Taking teachings

We establish a Dharma connection with someone when, on the basis of the recognition that that person is our guru and we are his disciple, we then receive even a single verse of teaching from him. Making the very first Dharma contact depends on our merit and our past karma.

It is said in the teachings that simply hearing Dharma from somebody doesn’t establish Dharma contact and make that person your guru. You can hear Dharma from someone and study with him without necessarily regarding him as your guru; you make a connection with him, but not a guru-disciple connection. However, once you have taken a teaching by thinking of yourself as a disciple and the other person as your guru, even if it is only a teaching on one verse of Dharma or the oral transmission of one mantra, Dharma contact is established, which means you have formed a guru-disciple relationship, even if you didn’t find the teaching effective for your mind.

With respect to accepting someone as a guru, if from the very beginning you don’t have any wish to make a guru-disciple connection, you can listen to that person’s teaching as if you’re learning from a professor in a university. Generally, you can learn Dharma, especially sutra teachings and explanations, from someone just out of educational interest, to acquire knowledge, like studying with a professor or learning Buddhist history at school. Simply hearing the Dharma from someone doesn’t mean you have established a guru-disciple relationship with that person because you do this all the time in Dharma discussions with your friends. When you discuss points with a friend who knows how to explain them, you don’t regard that person as your guru. You are just helping each other.

While you can listen to Dharma teachings for educational purposes, you need to make the distinction clear from the very beginning as to whether or not you are going to devote yourself to the person as a virtuous friend. However, after some time, if you feel strong devotion in your heart or you see that you have benefited a lot from someone’s teachings and want to establish a guru-disciple relationship, you can then devote yourself to that person as your guru. At that time you can make the decision. Devote means devoting your life to your guru by following his guidance in accordance with the explanations of Guru Shakyamuni Buddha in the sutra and tantra teachings, which is also the way that Lama Tsongkhapa and all the lineage lamas of the four traditions explained and practiced guru devotion. Whether or not you can devote yourself to someone mainly depends on your own attitude, your own way of thinking.

What do you do if in the past you have heard teachings from various people but don’t remember making a particular decision to recognize them as your guru? If you don’t remember any particular benefit to your mind from those teachings and didn’t take them with a determination to establish Dharma contact, you can leave those teachers in equanimity. This means that you don’t need to regard them as your guru but you also don’t need to criticize them. Also, if somebody tells you that you don’t need to devote yourself to him as a virtuous friend you can leave the matter in equanimity. But if listening to someone’s teaching has benefited your mind, if you can, it is better to regard that person as your guru.

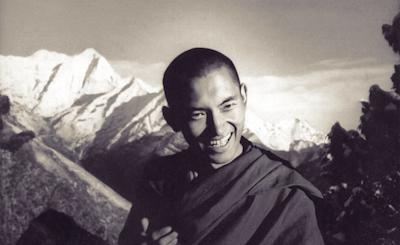

This is the advice the great bodhisattva Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyaltsen gave me when I checked with him about how to regard two of the teachers I had when I was young. When I was a child in Solu Khumbu, I lived part of the time with my mother and the rest of my family in Thangme, the village where I was born, and the rest of the time in Thangme Monastery with my first alphabet teacher, Ngawang Lekshe, who was also one of my uncles. The monastery was about a fifteen-minute walk up the hill from my home.

My uncle and many other monks and lay people were disciples of Lama Döndrub, a Nyingma tantric practitioner, or ngakpa, the head of the monastery, from whom they received many initiations and teachings. Like a puppy, I went along with my uncle and the other monks to whatever was happening. It was a little like going to the movies or to a party. I went along because something was happening and everybody else was going.

At that time I was a small child, perhaps four or five years old, and not yet a monk. During the many teachings, initiations and oral transmissions, I sat on someone’s lap and, of course, slept most of time. I could hear the words but I had no understanding of their meaning. I didn’t even know the names of the initiations. I remember only certain physical activities, such as circumambulating and blowing a conch shell—I blew it but it didn’t make any noise.

I just sat on someone’s lap and watched the faces of the lama, seated on a high throne, and of the monk who read the text. Though I don’t remember a single word of any teaching, I remember very well the lama’s face. Simply seeing the lama benefited my mind. We used to call him “Gaga Lama”—gaga means grandfather in the Sherpa language. I enjoyed looking at the old lama, who looked like the long-life man, with white hair and a long white beard. (He has since passed away and reincarnated.) He was a lay lama, a married tantric practitioner, not a monk. He was a very good lama, with an incredibly kind heart, and I liked him very much. When he did pujas in the morning he would use a drum, and when I heard the drum I used to go to see him. I would open the curtain at the door and wait. The lama would then come down with popcorn or some other present. We should get presents like that again and again.

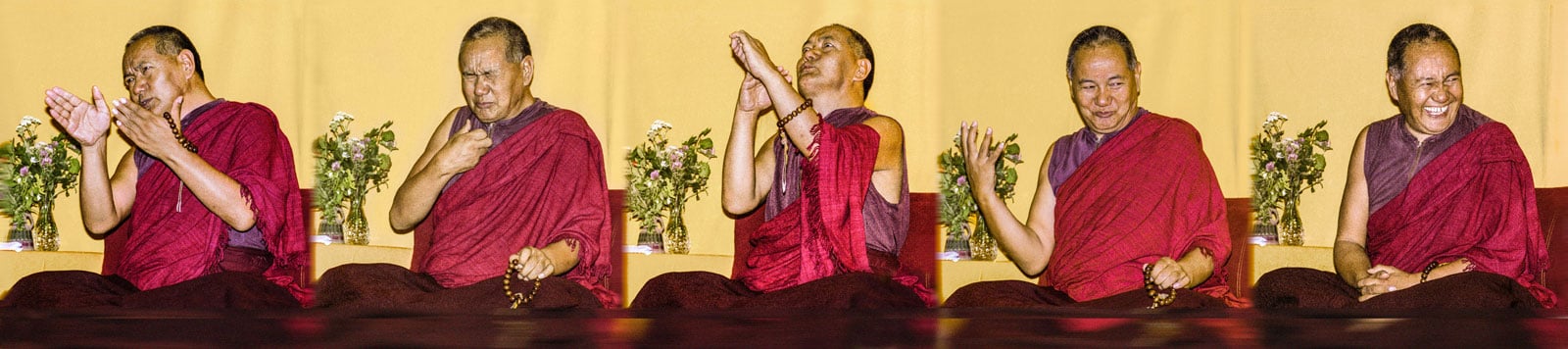

When the lama himself gave a teaching, he would sit very straight and never moved—not like me! He would speak, then always look at a particular spot on the ceiling. Sitting in the lap of one of the monks, I stared at the lama’s face and looked wherever he was looking. I looked at the spot on the ceiling, wondering why he always looked at the same place, but there was nothing there—just the painted wood of the ceiling. At other times a senior monk, one of the lama’s closest disciples, would read the oral transmission from the text, with the lama sitting on the throne, sometimes in the aspect of sleeping. I don’t know why the oral transmission was given in this particular way; it seemed to be the custom.

Sometimes the lama would drink some chang, or barley beer, from a nice glass jar that had probably been offered to him by a Western trekker. The glass would be full of chang, with the barley grains at the bottom, and the lama would use a glass tube to drink from it. While his disciple was reading the text, the lama would sit there, sipping the beer from time to time, and sometimes showing the aspect of sleeping. Because I was in the front row looking at the lama as he drank the chang, he used to pass the jar down to me and I would drink a little.

In Solu Khumbu, Bhutan and other parts of the Himalayas, some of the monasteries had a mixture of monks and married lay practitioners. There was corruption in some of the monasteries, where it had become the custom for monks to drink beer. The lama himself was a lay tantric practitioner and drinking alcohol is not harmful to a highly realized tantric practitioner; it only helps him or her to have quick attainment of the tantric path. Alcohol and other intoxicants cannot harm yogis who have realizations of clear light and the illusory body because they have control over their chakras, winds and drops. They are beyond danger from alcohol and beyond non-virtuous actions.

I remember the part of drinking the beer very clearly but I don’t remember a single word that the lama said, even though I was there during many initiations when the lama spoke a lot about Dharma. It was like receiving an initiation in a dream and not remembering anything when you wake up. Nothing stayed in my mind. Of course, imprints may have been left, but I remember nothing in particular that benefited my mind.

Even though, because I was a child, I had made no particular decision to form a guru-disciple relationship with Lama Döndrub and I hadn’t understood a single word of his teachings, I visualized this lama in the merit field for some years. Later, when Khunu Lama Rinpoche came to Nepal, I went to ask him several questions about guru yoga practice. Even though I had been visualizing this lama as my guru for some years, I asked Rinpoche whether or not I should regard him as my guru. Rinpoche said, “If you remember that the teaching benefited your mind, it is better to regard him as your virtuous friend.” But Rinpoche also said that since I didn’t remember anything at all, I didn’t need to recognize him as my virtuous friend. Rinpoche added that there was no need for me to criticize the lama—I could just leave the matter in equanimity. After that, I didn’t visualize this particular lama in the merit field any more.

Khunu Lama Rinpoche’s advice was that if we have received teachings from somebody, we should check whether or not the teachings have benefited our mind. Even if we didn’t listen to a teaching with the idea of forming a guru-disciple relationship, if the teaching benefited our mind, it is better to regard that person as a virtuous friend, if we can. If we can’t find any benefit to our mind, we can leave the matter in equanimity; we don’t need to criticize that person.

This advice is practical, because it is good to be careful in any case. Even if someone is not our guru, he could still be a holy being, a buddha or a bodhisattva. If the person is a holy being, we create heavy negative karma if we have negative thoughts toward him or harm him. Just to be careful, to protect our own happiness, it is better to leave the matter in equanimity.

In Collection of Advice from Here and There, Langri Thangpa advises, “Since you don’t know other people’s level of mind, you shouldn’t criticize them.”29 Just because someone doesn’t appear to us to have great attainments, it doesn’t mean that this is actually the case. What appears to us and what actually exists are not the same.

The text later says, “If you have generated bodhicitta, it is shameful to criticize others.” As we have taken bodhisattva vows, we shouldn’t criticize others. Also, if, out of anger or another negative mind we criticize someone who has received an initiation from the same vajra guru, we incur the tantric root fall of criticizing a vajra brother. If we aren’t careful, we receive this root fall of the third tantric vow.

It is also mentioned in The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment and other lamrim teachings that your realizations degenerate if you criticize a fully ordained monk, even if you don’t have a guru-disciple relationship with him.

Generally, in the teachings of Kadampa thought training we are advised to practice looking at anybody who mistreats us as our guru. This is done to control our anger and thoughts to retaliate so that we don’t create more negative karma. Any harmful action done to us by others appears as a teaching if we look at them as our guru. The thought-transformation teachings even advise us to look at all sentient beings as our guru or as Guru Shakyamuni Buddha. This is mainly to control our own mind, not so much because the sentient beings themselves are in fact buddhas. If we train our mind in this way, we naturally respect other sentient beings, and since anger and other negative thoughts won’t arise, it protects us from creating negative karma. We train ourselves to think of sentient beings as precious and the source of all happiness, just like the guru. It is similar to practicing pure view in tantra, where we see all sentient beings as the deity.

It is excellent to look at everyone as our guru. But if we can’t manage that, we still have no need to criticize anyone. We shouldn’t criticize anyone, unless it somehow benefits that person.

From Nepal I went to Tibet and lived there for a few years. I was there until about nine months after China took over Tibet. I became a monk in Tibet at the monastery of the great yogi Domo Geshe Rinpoche, the guru of Lama Govinda, who wrote The Way of the White Clouds and Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism. I was ordained as a novice monk by the abbot, Thubten Jinpa, a very good, very subdued geshe. I also can’t remember anything that the abbot said at the time of my ordination. The only thing I can remember clearly is sitting in front of the abbot and other people giving me a lot of khatags.

My first retreat, which I did in Tibet just before escaping, was on Lama Tsongkhapa Guru Yoga, but I had no idea at all what I was doing. I hadn’t received any teachings. Though I now regard him as a guru, Losang Gyatso, the monk who took care of me in Tibet and helped me to become a monk in Domo Geshe’s monastery, didn’t explain any Dharma to me. He just verbally taught me Praise to the Twenty-one Taras, which I didn’t know by heart before that. When I checked with Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche, Rinpoche said I should regard him as a guru because he verbally taught me the prayer, even though he didn’t specifically give me any Dharma teachings or vows. Losang Gyatso gave me a text on Lama Tsongkhapa Guru Yoga but at the time I didn’t have the capacity to understand it. I believe that I finished reciting 100,000 migtsemas. I then did a tsog offering, which Losang Gyatso had arranged beautifully. That same night we escaped from Tibet.

At that time the Communist Chinese were publicly torturing the heads of monasteries, leaders of the people and anybody who had a name as somebody important. When we heard that they were within a day or two of reaching the monastery where we lived, Pema Chöling, a branch of Domo Geshe’s main monastery, we escaped that night through Bhutan to India. I went with Losang Gyatso together with some monks from Pema Chöling and some other monks that we met on the road. From Pema Chöling, which is near the border of Tibet, we had to cross only one mountain to reach Bhutan. There we met up with many monks and benefactors, then went to Buxa Duar in West Bengal.

Buxa Duar was the concentration camp where Mahatma Gandhi and Prime Minister Nehru were imprisoned when India was under British rule. This is where the monks from Lhasa and other places who wanted to continue their study were sent. Those who didn’t want to study went to work building roads in different parts of India, especially at first along the border with Tibet. There were about 1,500 monks at Buxa. Because of the heat and unhygienic conditions, many monks got TB and many of them passed away.

We didn’t have to stay in Buxa, as Domo Geshe Rinpoche had also founded a branch monastery in Darjeeling. As this monastery was well established, we didn’t have anything to worry about. However, while all the other monks from Domo Geshe’s monastery were allowed to go to the Darjeeling monastery, the head policeman of the camp, Tashi Babu, who was Indian but possibly of Tibetan origin, wouldn’t allow Losang Gyatso and me to go to Darjeeling. I don’t know why he didn’t let us go. He had no reason to stop us—he wasn’t being paid any money to do it. I thought that maybe the abbot or one of the staff of Sera Je Monastery went to the police, but that doesn’t seem to have been the case. Whether it was the buddhas or the Dharma protectors, something made that policeman stop me from going away and made me stay at Buxa. I think it might have been the action of the special deity, because that is how I got the chance to meet my perfect gurus, Geshe Rabten Rinpoche and Lama Yeshe. I had this chance and the chance to study a little of the philosophical subjects and hear lamrim teachings through the kindness of this policeman.

Before I met Geshe Rabten Rinpoche, Losang Gyatso took me to another lama that he somehow knew. I went to him for teachings for an hour or so for just two or three days and studied with him one verse from the very beginning of dura, the preliminary debating subject. After two or three days, for some reason—perhaps because I belonged to Sera Je and he was from Drepung Monastery—he said, “I can’t be your teacher. You should go to Geshe Rabten, who is from Sera Je College.” He said that Geshe Rabten Rinpoche was a very good teacher and that it would be good for me to take teachings from him.

I also checked with Khunu Lama Rinpoche about whether I should regard this lama as my guru. Rinpoche said that generally it is good to regard such a person as a guru, but since he had said that he couldn’t be my teacher, which was like giving me permission not to regard him as a guru, Rinpoche said that I didn’t need to devote to him as a guru. Again, Khunu Lama said that I also didn’t need to generate any negative thoughts toward him. Because of Rinpoche’s advice, I don’t include this lama among my gurus.

When I asked Kyabje Chöden Rinpoche about this point, Rinpoche said that the teacher also has to recognize you as a disciple.

It was very kind of this lama to introduce me to Geshe Rabten Rinpoche, a great hidden yogi. Geshe Rabten was very learned, a good teacher, pure in morality, very kind and good-hearted, and renowned in all the monasteries. Geshe Rabten Rinpoche’s way of devoting to his virtuous friends was also incomparable. Geshe Rabten had two root gurus, His Holiness Trijang Rinpoche and the lama who took great care of him in his home monastery. Geshe Rinpoche’s way of guiding disciples, as well as his way of teaching and talking, was unbelievably skillful, exactly in accord with each disciple’s wishes and capabilities.

That I now have a little bit of interest in meditation is by the kindness of Geshe Rabten Rinpoche because he was the first guru to explain Dharma to me. Since Geshe Rinpoche was talking a lot about calm abiding, my first interest was in calm abiding.

The first time I went to see Geshe Rabten Rinpoche to take teachings, I went with Losang Gyatso and took a tea offering in a thermos and some other offering. Geshe Rinpoche and many disciples were crowded into a courtyard outside one of the buildings, a long prison block with many gun-slots in the walls and doors, and windows covered with bars and barbed wire. The courtyard was also not a very pleasant place. All the walls were barbed wire, so you couldn’t lean on them without cutting yourself. And all the monks’ seats were crowded tightly together, with Geshe Rinpoche sitting up on a high seat.

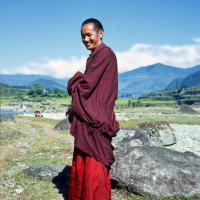

Lama Yeshe was sitting down below Geshe Rabten, with a big pile of texts on his table. Because I was very small and had the name “incarnation,” Lama lifted me up and put me on Geshe-la’s bed. During the teaching, Lama sometimes looked at Geshe-la’s face with great devotion. I could see that he was extremely devoted to Geshe Rabten.

I took teachings like this several times, but Geshe Rabten had many disciples and was very busy. As he had to teach various classes to different levels of monks, including many senior ones, he didn’t have much time to teach me on my own. Geshe-la sent me to one of his disciples, Gen Yeshe, a very good debater, who was from the same area in Tibet as Geshe Rinpoche. From Gen Yeshe I heard for the first time about the kindness of the mother from the seven techniques of Mahayana cause and effect.30 There were no texts, so Gen Yeshe explained it orally and I wrote it down in my own writing, as I hadn’t learnt how to write properly from anyone. He also taught me a little about the visualizations in Lama Tsongkhapa Guru Yoga.

Gen Yeshe was very learned and very humorous and joyful. He was also a great teacher, similar to Lama Yeshe. However, my time with Gen Yeshe was very short. Rather than be at Buxa, he wanted to live an ascetic life and go on pilgrimage around India. He didn’t stay at Buxa long but left to wander around India. After some time he became a lay person, then showed the aspect of sickness and passed away in India.

I then went to Lama Yeshe for teachings. Chöphel (pronounced “Chombi”), the leader of my class and later a cook at Kopan Monastery, first brought me to take teachings from Lama Yeshe, as he had been taking teachings from him for a long time. Geshe Rabten Rinpoche actually wanted me to take teachings from one of his close disciples, Geshe Thubten, a well-educated and very good monk, but somehow my karma was different. My manager, Losang Gyatso, also had Geshe Thubten in mind.

Even though my manager was saying that I should study with Geshe Thubten, Chombi insisted that I take teachings from Lama Yeshe. We used to walk together sometimes around the hills or go to the river to bathe, and one day he simply led me to the gate of the monastery. I said, “I don’t want to go any further! I don’t want to receive teachings from Lama Yeshe. I want to go back home.” Chombi said, “Oh, come, come, come.” He insisted so much that I went a few more steps with him. Again I said, “No, I don’t want to go.” I walked a few more steps, then again said, “No, I don’t want to go. I want to go back.” Carrying on like this, I finally ended up outside Lama Yeshe’s room. Again I told him, “I don’t want to go. I want to go back.”

I waited outside while Chombi went inside to see Lama. I hadn’t brought any offerings with me as I had simply accompanied Chombi on a walk. Chombi himself piled up some rice in a bowl, offered it with a scarf and a few rupees and asked Lama if I could take teachings from him. I think Lama asked whether Geshe Rabten Rinpoche had agreed to it or not and Chombi said that he had, even though that wasn’t exactly what Geshe Rabten Rinpoche had in mind. As Chombi had already made the offering, I reluctantly went inside.

Lama Yeshe had a tiny room in the jungle, with a window at the back with a nest of ants. There was almost nothing in the room—it was practically empty. There was a small stove made out of an Indian butter tin with a hole at the bottom for firewood and only two pots. There were also some texts covered with plastic and a hard split-bamboo bed with some Bhutanese woven material on top. That’s all. It was extremely simple.

That first day, because I bore the label “reincarnate lama,” Lama again put me next to him on his bed. I think that Lama putting me on his bed at the very beginning might be why there has been the karma for me to sit on a throne.

I didn’t understand anything at all, maybe because I hadn’t come with a good motivation. Lama was teaching about cause and effect, but debating the subject. He was so quick that the question came in my mind, “Why can’t he teach slowly?” The next day was better, but that first day I couldn’t understand anything at all.

I think there was strong karma from many past lives for Lama Yeshe to guide me. I didn’t come with the intention of receiving teachings and was even rejecting the idea, but the karma was very strong. My impression is that even though I really didn’t want to go that first day, there was strong karma from past lives, so that past-life karma led me.

His Holiness Serkong Dorje Chang, an embodiment of Marpa who lived and passed away in Nepal and has now reincarnated, is another of my virtuous friends. Many FPMT students met and received blessings from Serkong Dorje Chang and he also ordained one as a nun. I visualize Serkong Dorje Chang in the merit field, even though I never received any particular initiations or formal teachings on a particular text from him.

While I was at Buxa Duar I heard many stories about Serkong Dorje Chang performing the actions of a yogi, peculiar actions that didn’t fit the minds of ordinary people. Serkong Dorje Chang would simply disappear; sometimes his attendants would lose him. Rinpoche would be there one minute and gone the next, suddenly appearing somewhere else. I heard that in the early times Serkong Dorje Chang had been imprisoned by the Nepalese authorities for something that wasn’t his fault. Even though nobody had opened the door, Rinpoche was not in his prison cell the next day; he was back home in his monastery.

After Lama and I went to Nepal I had a great wish to meet Serkong Dorje Chang. One day I went to visit Rinpoche on top of the hill at Swayambhunath with Lama, Zina Rachevsky, our very first Western student, and Clive, from London, one of Zina’s friends from Darjeeling who was teaching Lama English. Zina was very interested in meeting lamas from the different traditions. When Lama and I were living with her, as she was always going to see lamas, Lama compiled a list of Dharma questions for her to ask.

When we reached the top of Swayambhunath hill we asked around for Serkong Dorje Chang. When we got to the two-story house we’d been directed to, a very simple-looking monk was coming down the steps. I asked him where Serkong Dorje Chang was and the monk said, “Oh, wait here a little while.” The monk went off to urinate, I think, then returned and went back upstairs.

We then went upstairs to meet Serkong Dorje Chang’s manager. Later, when we entered the room to see Serkong Dorje Chang, the monk sitting on the bed turned out to be the simple monk we had seen coming down the steps.

Normally, if you asked Serkong Dorje Chang questions about Dharma, he wouldn’t answer. But if it was the right moment and you had good karma, Rinpoche would show a peaceful aspect and maybe talk for a while. Otherwise, Rinpoche might show a wrathful aspect.

It must have been quite an auspicious day, because when Zina asked a question about how to practice guru devotion, Rinpoche gave a brief but unbelievably profound teaching. The teaching was so deep and my obscurations were so thick that I couldn’t comprehend what he said at all. His voice was magnificent but the only thing I understood was that if the guru is sitting on the floor, you should think that Guru Shakyamuni Buddha is sitting there. That’s all I could understand. I was supposed to be the translator but the teaching was so rich that I didn’t understand it.

In the Western way, Zina then asked Rinpoche to read something from the texts that he had in front of him, but Rinpoche refused, saying, “No, no, I’m completely ignorant—I don’t know anything.” But at the beginning of the interview he had given incredible advice.

Rinpoche would often say things like this and act as if he knew nothing. However, after being in his presence I have not the slightest doubt that Rinpoche was Yamantaka. Even though in appearance Rinpoche seemed to be an ordinary monk, if you sat in front of him you became certain that he was Yamantaka. You didn’t need to use any logical reasoning or quotations. No matter what aspect Rinpoche showed, it didn’t change my conviction that he was Yamantaka.

As soon as anyone entered the room, Rinpoche could immediately see every single thing about them, past, present and future. He could even tell me the dreams I had had some days before. Sometimes, when people came to ask Rinpoche for observations, before Rinpoche started to throw the dice, Rinpoche would tell the person about their life. One man from Mustang, who had killed someone, came to Rinpoche for an observation and before he threw the dice Rinpoche said, “Oh, you killed a human being.” The man was shocked, because he didn’t expect to have his life revealed.

People seeing Rinpoche circumambulating the Swayambhunath Stupa would likely think he was just a simple monk, someone who didn’t know much more than how to recite OM MANI PADME HUM. But if it was the right moment, Rinpoche would suddenly tell one of the other people circumambulating something like, “You’re going to die in three years—you should purify yourself by doing prostrations to the Thirty-five Buddhas.”

In the early times in Tibet, Serkong Dorje Chang gave initiations and teachings. Rinpoche had taken his geshe degree at the same time as the great yogi Trehor Kyörpen Rinpoche, from Drepung Monastery. One time Serkong Dorje Chang was to give a Kalachakra initiation. It had already been announced and many people were planning to come. His Holiness Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche was very worried about how Serkong Dorje Chang was going to give even the preliminary lamrim teaching to the people.

His Holiness Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche, one of His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s gurus, was the son of the previous incarnation of Serkong Dorje Chang, one of the great yogis of the Gelugpa tradition, who passed away in Tibet. A highly attained yogi of the completion stage of tantra, Serkong Dorje Chang was highly respected; he was one of the few lamas permitted by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, who was very strict, to have a wisdom consort for quick completion of the tantric path.

Serkong Dorje Chang is the incarnation of Marpa, Milarepa’s guru; Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche is the incarnation of Marpa’s son, Darma Dodé; and Tsechok Ling Rinpoche, who in his past life was the guru of His Holiness Ling Rinpoche, His Holiness Trijang Rinpoche and many other high lamas, is the incarnation of Milarepa. Serkong Dorje Chang mentioned this directly from his own holy mouth to one of the monks from his monastery. One evening as this monk was accompanying Rinpoche back to the monastery after finishing a puja in a benefactor’s house, Serkong Dorje Chang said to him, “In reality I’m Guru Marpa, Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche is the son of Marpa and Tsechok Ling Rinpoche is Milarepa. We are actually like this.” When Rinpoche showed the aspect of being happy, he would tell his monks stories of his past lives and other amazing things.

His Holiness Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche fled Tibet with the incarnation of his father, Serkong Dorje Chang. When they reached the place in southern Tibet where Milarepa had built the nine-story tower they were surrounded by Chinese and there seemed to be no way to escape. Serkong Dorje Chang, Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche and Changdzö-la, their attendant, who had been offered to Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche by his father, slipped quietly inside the tower, then went upstairs, where there were statues of Marpa and Marpa’s secret mother, Dagmema. Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche had a damaru that had belonged to Marpa and a mala that had belonged to the wisdom mother. Rinpoche kept them with him all the time. Rinpoche then offered the damaru to Marpa and the mala to Dagmema, with the prayer, “Father and Mother, please understand our situation. Whatever happens in my life is up to you.” It was an intense situation, with the Chinese army all around and no way out.

At that time Changdzö-la, who heard Rinpoche call Marpa and Dagmema “Father and Mother” discovered why His Holiness Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche is called thug-tse, “the holy heart-son.” He is Marpa’s son. His Holiness the Dalai Lama also used to address Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche as “thug-tse.”

Also, many years ago in Tibet, when His Holiness the Dalai Lama was invited to China, Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche and some other learned geshes accompanied His Holiness. When His Holiness and his party reached Kham, many people came looking for Marpa’s son to get blessings. Changdzö-la, not knowing that they meant Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche, said, “We’ve never heard of Marpa’s son—there’s no such person in our group.” Changdzö-la told me that he later found out that many people called Rinpoche by that name.

To return to the story: Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche told me that the night before Serkong Dorje Chang was to begin the Kalachakra initiation, he instructed him on how to explain the lamrim as the motivation for the initiation.

The next day Serkong Dorje Chang talked about the eight freedoms and ten richnesses as the motivation for the initiation, but when he meant to say “long-life god” he instead said “long-life man.” One learned geshe who had come for the initiation was disappointed. Just because he thought Rinpoche had given a wrong explanation of what a long-life god is, the geshe left; he didn’t take the initiation. His Holiness Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche told me that during the actual Kalachakra initiation, Rinpoche gave an unbelievable, extensive commentary.

So, while great yogis might show some mistakes, at the same time they show things that ordinary people cannot. His Holiness Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche often used to say that he thought Serkong Dorje Chang embodied the meaning of “yogi.”

Serkong Dorje Chang showed the aspect of being epileptic in his later life, but no matter what aspect he showed externally, Rinpoche was a great yogi. The Tibetan government would ask Rinpoche to do important wrathful pujas. Because Rinpoche was the real Yamantaka, he was qualified to do those wrathful pujas that are dangerous for ordinary people to do. On the days of the pujas, the monks would request, “Please, Rinpoche, don’t have a fit today.” They were scared that Rinpoche would have an epileptic fit at an important part of the puja and everything would fall apart, because Rinpoche was the main one performing the concentration to quell the evil-doer and transfer their consciousness. On those days Rinpoche would say, “Hey, if I can’t do even something like this, how can I be called ‘Dorje Chang’?” And on those days Rinpoche wouldn’t have a fit.

Every morning before Rinpoche drank his first cup of tea, he liked to make a tea-offering to the protectors. He would also offer tea in a big bowl to all the lineage lamas of the lamrim by reciting the requesting prayer Opening the Door of Realization from Jorchö. And whenever Rinpoche traveled, he would always carry with him a small photo frame with pictures of all his gurus; he kept it tucked inside his dongka.

One time, years ago, His Holiness the Dalai Lama sent the Lower Tantric College monks to consecrate the Boudhanath stupa because some fire had come from the top of it. I think somewhere in the texts it mentions that if something evil is happening in Nepal, fire will come from the stupa to dispel the negative forces. Also, since it is because of Boudhanath stupa that Buddhism was spread and preserved in Tibet for so many years,31 the consecration of the stupa is important. During the puja, His Holiness Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche was the main master and Serkong Dorje Chang and I were also there. Serkong Dorje Chang took the framed picture of all his gurus, with brocade around it, out of his dongka and put it on the table to be consecrated as well.

When Lama and I first arrived in Nepal from India with Zina, we all stayed in the Gelugpa monastery in Boudhanath for about a year. The original building was built by a Mongolian lama, but the monks who lived there came from a monastery in Tibet founded by Kachen Yeshe Gyaltsen, a great pandit and yogi who was a tutor of the Eighth Dalai Lama. He established the monastery with pure vinaya practice and discipline, though I don’t think there was much debating of philosophy.

About three months after we arrived the monks from the monastery invited us to take part in a nyung nä they were planning to do. The benefactor of the nyung nä had invited one of his gurus, a Nyingma lama from Swayambhunath, to give the Eight Mahayana Precepts, but the monks didn’t want to take the Mahayana ordination from that lama because you have to regard as your guru anyone from whom you take the Eight Mahayana Precepts. The monks instead invited Serkong Dorje Chang to the monastery to give the precepts.

We went downstairs early in the morning to begin the nyung nä. When Serkong Dorje Chang came in, he sat on one of the monks’ cushions, not on the throne. Someone brought him the text for the Eight Mahayana Precepts, which he opened. As the motivation Rinpoche then said, “If you want to practice Dharma, if your guru tells you to lick kaka, you should immediately get down and lick it, while it’s still hot.” Rinpoche made accompanying slurping noises. Rinpoche then said, “That is the real Dharma practice!”

After Rinpoche had said this, he closed the text and left. That was all the motivation he gave for the Eight Mahayana Precepts. There was no repeating of prayers—nothing! He said this, then left.

As Rinpoche hadn’t performed the actual ceremony, we took the Mahayana ordination of the nyung nä from the altar, even though there were other lamas there.

I found this teaching extremely powerful for my mind, like an atomic bomb. It was just a few words, but it was heavy with meaning. Rinpoche gave the very heart of the practice. Because that teaching was so beneficial, I feel devotion to His Holiness Serkong Dorje Chang. Even though that was the only teaching I ever received from him, I regard Rinpoche as my guru and visualize him in the merit field.

Do we need to formally request someone to be our guru?

You don’t normally need to request someone to be your guru. Forming a guru-disciple relationship depends more on your making the decision in your mind than on your personally asking that person’s permission to attend an initiation or teaching. In Tibet, if you were planning to attend an initiation or teaching from a lama for the first time, the tradition was to go see that lama and ask his permission to attend. You would just quickly ask, “Can I take these teachings?” The lama would then check and accept or reject your request.

Before listening to teachings from someone for the very first time, if there’s time, you can make a request to attend the teachings; however, because there are often hundreds or thousands of people involved, there’s not usually enough time for each person to personally request permission. For example, thousands of people receive teachings from His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Not everybody can go to see His Holiness and ask, “Please be my guru.”

However, when His Holiness Ling Rinpoche gave some particular initiations and teachings, it seems that people would go to ask permission to attend them. They didn’t go to see Rinpoche, but just asked his attendant whether they could receive the initiation.

After the teaching has happened and the connection has already been made, there is no need to ask the person to be your guru. This would be like requesting your mother to be your mother or your father to be your father after you had already been born.

Taking initiations

Simply sitting in a line of people during an initiation doesn’t mean that you receive the initiation and the person giving it becomes your guru. Receiving initiation has to do with the mind, not the body. It’s a mental action.

Just being where an initiation is being given doesn’t mean that you receive the initiation and establish Dharma contact. If you don’t take the initiation, just being there doesn’t establish Dharma contact. Many other creatures—flies buzzing around, ants, fleas and other bugs, and sometimes dogs—can also be physically there while an initiation is happening and hear all the words of the explanations of the visualizations. If you simply sit there and don’t do the visualizations, you haven’t received the initiation. Even if you drink a whole bucket of vase water and eat a mountain of tormas, that alone doesn’t mean you have received the initiation.

In certain cases you might have to be present at an initiation to ensure harmony within a Dharma center, where various lamas are invited because students have different wishes and different karma or because of your responsibility within an organization. If you have no intention of following the person giving the initiation as a guru and don’t do the visualizations, simply sitting there in the group of people doesn’t mean that you receive the initiation. If you know what to do and how to think, there will be no confusion. Your mind, not your body, takes the initiation.

Meditation centers in the West generally invite many different lamas to give teachings. One reason for this is that people have different karma. Each time a lama comes, there are different people who have a karmic connection with that particular lama, and even though many other lamas might come to the meditation center, until that particular lama comes, those people don’t meet the Dharma. Each individual student has to be clear from the beginning whether or not he wants to make Dharma contact with a particular lama.

It’s possible that someone could sit in an initiation and not do any of the visualizations at all but that the lama could do the meditations in relation to that person, such as visualizing them as the deity. The initiation can then become the giving of a blessing to that person. The person can receive the blessing but doesn’t necessarily take the lama as a guru because he hasn’t done the visualizations explained. He receives the blessing, but in the manner of having a puja done to give him protection. If from his side he hasn’t done the visualizations or regarded the lama as his guru, he hasn’t received the initiation.

However, if you decide to take an initiation, do as much as you can of the meditations and visualizations explained, which are always based on seeing the lama and the deity as inseparable. At the end generate faith that you have received the initiation. If you do all this, you receive the initiation and establish a Dharma connection with the person who has given it. You should regard that person as your guru because he has planted in your mind the seed of Dharma, the seed of the four kayas of Highest Yoga Tantra, which ripen your mind to practice the path. Even if you had no particular thought to accept the person as your guru, if you do the meditations and visualizations, you have taken the initiation and that person becomes your guru.

If you treat an initiation like a horse race, with everyone racing to get there first, problems can arise later, especially if you haven’t heard complete lamrim teachings on guru devotion or if these teachings somehow haven’t touched your heart. If you later regret taking the initiation and the lama becomes an object of criticism, almost like your enemy, you will burn many eons of merit and unnecessarily make your life difficult. After a connection has been made, things won’t work out if you damage the root of your practice through not having thought deeply about the meaning of the lamrim.

Taking vows

I think that you should regard as your guru anyone who has granted you a lineage of vows: refuge, pratimoksha, bodhisattva or tantric vows, or even the Eight Mahayana Precepts. Whether that person is lay or ordained, Tibetan or Western, male or female, you must regard him or her as your guru. If you do the visualizations when you take the vows, I would say that you have established a Dharma connection with that person, even if at the time you didn’t have any thought of forming a guru-disciple relationship.

With respect to the vows and ordinations you’ve already taken where, because of your lack of understanding of the lamrim, you didn’t regard the person as a guru, you have to regard those teachers as your guru as you have made Dharma contact. You mightn’t have known the important points of this practice of guru devotion, but if you have taken the Eight Mahayana Precepts or any other vows, which are all based on refuge, from someone, I think you should regard that person as your guru.

As I have already explained, at the beginning you can listen to teachings without having to regard a teacher as your guru but I don’t think you can do the same thing with vows or initiations. I don’t think that any valid lamas would say that you can take a full initiation from someone without regarding him as your guru; I don’t think that they would accept that in relation to any of the vows either.

If you have taken gelong or getsul ordination, you have to regard as your guru not only the abbot but also the lobpön, or preceptor. If you have taken gelong ordination, you have to regard as your guru both the lekyi lobpön, who gives the twenty-one pieces of advice to the gelongs (though sometimes the abbot does this) and also the sangdön lobpön, who comes outside to ask you questions about whether you have any particular sicknesses and so forth and to give you advice.

When I took gelong ordination, His Holiness Ling Rinpoche was the abbot; His Holiness Serkong Tsenshab Rinpoche was the lobpön; and the chant leader at the Tibetan Temple in Bodhgaya, a very good old monk, was the sangdön lobpön.

Some geshes say that you have to regard even the monk who reads the sutra at sojong as your guru because he is asked to say that prayer as the representative of Guru Shakyamuni Buddha, but such a person doesn’t commonly have to be regarded as your teacher.

If you take the oral transmission of even one verse of a prayer or one mantra, the person giving it also becomes your virtuous friend—not simply by your hearing the oral transmission but by your taking it to receive the blessing.

Otherwise it would mean that we could achieve enlightenment without a guru—which is impossible. It would mean that we could achieve realizations of the lamrim and tantric paths without needing a guru to grant initiations and vows. There is no one who has ever achieved enlightenment in that way.

In the strict interpretation, you should regard as your virtuous friend even someone who teaches you the mudras found in tantric practices or how to draw mandalas. In the monasteries in Tibet, strict practitioners of lamrim would learn such things only from someone with whom they wanted to have a Dharma connection. However, it’s possible to discuss such things as friends, without any particular recognition of a guru-¬disciple relationship.

Should we regard our alphabet teacher as our guru?

Tibetans traditionally regard the person who teaches them the alphabet as their guru. I include both of my alphabet teachers, who passed away many years ago, among my gurus, for example. Both of them were my uncles and both were fully ordained monks at that time. I had two alphabet teachers because I was naughty.

The uncle who first taught me the alphabet, Ngawang Lekshe, lived in the Thangme monastery, very close to my home. I was very naughty and didn’t study well. I think I understood the alphabet, apart from one syllable that I couldn’t seem to learn. I was like the arhat Chudapanthaka, or Small Path, who couldn’t memorize the two syllables “si” and “dam.” When he learnt “si,” he forgot “dam”; and when he learnt “dam,” he forgot “si.” 32 My teacher used to teach me the alphabet in the courtyard and when he went inside our room to prepare food I scratched out the letter that I was finding hard to learn.

When I was put in the monastery by my mother I often used to run back home. After one or two days my mother would again send me back to the monastery with somebody, who would carry me up the hill on his shoulders. After one or two days there I would again escape. When my teacher went inside our room to cook our food after teaching me the alphabet outside, I would quickly run back home. I think it was because at home I got to play all the time; there was nothing particular I had to do.

At home I had some friends I would play with. One of my best friends, who played with me every day, was mute, and there were a few other children. We would play in a field where there was water and would come back home when my mother shouted from the window that lunch was ready. We would return for the meals.

Many times when we played, I would sit on a higher seat and pretend to be a lama and my friends would pretend to be disciples or benefactors. Near our house was a large rock with mantras carved into it and I would sit a little way up the rock and pretend that I was giving initiations to my friends by putting things on their heads. Since we didn’t know the prayers we would just make some noise. The one pretending to be the benefactor would make an offering of food by mixing some earth with water and putting it on a small piece of flat stone. We would pretend to do pujas and things like that.

One time when everything was covered with snow, I was playing in the courtyard, blowing through a plant and pretending I was playing a trumpet in a puja, when the thought came to escape from my teacher. I ran down the mountain. At that time I was wearing some pants that my mother had given me. I hadn’t had pants before—they were a kind of one-piece overall made of very cheap prayer-flag fabric dyed red; at that time in Solu Khumbu good cloth was very hard to find. Inside where the top and bottom met, there were a lot of lice and eggs.

I didn’t know how to open the pants to go to the toilet. So that day when I ran from the monastery all the way down to my mother’s house, I came down with kaka in my pants. When I arrived, my mother was outside with some people. She then took off all my clothing and cleaned everything up.

Because the monastery was close to my home and I kept running away every few days, my mother sent me to another part of Solu Khumbu, Rolwaling, an isolated place reached only after crossing dangerous snow mountains. Looking back now, I can see it was extremely kind of her.

I lived in Rolwaling, which has many holy places of Padmasambhava, for seven years with my second alphabet teacher, Aku (which means uncle) Ngawang Gendun, who taught me to read. We would get up at dawn, recite our prayers, then read texts. One time we had to read The Diamond-Cutter Sutra over and over. We sometimes had to read all of the One Hundred Thousand Verse Perfection of Wisdom Sutra for benefactors who requested us to read it.

Except for meal times and when I would go outside to pee, when I got to goof off a little bit, I read texts almost all day long. We would read the whole afternoon, stopping some time before sunset. One time when I thought my teacher had gone far away I stopped reading and just turned some pages over. When he came back after ten or fifteen minutes he could see I hadn’t actually been reading but had been sitting there just playing around, so he beat me. It was normal to be beaten with dried bamboo but when my teacher hit me on the head with the bamboo stick it shattered into pieces. He then spanked and beat me here and there.

I don’t remember what I had done, but one time when it was raining, he made me take off my clothes and put my mouth in the water where it had collected on the flat stones in the courtyard. Another time (again I don’t remember what I had done), my teacher took me outside and rubbed my backside on some nettles. I don’t remember feeling much pain or really suffering.

Anyway, looking back now, I think I experienced unbelievable purification from my teacher getting me to read all those texts and from beating me. Even though I had no understanding of the meaning of the texts, I definitely think that repeating the texts over and over again for many months left positive imprints on my mental continuum. Due to the kindness of those teachers in my childhood in letting me read those texts and thus leave positive imprints and due to all their beatings, I think I purified many heavy negative karmas.

Western students have asked whether there is any difference between learning the English alphabet and the Tibetan alphabet. In Tibet, students regarded their alphabet teacher as a virtuous friend because the teacher usually taught the alphabet so that the students could learn Dharma—and this was also the student’s motivation for learning it. There was normally a Dharma motivation from both sides. This is different from learning the alphabet in a Western school, but if you learn the Tibetan alphabet with the intention of studying Dharma, I think you should regard your Tibetan teacher as your guru.

Should you look at the teacher who taught you the ABC as your guru and visualize him or her in the merit field? According to Lama Yeshe’s definition, the person who teaches you the alphabet becomes your guru if you learn the alphabet with the aim of practicing Dharma. I think it’s not necessary to visualize in the merit field the teacher who taught you the English alphabet because her reason for teaching you was not so that you could practice Dharma. Of course, there is nothing wrong with looking at your mother, father, teacher or whoever else taught you the alphabet as your guru. It’s profitable to do so.

When we were in Buxa, this issue was discussed in relation to two schools there, where some of the monks started to learn English and Hindi. There were three teachers altogether: a Chinese-looking Tibetan, who taught English to the young incarnate lamas and the monks; an Indian shopkeeper; and a Ladakhi monk. At that time there was discussion as to whether to regard these teachers who were teaching the English and Hindi alphabets as gurus. According to Lama Yeshe’s explanation, we didn’t need to regard them as gurus since we weren’t learning English and Hindi for Dharma purposes.

The importance of visualizing every guru

Since correct devotion to the virtuous friend is the root of the whole path to enlightenment, we need to take good care of our relationships with all the gurus with whom we have had direct Dharma contact. When we don’t practice correctly in relation to even one of our gurus, even if all our other gurus are happy with us, if we don’t change our attitude and confess our mistake, we can’t generate realizations no matter how much we meditate.

It is important to have a good relationship and practice correctly with every single one of our gurus. If we practice guru devotion correctly only with those we like and ignore or practice incorrectly with those we don’t, there is no way we can subdue our mind and achieve realizations of the path, no matter how much practice or retreat we do. If we leave a guru out of our visualization because we dislike or can’t relate to him, we don’t have the chance to develop guru devotion toward that person, and no matter how much devotion we feel toward our other gurus, nothing will happen in our mind. We should keep count of the number of gurus we have and visualize all of the gurus with whom we have made a Dharma connection when we meditate on guru yoga in the lamrim or in Six-Session Guru Yoga, Lama Tsongkhapa Guru Yoga or Guru Puja.

As the lamrim teachings mention, if somebody asks us how much money we have in our purse, we’re immediately ready with the answer but if somebody asks us how many gurus we have, we’re not sure. That’s because we always count our money carefully and take more care of it than we do our gurus. Being unclear about the number of gurus we have shows that we haven’t paid much attention to the practice that is the root of the path to enlightenment.

If we leave out from our visualizations even one guru with whom we have Dharma contact, no matter how much we practice, study or do retreat, there’s no way to really subdue our mind and no way to achieve realizations of the path. It is vital not to leave anybody out; otherwise, we can’t develop our mind. We shouldn’t forget even the gurus who have given us just the oral transmission of a verse of teaching or a mantra, let alone those who have given us vows and initiations.

The importance of visualizing every single guru is illustrated by the story of Drubkhang Gelek Gyatso, a highly attained lamrim lineage lama who wrote many extensive scriptures on sutra and tantra. Je Drubkhangpa’s biography, which explains how he practiced lamrim, especially bodhicitta, is very interesting and very inspiring. The cave where he did many years of meditation is high on the mountain above Sera Monastery in Tibet.

When Je Drubkhangpa began to meditate on lamrim, he spent many years meditating, but nothing happened. There was no change in his mind, no realizations. Wondering if something was missing from his practice, he went to consult his root guru.

His guru said, “When you visualize the merit field, have you forgotten anyone with whom you have made a Dharma connection? Go back and check whether you have left out any of your gurus.”

When Je Drubkhangpa checked, he found that he had left out the teacher who had taught him the alphabet when he was still a child living at home. Je Drubkhangpa saw his alphabet teacher, a monk who later broke his vows, as bad-tempered and cruel. Because he didn’t like this teacher, Je Drubkhangpa found it difficult to develop devotion toward him and didn’t visualize him among his other teachers. He visualized all his other teachers in the merit field.

When Je Drubkhangpa went back and explained this to his guru, his guru advised, “This is the problem. This is why you haven’t been able to have any realizations during all these years. You must now completely change your attitude and meditate on this guru as your root guru in the center of the whole merit field. Visualize him as Lama Losang Thubwang Dorje Chang,33 the principal figure of the merit field. Until you develop devotion, look at him as the essence of the entire merit field.”

As soon as Je Drubkhangpa did this meditation, everything changed. He started to develop devotion toward this teacher and realizations then came very easily, one after another, like falling rain.

Je Drubkhangpa’s story is a great teaching for us, showing us the importance of ensuring that no guru is left out of our visualization of the merit field so that we develop devotion toward all our gurus. If we have used the methods for intensive purification and for collection of extensive merit and have done many retreats but still nothing is happening to our mind, it means that something is wrong; there’s something missing in our practice. We then have to check our practice of guru devotion. We might not have analyzed well exactly how many gurus we have and left one out or we might not have paid attention to the heavy negative karmas we have created in relation to particular gurus. If we find that we have left out one of our gurus, we have to change the situation by putting strong effort into developing devotion to that guru. Otherwise, nothing will happen; our listening, reflecting and meditating won’t be successful in transforming our mind into the lamrim path.

We should remember all those with whom we have a guru-disciple relationship and visualize them all in the merit field, even those with whom we have made mistakes in the past and created negative karma through breaking samaya, renouncing the relationship and so forth. We should now change our attitude and, looking at every one of them as an embodiment of our own deity or Shakyamuni Buddha, devote ourselves correctly to them with thought and with action.

We should feel that all our gurus are the same in essence, just different in aspect. This is one of the meditation techniques to develop guru devotion. We don’t find many faults in some of our gurus and feel much devotion toward them; however, with one or two of our gurus we might find it difficult to generate devotion because we see them as full of faults. As explained by Kachen Yeshe Gyaltsen, a technique to develop devotion also toward that guru is to think that he is the embodiment of the guru for whom you feel the strongest devotion and in whom you don’t find faults. After you see that guru as buddha, you then think that your other gurus are manifestations of that guru.

If we wish to achieve enlightenment quickly we have to know the important points of guru yoga practice, such as the necessity of visualizing all our gurus. Not understanding how to practice or making mistakes in our practice will block our realizations.

How many gurus should we have?

It is not necessary to have just one guru, like having one boyfriend or girlfriend. Westerners sometimes think that they can’t have many gurus but should have just one. Or they take initiations and teachings but still think that they haven’t met their guru. This is a mistake.

You can have many gurus or you can have just one guru and be satisfied with that. It depends on how well you are able to practice guru devotion. Lama Atisha, who had 152 gurus, said that he didn’t do any action that wasn’t wished by all those gurus. Somebody who has enough merit and knows how to practice guru yoga can have hundreds, millions or billions of virtuous friends. There is no danger in such a person regarding anybody as their virtuous friend. Kadampa Geshe Sungpuwa, while traveling on pilgrimage from Kham to Lhasa, would take teachings from anyone he met along the way who was giving teachings. If a crowd had gathered by the side of the road to receive teachings from someone, Geshe Sungpuwa would go there, listen to the teaching, and then regard that person as his guru. Ra Lotsawa and Dromtönpa, on the other hand, had very few gurus.

There is a debate about whether it is wiser to have few or many gurus. The conclusion is that if you can practice guru devotion well, you can devote yourself to everyone who gives you a teaching and have hundreds of gurus without any problems. But if you can’t, it’s better to have fewer gurus, so that you create less negative karma—the more gurus you have, the more obstacles you create. You will make Dharma contact with one person, then generate negative thoughts toward him; you will then make contact with another virtuous friend, then again generate negative thoughts toward that person. For some people, the more gurus they have, the more obstacles they create to their enlightenment.

If you find guru devotion difficult to practice, you should make Dharma connections only with teachers with whom you think you can maintain guru devotion. By having fewer gurus, you will create fewer obstacles to the happiness beyond this life up to enlightenment. Basically, it depends on your own capacity, on your own mind. If you have a lot of superstition and always look at the negative rather than the positive, you should be careful.

There is a saying that if you can’t practice guru devotion, you receive as many negativities as the number of gurus you have. But there are also advantages in having many gurus—if one guru doesn’t have the lineage of a particular teaching or initiation that you need to benefit yourself or others, you can take it from another guru. In this way you can receive all the teachings.

It is fine to plan to have only one guru in your life but you may not be able to always be in the same place as that guru and he may not always have time to teach you. If you don’t find other gurus to study with, your understanding may not develop quickly.

Generally, whether you have one guru or a hundred, how quickly you generate real understanding of Dharma and realizations of the path depends on your individual skill and practice.

Who is the root guru?

With respect to the root guru, anyone from whom you have directly received teachings can be called a root, or direct, guru, whereas the lineage lamas are indirect gurus. However, a common definition of the root guru is the one among all your gurus who has most benefited your mind, the one who has been the most effective in directing your mind toward Dharma.

You don’t necessarily have just one root guru; you can have more than one. Among Lama Atisha’s 152 gurus, for example, he regarded five as his root gurus, including Lama Suvarnadvipi and Dharmarakshita. Lama Suvarnadvipi was the guru from whom Lama Atisha received the complete teachings on bodhicitta over a period of twelve years and in whose presence Lama Atisha generated bodhicitta. Whenever he heard someone say the holy name of Lama Suvarnadvipi, because of the power of his devotion, Lama Atisha would immediately stand up from his seat and, with tears in his eyes, place his hands together in prostration on his crown.

In the case of tantric deity practice, the lama you visualize as the root guru in the sadhana is the one from whom you have received the initiation of that deity. If you have received the same initiation from many lamas, you choose the one among those many lamas who has most benefited your mind. Again, you can have more than one root guru.

We have to meditate and discover that the root guru is not separate from our other gurus. The root guru is one with all our other gurus and all our other gurus are embodiments of our root guru, the one who has most benefited our mind. Meditating in this way helps us to generate the same strong devotion to all our gurus, especially if there are any toward whom we have difficulty generating devotion. By meditating in this way, we stop the thought of seeing faults in those particular virtuous friends, which is the heaviest obstacle to developing our mind in the path to enlightenment. If we are able to look at all our other gurus as we do our root guru and generate the same strong devotion toward all of them, there will be no obstacles to realization. Realizations of the path to enlightenment will fall like rain.

Before we decide to devote ourselves to someone, we need to be very careful. We should examine, or check, well at the very beginning before we decide to rely upon someone as a virtuous friend. Once the Dharma contact has been made, however, examining is finished; it is then wrong to continue the examination. Once we have made the Dharma connection, we have to regard that person with a completely new mind, with the determination that he is Guru Shakyamuni Buddha or the deity we are practicing. After we have established a guru-disciple relationship, we correctly devote ourselves to the virtuous friend as explained by Buddha in the sutra and tantra teachings. If we are practicing tantra, we practice the special guru yoga as explained in tantra.

Generally speaking, there’s a responsibility from both sides once the Dharma connection is made. Guiding the disciple is the teacher’s responsibility and, after Dharma contact has been made, correct devotion to the virtuous friend is the disciple’s responsibility. Once we have made the Dharma connection, by receiving a teaching with the recognition that that person is our guru and we are his disciple, we have to live our life with a totally new attitude toward that person and not with our old thoughts. We have to look at him in a totally different way; we have to look at him as a buddha. Even if we saw faults in that person before, from the time of establishing Dharma contact, we have to change our way of looking at him. We have to decide at the very beginning that no matter what happens, we are going to practice guru devotion toward that person. We have to change our concept and look at him as a buddha. In this way, our mental continuum is protected from the negative karmas and pollution of degenerating samaya. Otherwise, we will be totally destroying ourselves. Every day we will be creating hell.

Once we have listened to teachings with recognition of someone as our virtuous friend, whether that person is lay or ordained, male or female, there can be no question of changing our mind. It shouldn’t be that as long as the person is sweet to us and we like him, we regard him as our virtuous friend but when he is no longer sweet to us we don’t regard him in that way.

Be careful at the beginning, because once the relationship has been established nothing can be changed unless the guru gives you permission to no longer regard him as your guru. Once the relationship has been formed there is no heavier karma than giving up the guru, renouncing the guru as an object of devotion. It is a much heavier negative karma than committing the five uninterrupted negative actions. Among all heavy karmas, this is the heaviest.

This applies once a guru-disciple relationship has been formed, whether or not we have taken a tantric initiation from that person—though I’m sure the negative karma is greater if the person is our vajra guru. Also, even if we haven’t taken a tantric initiation from the lama that we have given up, if we have taken tantric initiation from other lamas, we have to keep the tantric vows, and we should be very careful not to receive the heavy negative karma of the first tantric root fall,34 which is the heaviest. Otherwise, no matter how many eons we practice mahamudra or other secret, profound paths, we will have no result. It will be extremely difficult to develop our mind once we make a mistake in this important point of guru devotion practice.

We have to be clear about what we’re going to do at the very beginning so that there will be no problems or confusion later. As Lama Yeshe used to say, we have to make it “clean clear.” We need to be clear about the way we intend to study Dharma teachings, whether as part of a guru-disciple relationship or as in a university. Otherwise, if we are not clean clear in the beginning before we establish Dharma contact, we may later create much negative karma. When problems happen later, we will be like an elephant sunk in mud. We will have already accumulated so much negative karma that it will be difficult to finish purifying it.

If we’re not clear about the very root of the path to enlightenment, the very root of all realizations, no matter how much we study or understand Dharma, it will be difficult for us to complete the practice and really experience the path. If we’re not clear about this point, our life will become a mess.

I thought to mention these points about who to regard as guru as it may help people who are unsure about the practice of guru devotion to have a clear understanding in regard to their past and future relationships.

Notes

29 See The Book of Kadam, p. 594, or The Door of Liberation, p. 116. [Return to text]

30 The six causes are recognizing all living beings as our mothers, remembering their kindness, wishing to repay their kindness, developing the affection that sees them as lovable, cultivating compassion and the special attitude, and the one effect is bodhicitta. [Return to text]

31 The four men who completed the building of the Boudhanath stupa were later born in Tibet as the Dharma king, Trisong Detsen; his minister, Selnang; the great yogi, Padmasambhava; and the abbot, Shantarakshita. For further details see The Legend of the Great Stupa by Keith Dowman, Tibetan Nyingma Meditation Center, Berkeley, 1973. [Return to text]

32 See Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, pp. 106–12, for the long version of this story. (Page references in these notes are to the 2006, blue-covered edition.) [Return to text]

33 Lama Losang Thubwang Dorje Chang is the principal figure of the Guru Puja and Jorchö merit fields. Lama refers to the root guru, Losang to Lama Tsongkhapa, Thubwang to Shakyamuni Buddha, and Dorje Chang to Vajradhara. The main figure of Lama Tsongkhapa has Shakyamuni Buddha at his heart, who in turn has Vajradhara at his heart. [Return to text]

34 The first tantric root fall is despising or belittling one’s guru. [Return to text]