meditation is actually very simple. When you close your eyes, what happens is that your awareness begins to radiate, like a sensitive radar detector. A good radar detector picks up any kind of signal; it notices, it’s aware. Similarly, when we meditate our mind becomes aware; we become very sensitive or totally awake as to what’s going on. That’s what I call meditation—intensive conscious awareness. But I don’t mean that in the conversational sense: “Blah, blah, blah, oh, there’s a light, there’s something else.” It’s not like that.

However, I’d better explain what I mean by conversation. Let’s say we’re supposed to be meditating. We’re aware of what’s going on around us: a car goes by; there goes a truck…. We’re aware, but then what we should not do is start some kind of conversation about what we’ve noticed: “That must be a very nice truck. Perhaps it’s full of cheese for sale. Maybe it an ice-cream truck.” Conversation. That’s what we should not do. We should be aware but in control and not start some kind of internal dialog.

In meditation you’re learning control and how to eliminate the uncontrolled mind. What is it that makes you uncontrolled? It’s your mind making conversation: “He’s like this; she’s like that. He says this; I don’t like it. She says that; I like it.” All this kind of internal chatter is what I mean by conversation. The mind’s constantly reacting but control not reacting.

Somebody calls you a bad person but you don’t react. You don’t make conversation: “She said I’m bad. That hurt my ego, hurt my ego, hurt my ego, hurt my ego….” That’s reacting; that’s an uncontrolled mind, a mind obsessed.

The way I look at it an obsessed mind has two objects: the beautiful object of craving desire or the repulsive object of aversion. And the mind obsessed with either of these objects cannot move away from it. That means you’re not free, not flexible. You’re always thinking, This, this, this, this, this….” That’s what obsessed means. And whether it’s an object of hatred or jealousy or craving desire, an obsessed mind is disturbed. Meditation teaches us to avoid the habit of reacting when an object of obsession appears.

Now, you may ask, what really is the benefit of awareness of your own consciousness as opposed to, say, awareness of a flower? Or your girlfriend or boyfriend? There’s benefit in being aware of the nature of your consciousness because, unlike girlfriends, boyfriends and flowers, consciousness itself has no notion of concrete self-existence. Therefore, the beauty of watching, or being aware of, your own consciousness is that it leads to the breakdown of your heavy blanket, superstitious concepts and to the experience of great emptiness.

In order to solve our problems we need some experience. Intellectual “blah, blah” understanding is not enough. To break down concepts we need a way of gaining experience with our own mind. When we’ve had an experience we know we’re really capable of solving our own problems and this encourages us: “I can do anything I want. I can really solve my problems.” From the Buddhist point of view, that’s the start of human liberation.

Normally we’re too intellectual. We’re always saying, “Good, bad, good, bad, good, bad”; all the time. But when we meditate we stop saying “Good, bad, good, bad, good, bad.” The intellectual good-bad thinking gets stopped. Good-bad thinking is dualistic; it splits your mind. Just be aware; just be conscious.

We should be like the sun or the moon. They don’t think, “I’ll make Swiss people warm; I’ll give Swiss people light.” They don’t do anything like that. So that’s how we should be: intensively aware without any intellectual good or bad. That’s very important.

Maitreya Buddha said that written texts and scriptures are like a bridge. In order to cross a river you need a reliable bridge. Once you’ve crossed you can say, “Bye-bye bridge.” If instead you start thinking, “Oh, this bridge is so kind, this bridge is so kind, this bible is so kind, this sutra is so kind,” so attached to the scripture, it doesn’t make sense.

So what I’m saying is that all the intellectual good-bad is, from a certain point of view, OK. It’s good to be able to discriminate between good and bad. It has some value.

But always going “Good, bad, good, bad, good, bad” doesn’t have much value. You need that kind of discriminating wisdom but at a certain point you have to go beyond it, leave it and just be.

Lama Yeshe gave this teaching in Geneva, Switzerland, in September 1983, his last teaching in the West. Edited from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive by Nicholas Ribush.