I was attending His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s teachings in Bodhgaya in 1981 when news of his mother’s death arrived. The Tibetans became very distressed, weeping and wailing all over the place, but at his next discourse, His Holiness looked at them bemused and said words to the effect of, “People, get a grip. What are you crying for? She was the mother of the Dalai Lama, had a long and privileged life, did millions and millions of manis and other practices, and has been reborn in a pure land. There’s nothing to cry about.”

So when my mother died March 15 this year and people suggested I must be taking it hard, as many did, I was reminded of His Holiness’s words. Not that she was the mother of anybody holy, but she did have a long and happy life, was devoted to the Dharma for her last thirty-five years, was ready to go, had a swift and relatively easy death, and from the moment it came had Lama Zopa Rinpoche doing po-wa and other prayers for her. In addition, many other lamas have been doing prayers and pujas, and at a recent teaching in New Delhi, which I was able to attend a few days after Mum’s funeral, His Holiness the Dalai Lama blessed her ashes. Also, her old and close friend, Ven. Konchog Dronma (Bonnie Rothenberg), who lives in Dharamsala, immediately organized many prayers and pujas at Gyüto and Gyümed Tantric Colleges and Kirti Gompa and many other merit-generating things as well. Finally, Lama Zopa Rinpoche had very kindly visited mother at her home in Melbourne in 2006 and felt that mentally, she was in a great place and had nothing to worry about.

I always (well, almost always) felt she was a perfect mother. Giving my brother Dorian and me top priority in her life, she always did what had to be done for our benefit and unconditionally supported our life choices, no matter how weird or unconventional they might have been, and often were. She frequently told me, “I just want you to be happy.”

My parents were Russian and came to Australia from Latvia in the mid-thirties. My father went into business and gave us all a comfortable middle-class life. My brother and I went to a top private school and, as was the norm, my mother didn’t have to work but was what used to be called a housewife. Not that she stayed in the house that much – her upper class life in Riga dictated that even in Melbourne she had hired help to do the cleaning, washing and so forth. She did, however, learn to cook.

My father died when I was in my last year of secondary school, and despite a total lack of experience, my mother took over his business in order to put both Dorian and me through medical school. After a few years of that she sold the business, bought a block of flats, and then learned to type so that she could team up with a blind friend translating scientific documents from Russian into English for the CSIRO. She did what had to be done. When after several years on the straight and narrow I started to venture beyond the conventional confines of medicine, she even watered the dope my friends and I grew in her backyard.

She loved to travel, so understood when, in 1972, I decided to take a four-year break from medicine to see the world. Accordingly, my girlfriend Marie (Yeshe Khadro) and I set off for the East and wandered around Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, Burma and India for about six months, eventually ending up in Nepal at the third Kopan meditation course. Up until that time I’d been sending her the perfunctory postcard: “Having a great time,” “The beaches are amazing,” “Wish you were here.” After the course I started sending her twenty-page evangelical raves about beginningless mind, the perfect human rebirth, impermanence and the imminence of death. She must have thought I’d gone troppo. Often I would finish my letters by saying that anyway, I couldn’t really explain what was going on at Kopan and if she wanted to know she’d have to come to find out for herself. So, at the age of sixty, she did. (Behind this may also have been the motivation to rescue me from the cult that had obviously brainwashed me.)

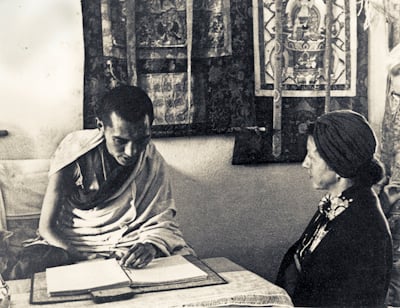

At the fourth course, March 1973, she met Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche and immediately made a strong connection with them. That was the last course held in the old gompa, and with 120 participants in that small space it was often quite humid. One day she fainted. We passed her out the side window and took her to where she was staying in Sister Max’s little brick house down from the gompa and laid her on the bed. I was like, “OK, take two aspirin and call me in the morning,” but then Lama appeared, sat beside her on the bed, and rubbed her back and recited mantras for a couple of hours. It really struck me how much more he cared about her than I, the son, did. A sobering moment.

At the fourth course, March 1973, she met Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche and immediately made a strong connection with them. That was the last course held in the old gompa, and with 120 participants in that small space it was often quite humid. One day she fainted. We passed her out the side window and took her to where she was staying in Sister Max’s little brick house down from the gompa and laid her on the bed. I was like, “OK, take two aspirin and call me in the morning,” but then Lama appeared, sat beside her on the bed, and rubbed her back and recited mantras for a couple of hours. It really struck me how much more he cared about her than I, the son, did. A sobering moment.

By the end of the course she still wasn’t convinced, but when she got back to Melbourne and thought about things she decided that Buddhism was definitely her path. As up to that point she’d been a card-carrying atheist and rabid scientific materialist, her ability to change a lifetime’s thinking was again testimony to her flexibility and openness of mind. When the Lamas came to Melbourne in 1974 and the next few years, they always stayed at her house. She was instrumental in the early development of Tara House (now Tara Institute) but eventually found a comfortable niche at the Buddhist Society of Victoria, where (again without any experience) she served as treasurer for fourteen years. Also, unlike most of us, as soon as she took refuge she immediately realized the cruelty, contradictions and hypocrisy inherent in a Buddhist’s eating meat and became a lifelong vegetarian. It took me more than thirty years to reach that point.

As ever, during this time, she supported me in every way. When I decided to drop out of medicine, stay in Nepal and become a monk, she accepted my choice and offered the $50 a month we all needed to live at Kopan in those days. Years later, when I was in London running Wisdom Publications and we needed money, she lent us tens of thousands of dollars. When in the mid-80s I decided to disrobe, she supported that decision as well. Actually, I had forgotten how much she helped me in my various Dharma jobs and how much I demanded of her until we were clearing out her house and I found a huge collection of letters I’d written to her over the years, most containing requests for her to do this or that, all of which she unstintingly did. I really felt embarrassed reading all these unreasonable demands. But she always did what had to be done.

Mother remained in amazingly good health, living alone at home and continuing to drive her increasingly battered car until she was ninety. Then, in 2004, after a minor tooth infection, she got dehydrated, passed out and lost enough brain function that she could no longer live unassisted. Up until then she had been wonderfully supported by Dorian and his ex-wife, Alison, a former director of Tara Institute and Mandala Books. Now they really stepped up to the plate to make sure Mum could remain at home with her beloved cat Kotik and not have to be institutionalized. They really took care of her and I am so grateful to them both, as their being there all these years has enabled me to be elsewhere, working for the FPMT in the various capacities I have. Also, Dorian, supported by his wife Cheryl, paid for Mum to have twenty-four-hour live-in home care so that she could remain in familiar surroundings until the end, an incredibly generous repayment of the kindness she had always shown us and something many others would not have chosen to do. I really thank him for that.

A couple of years ago Mum fell and broke her hip and it took her about eighteen months to fully recover. Then, on March 13, she broke the other one. After surgery the next day she seemed to be doing well but that night began to go downhill and passed away on the morning of the 15th.

Mother’s funeral on March 20 was more a celebration of her life. The service was beautifully conducted by Allys Andrews and the prayers and meditations led by Ven. Carolyn Lawler, both of Tara Institute. Most of Mother’s friends are, of course, dead but many of their children, my childhood friends, were there. Some of my friends from medical school also attended, as did many of her friends and colleagues from the FPMT and the BSV. Several of these people spoke about her life and it was a very warm occasion.

Some years ago Mum decided she would like her ashes to go into the Great Stupa of Universal Compassion being built in Bendigo, so that will be done. Also, Lama Zopa Rinpoche recommended making a set of large Twenty-one Taras statues in her memory and, since this is rather a lot for an individual to do, we are hoping to contribute to a set being made at Tushita Retreat Centre, Dharamsala. We are also hoping to make stupas for her at Root Institute, Chenrezig Institute and Land of Medicine Buddha and, to cover more bases, sprinkle some ashes in the Ganges!

May she once again come under the care of kind, compassionate lamas and quickly reach enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings.